Abstract

-

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) in human dental pulp after tooth bleaching with three in-office hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-based systems.

-

Methods

Forty pulps were collected from premolars scheduled for extraction and divided into four groups (n = 10): Control (no bleaching; basal NPY values); Pola Office (35% H2O2, 8 minutes); Opalescence Boost (40% H2O2, 20 minutes); and Zoom (25% H2O2 + cold blue light, 15 minutes). After extraction, pulps were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and processed. NPY levels were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data distribution was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction were applied (p < 0.05).

-

Results

NPY expression differed significantly among groups (p = 0.0097). The control group showed the lowest mean expression (0.026 ± 0.002 pmol/mg of pulp tissue), followed by Zoom (0.031 ± 0.005 pmol/mg), Pola Office (0.040 ± 0.004 pmol/mg), and Opalescence Boost, which exhibited the highest NPY expression (0.044 ± 0.004 pmol/mg). Post-hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference between the control and Opalescence Boost groups (p = 0.0122).

-

Conclusions

The increase in NPY expression—particularly with Opalescence Boost—indicates that in-office bleaching agents can elicit measurable neurobiological responses in pulp tissue after a single application. The significant difference between the control and Opalescence Boost groups suggests a possible H2O2 concentration- or formulation-dependent effect on pulpal neuropeptide activity, underscoring the need for further research on the biological impact of bleaching treatments.

-

Keywords: Dental pulp; Neurogenic inflammation; Neuropeptide Y; Tooth bleaching

INTRODUCTION

The human dental pulp is a highly specialized, vascularized, and innervated ectomesenchymal tissue, comprising an array of cell types, including immune cells, fibroblasts, and odontoblasts. The dental pulp can initiate a range of biological mechanisms to maintain homeostasis and pulp vitality in response to noxious stimuli, such as tooth-bleaching procedures [

1,

2].

Most tooth-bleaching products contain hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) as the active ingredient. When activated by chemicals or physical activators (i.e., enzymes, light, or heat), H

2O

2 dissociates into free radicals such as hydroxyl (OH), oxygen (O), and perhydroxyl (HO

2)—the most reactive free radical—responsible for the dentin’s bleaching effect [

3,

4].

H

2O

2-based tooth-bleaching systems such as Pola Office (35% H

2O

2; SDI, Bayswater, VIC, Australia), Opalescence Boost (40% H

2O

2; Ultradent Products, South Jordan, UT, USA), and Zoom (25% H

2O

2 + cold blue light, Zoom! Bleaching System; Discus Dental, Culver City, CA, USA) are some of the most popular in-office bleaching products. The free radicals released by these bleaching agents can diffuse through the enamel and dentin to reach the dental pulp, thus triggering a transitory reversible neurogenic inflammatory phenomenon that may manifest as dentinal hypersensitivity, with a prevalence of 15% to 78% of cases [

4–

7]. The extent of the inflammatory phenomenon depends on the H

2O

2 concentration, the free radicals’ interaction time with the substrates, and the activators’ molecular weight in each particular bleaching system [

8].

The inflammatory response that arises from the passage of free radicals into the pulp tissue is neurogenic in nature, as the nervous system governs the vascular and immune systems through the release of potent neuropeptides. Somatosensory nerve fiber stimulation causes the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P (SP), and neurokinin A (NKA), whereas sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers release neuropeptide Y (NPY) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), respectively [

9].

Neurogenic inflammation involves both myelinated Aδ and unmyelinated C fibers. Aδ and C fibers anastomose at the pulp tissue’s periphery, interacting with the vascular component to form the so-called Rashkow plexus, responsible for regulating blood flow through neuropeptide influence. The release of SP, CGRP, and NKA provokes vasodilation and drives the migration of immune cells

via chemotaxis, thus setting up an inflammatory response [

4,

10]. As a compensatory mechanism, NPY, a strong vasoconstrictor, and VIP, a regulatory vasodilator, are released to modulate the inflammatory process and preserve tissue homeostasis. Additionally, NPY and VIP promote pulp tissue repair by binding to specific cells, such as odontoblasts, fibroblasts, and immune cells [

11].

Neuropeptides are released in response to orthodromic and/or antidromic stimuli [

12,

13]. An orthodromic stimulus occurs under physiological conditions, such as temperature fluctuations or masticatory function. In these situations, A-delta fibers become activated, releasing NPY or VIP neuropeptides to sustain tissue homeostasis [

14,

15]. In contrast, H

2O

2 free radicals that reach the dental pulp generate an antidromic signal by exciting type C nerve endings, leading to the release of SP and CGRP, which triggers an inflammatory response that increases blood flow, intrapulpal pressure, and causes pulp volume expansion, which results in fluid flow into dentinal tubules, clinically translating into dentinal hypersensitivity [

4,

10]. As a negative control mechanism, the sympathetic system releases NPY to counteract the neurogenic inflammatory phenomena triggered by somatosensory neuropeptides. NPY-induced vasoconstriction reduces blood flow and intrapulpal pressure [

16,

17]. Likewise, NPY inhibits acetylcholine- and SP-induced vasodilation and amplifies the post-synaptic effects of other vasoconstrictors such as noradrenaline [

16]. NPY vasoconstriction modulates the vasodilatory impact of SP and CGRP, preventing pulp volume expansion and avoiding fluid movement in an antidromic direction into the dentinal tubules [

14]. Therefore, NPY functions as a defensive mechanism by regulating the inflammatory process in the dental pulp. Similarly, it has been proposed that the presence of NPY-1 receptors in fibroblasts, undifferentiated cells, and odontoblasts may be linked to pulp mineralization processes as a defense mechanism [

18,

19]. However, to date, the expression of NPY in dental pulp following different bleaching protocols is unknown. This information could be valuable for evaluating NPY behavior during routine clinical procedures and, as a result, aid clinicians’ decision-making to reduce pulp tissue injury.

In light of the preceding, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of different tooth-bleaching protocols (Pola Office, Opalescence Boost, and Zoom) on NPY expression in healthy human dental pulp, aiming at identifying potential control mechanisms of neurogenic pulp inflammation and dentinal hypersensitivity following tooth-bleaching procedures.

METHODS

A descriptive comparative clinical study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Colombian Ministry of Health regarding ethical considerations in research involving human tissues. The Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia (the members of the Medellin Sectional Bioethics Subcommittee) approved the study under resolution BIO407—Acta No.12, May 25, 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient who participated in the study. The study protocol was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT06606236).

The minimum sample size was calculated in advance as 10 per group using sampling software (G power ver. 3.1.9.2; Heinrich-Heine Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) based on previously published studies with a similar study population and methodological design from our group [

4,

17]. Forty dental pulps were collected from healthy non-smoking human donors aged 18 to 27 years who underwent premolar extractions for orthodontic purposes. All premolars were caries and restoration-free, with complete root development, confirmed both visually and radiographically, with normal response to sensitivity testing, and no evidence of periodontal disease, traumatic occlusion, or previous orthodontic force application. Teeth with similar features were selected to ensure the validity and reliability of the results, while limiting bias and any confounding factors.

Samples were randomly assigned (with the aid of a randomizer tool [random.org]) into four groups containing 10 healthy premolars each (without discriminating between maxillary and mandibular premolars): (i) control group: the teeth were not exposed to dental bleaching agents (healthy pulps with normal/basal NPY values); (ii) Pola Office group: application of Pola Office (35% H2O2) for 8 minutes (single application), (iii) Opalescent Boost group: application of Opalescent Boost (40% H2O2) for 20 minutes (single application), and (iv) Zoom group: application of Zoom! (25% H2O2 + cold blue light) for 15 minutes (single application). A high-intensity LED light source emitting in the visible blue spectrum (400–505 nm) was employed, delivering an average irradiance of 150–200 mW/cm2. This corresponds to a total energy density of approximately 72–96 J/cm2. According to the manufacturer, this energy range ensures efficient activation of the photoinitiators contained in the bleaching gel while minimizing thermal effects on dental and pulpal tissues. The manufacturer’s instructions were strictly followed, but due to the nature of the research, a single application was performed in the experimental groups.

A preliminary sensitivity test was conducted to assess the normal state of the pulp. This involved using a pulp tester to evaluate the pulp’s response to an electrical stimulus. Likewise, a cold test was performed using Endo Ice (1,1,1,2 tetrafluoroethane; Hygenic Corp, Akron, OH, USA) to confirm the results further. These tests collectively verified that the sensitivity of the premolars was within normal limits.

Clinical procedures and sample collection

Following tooth bleaching, teeth were anaesthetized immediately with 3% mepivacaine without vasoconstrictor infiltration injection for maxillary premolars and inferior alveolar nerve block injection for mandibular premolars. Ten minutes later, the teeth were extracted using conventional methods, employing a supraosseous luxation and extraction technique. The extraction process took no more than 5 minutes. For the control group, extraction was also performed 10 minutes after the anesthetic application. After extraction, all teeth were rinsed with 5.25% sodium hypochlorite to remove any remaining periodontal ligament that could contaminate the pulp sample. The teeth were sectioned using a Zekrya bur (Dentsply, Tulsa, OK, USA) in a high-speed handpiece, irrigated with a saline solution. Pulp tissue was collected using a sterile endodontic excavator, deposited on an Eppendorf tube with 1 mL 4% paraformaldehyde, and stored at 70°C until examination [

17]. Tubes were identified with a code to blind the operator who would process the samples.

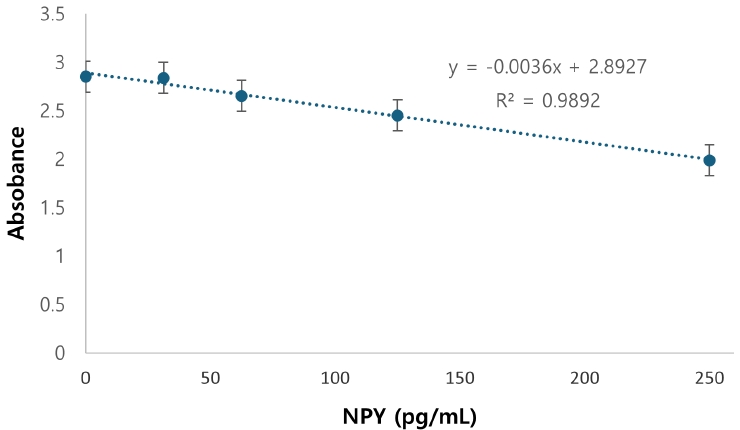

Dental pulp samples were defrosted without thermal shock, dried on a filter, and weighed on an analytical balance. NPY was extracted by adding 150 mL of 0.5 mol/L of acetic acid and double boiling in a thermostat bath for 30 minutes [

13]. NPY expression was determined by a specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for NPY.

A volume of 50 µL from each standard, blank, and sample was added to the corresponding wells. All samples and standards were duplicated. The sample dilution was established by preliminary experiments. A 50 µL/well working solution with biotinylated antibody was added. The plate was covered with sealing film and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C. After decanting the solution, each well was dispensed with 350 µL of wash buffer (soaked for 1 minute). Plates were washed three times and gently blotted before 100 µL of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated working solution was added to each well. The plate was covered with a new sealing film and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. After washing plates five times as previously described, the substrate was added (50 μL/well). The plate was incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. The plate was protected from light by wrapping it in aluminum foil, which caused a color change. A volume of 50 µL/well of stop solution was added in the same order as the substrate solution was previously added. The optical density (OD) of each well was determined using a microplate reader at 450 nm [

20].

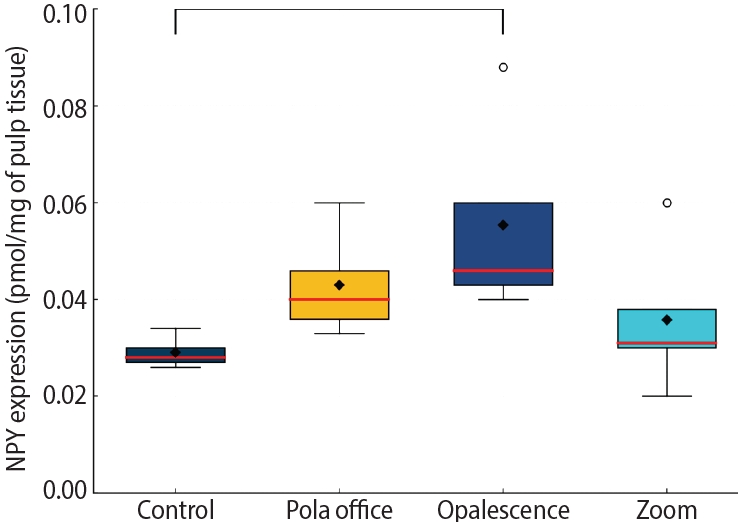

A calibration curve from 31.25 to 2,000 pg/mL was prepared in duplicate according to the kit instructions (Human Neuropeptide Y ELISA Kit, E-EL-H1893; Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA) (

Appendix 1). The kit’s sensitivity is 18.75 pg/mL. The NPY concentration (pg/mL) was obtained by interpolating the OD results with the sample supernatants (pre-weighed tissues, macerated in phosphate-buffered saline [pH, 7.4; 100 mM] and centrifuged at 6,000

g at 4°C for 15 minutes). The amount of NPY/pg was then divided by the molecular weight of the neuropeptide and the amount of sample in mg to get the NPY concentration in pmol of the peptide/mg of fresh tissue.

Values were obtained in duplicate from each sample (20 per group). For each of the bleaching techniques analyzed, mean and standard error, as well as minimum and maximum values for NPY, expressed in pmol/mg of pulp tissue, were calculated. A Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to determine the distribution of the dataset. An one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed to evaluate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Since significant differences were found, the Tukey post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction was applied at a significance level of p < 0.05.

RESULTS

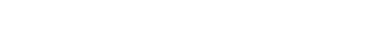

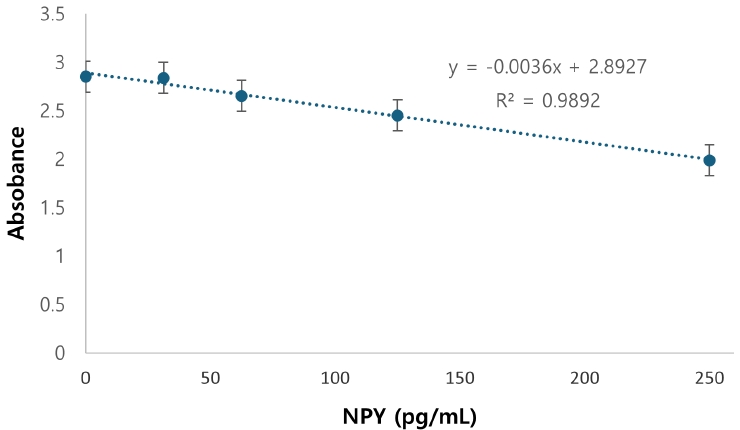

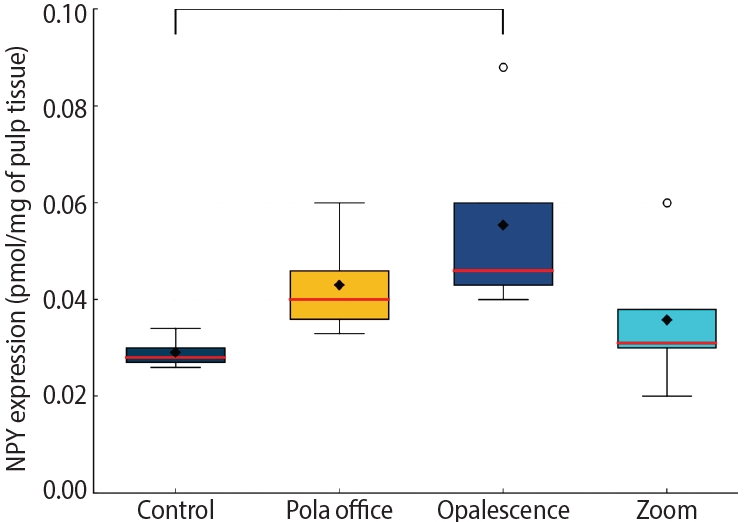

Table 1 outlines the NPY expression in pmol/mg of pulp tissue, revealing that the lowest expression was observed in the control group, followed by the Zoom! Pola Office and Opalescence Boost systems, respectively (one-way ANOVA: single factor

p = 0.0097).

Table 2 displays Tukey

post-hoc comparisons, which demonstrate that the only statistically significant difference was observed between the control and Opalescence Boost groups (

p = 0.012). All other pairwise comparisons showed no statistically significant differences (

p ≥ 0.05).

Figure 1 displays NPY expression levels in dental pulp tissue across the four bleaching protocols. Box plots represent NPY concentrations (pmol/mg) in control, Pola Office, Opalescence Boost, and Zoom groups. Red lines indicate medians, and black diamonds denote means. A significant increase in NPY was found in the Opalescence group compared to the control (

p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Tooth bleaching has been shown to elicit a neurogenic, reversible pulpal inflammatory response, as free radicals dissociated from H

2O

2 diffuse through enamel and dentin into the pulp tissue. The magnitude of the neurogenic inflammatory response is strongly related to the bleaching system’s H

2O

2 concentration, exposure time, and activation mode [

1,

3-

6,

9].

H

2O

2 free radicals activate somatosensory nerve terminals in the Rashkow plexus [

11], leading to the up-regulated expression of SP, CGRP, and NKA from Aδ and C fibers, resulting in transient pulp inflammation. When the inflammatory phenomenon is not properly regulated, it can lead to the apoptosis of odontoblasts and fibroblasts, resulting in premature pulp aging, which jeopardizes the pulp tissue’s protective mechanisms and homeostasis [

5,

9,

21,

22]. Furthermore, the inflammatory phenomena caused by bleaching procedures trigger antidromic stimulation due to increased blood flow and intrapulpal pressure, resulting in an increase in dental pulp volume and enhanced fluid flow into the dentinal tubules, which is clinically described as post-bleaching dentinal hypersensitivity [

23].

NPY is released by exocytosis from sympathetic Aδ and C fibers as a compensatory anti-inflammatory mechanism. NPY binds to target cells

via the NPY-1 receptor, which is expressed in fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, odontoblasts, and undifferentiated dental pulp cells. It competes and antagonizes pro-inflammatory somatosensory neuropeptides, such as SP, CGRP, and NKA [

11,

15,

16,

24]. NPY exerts a vasoconstrictor effect, aided by norepinephrine at the post-synaptic level, thus counteracting the vasodilation generated by SP and CGRP [

17]. Furthermore, NPY promotes pulp tissue repair by attaching to its receptor NPY-1 in target cells, such as macrophages responsible for degrading H

2O

2 free radicals [

25]. Likewise, NPY drives endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis, fibroblasts to renew and repair the extracellular matrix, and dental pulp stem cells to undergo odontoblastic differentiation, with the ultimate aim of producing tertiary dentin even up to 21 days following exposure to H

2O

2 agents [

15,

22,

26]. All of these regulatory and reparative mechanisms lead to a decline in the inflammatory reaction a few days post-tooth bleaching, which in turn results in the control of dentinal hypersensitivity by restricting fluid flow into the dentinal tubules [

23]. Additionally, when dental pulp is exposed to H

2O

2 free radicals, the up-regulated expression of dismutase and catalase, which enzymatically break down the perhydroxyl ion, provides a protective impact on the pulp cells and preserves pulp vitality over time [

11,

13].

Three different in-office tooth-bleaching systems—Pola Office, Opalescence Boost, and Zoom—were used in this study to quantify NPY expression in human dental pulp following tooth-bleaching procedures. We rigorously followed the manufacturer’s instructions, as the detrimental impacts of H

2O

2 on pulp tissue are proportional to the concentration, application time, and activation method [

27]. Depending on NPY expression, it may be feasible to infer the magnitude of the neurogenic inflammatory phenomenon following tooth-bleaching procedures and how NPY modulates the inflammatory process [

23].

The ELISA test was performed to quantify NPY expression. It has been established that the ELISA test is sensitive enough to quantify neuropeptides in pmol/mg of pulp weight, the most generally used unit of measurement for neuropeptide expression in freshly extracted human dental pulp [

28]. Considering the lack of previous research on NPY expression following tooth bleaching, a direct comparison was conducted between basal levels (pre-bleaching) and pulp inflammation (post-bleaching) in healthy premolars requiring extraction for orthodontic reasons [

17]. Differences found between groups validate the sensitivity of the ELISA test.

All groups received 3% mepivacaine without a vasoconstrictor as a local anesthetic to prevent alpha-adrenergic agonists from minimizing neuropeptide expression. To allow NPY expression, a 10-minute interval was set aside following the removal of the bleaching agent [

28]. Teeth were extracted using a supraosseous luxation and extraction technique, which should not take longer than 5 minutes to prevent endogenous endopeptidases from degrading the neuropeptide and to quantify the NPY expression linked to the bleaching procedure rather than the dental extraction [

4,

17].

The control group exhibited a mean NPY expression of 0.026 pmol/mg of pulp tissue, demonstrating that NPY is present in human dental pulp under physiological conditions. These values are consistent with previous studies that employed radioimmunoassay to assess NPY expression [

17]. The Zoom system group (25% H

2O

2) achieved an average NPY expression of 0.031 pmol/mg of pulp tissue after 15 minutes of application and activation with a cold blue light. There was no significant difference (

p ≥ 0.05) compared to the control group’s reference values. These results can be attributed to the fact that the Zoom bleaching system utilizes the lowest concentration of bleaching agents evaluated in this study, and its activation method involved a cold light lamp. Notably, the findings from this study differ from those of previous research, which assessed SP expression in human dental pulp in response to 25% Zoom bleaching with hot light activation. The Zoom system was found to elicit the highest SP expression, most likely due to the increased release of H

2O

2 free radicals by the activation source [

29]. Such results confirm that the activation method of the bleaching agent impacts the expression of neuropeptides in the dental pulp and, therefore, the severity of neurogenic inflammation [

4,

30].

Similarly, NPY expression is directly proportional to the amount of H2O2 free radicals that enter the pulp tissue. The Pola Office system group (35% H2O2) with 8 minutes of application and the Opalescence Boost system group (40% H2O2) with 20 minutes of application displayed an average expression of 0.040 pmol/mg of pulp tissue and 0.044 pmol/mg of pulp tissue, respectively. No significant difference (p ≥ 0.05) was observed between these two groups.

Opalescence Boost was the only group that showed statistically significant differences (

p ˂ 0.05) compared to the control group, implying that NPY expression is directly proportional to the concentration of the bleaching agent. Furthermore, it can be inferred that the Pola Office, followed by the Opalescence Boost system group, triggers a more intense inflammatory phenomenon, as evidenced by higher NPY expression, which attempts to preserve pulp tissue homeostasis [

4,

9].

NPY is released to modulate neurogenic inflammation mediated by somatosensory neuropeptides, thereby making pulp inflammation reversible [

14,

23,

31]. NPY promotes protective vasoconstriction, thereby decreasing blood flow, intrapulpal pressure, and inflammatory cell chemotaxis, while also inhibiting neural activity by blocking SP and CGRP, thereby modulating the antidromic stimuli of fluid flow into dentinal tubules, which minimizes post-bleaching dentinal hypersensitivity [

23,

31]. However, as a long-term adverse effect, NPY release may result in premature aging of the dental pulp by eliciting pro-angiogenic defensive reactions [

1,

28]. It has been proposed that NPY binding to its specific receptor, NPY-1, in fibroblasts, undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, and odontoblasts may be linked to pulp mineralization processes as a defense mechanism. Apoptosis of these cells has also been observed when the effect of free radicals generated by dental bleaching surpasses the pulp tissue’s tolerance [

9,

11,

32]. When the aggression of free radicals from tooth bleaching systems exceeds the tolerance of the pulp tissue’s defense mechanisms, as a result of using high concentrations of H

2O

2 and improper application times, irreversible pulpitis associated with the overexpression of NKA, SP, and CGRP may develop [

4]. This leads to the destruction of immature odontoblasts and the DNA of undifferentiated cells [

5,

9,

22], degeneration of pulp fibroblasts, and irreversible damage to immune cells, such as macrophages, which prevents pulp tissue from being repaired [

26,

32]. In this scenario, neither parasympathetic nor sympathetic neuropeptides, such as VIP and NPY, can regulate the inflammatory response.

This biological response suggests that bleaching protocols employing agents with higher irritative potential—particularly those containing high concentrations of peroxides or relying on unnecessary light activation—may contribute to premature pulpal aging [

1,

28]. Consequently, clinicians should carefully consider the selection of bleaching protocols, prioritizing the use of lower-concentration peroxide agents, minimizing the number of sessions, and avoiding light sources in products that do not require photoactivation. These findings underscore the importance of strictly adhering to the manufacturer’s instructions, as deviations from the recommended protocol may increase the risk of pulpal damage without providing significant aesthetic benefits.

In light of these findings, future research should incorporate clinical sensitivity assessments alongside NPY quantification; investigate NPY responses to novel bleaching formulations, including nanoparticle-enhanced systems; examine the longitudinal effects of multiple bleaching sessions; and explore the spatial distribution patterns of NPY and NPY-1 receptors within the pulp tissue.

One of the main limitations of our study is the design of the treatment protocol. Although the single-application approach ensured methodological consistency and minimized variability, it does not fully represent routine clinical practice, where multiple bleaching sessions are commonly performed. Evidence from studies evaluating novel whitening agents suggests that cumulative exposure over successive applications may produce different biological effects on dental tissues. Therefore, a longitudinal investigation assessing NPY expression following multiple bleaching sessions would yield findings that are more representative of real-world clinical scenarios [

33].

Despite the limitations of this in vivo study, it can be suggested that NPY expression correlates with the concentration of the bleaching agent and the intensity of the inflammatory response, thereby modulating the pulp’s reactions to neurogenic pulp inflammation induced by tooth-bleaching procedures. This study found the highest NPY expression in Opalescence Boost, followed by Pola Office and Zoom. Further research on this topic should focus on correlating NPY expression with dentinal hypersensitivity levels following tooth bleaching protocols, with the goal of identifying mechanisms that contribute to dentinal hypersensitivity oversight.

CONCLUSIONS

The highest NPY expression values were found in Opalescence Boost, followed by Pola Office and Zoom. The significant increase in NPY expression, particularly in the Opalescence Boost group, demonstrates that even a single application of hydrogen peroxide-based bleaching agents can activate neurogenic signaling pathways within the dental pulp. This finding reveals a biologically active response at the molecular level, suggesting that tooth whitening procedures may induce early pulpal stress. The significant difference observed between the control and Opalescence Boost groups suggests a potential H2O2 concentration- or formulation-dependent effect on pulpal neuropeptide activity, highlighting the need for further longitudinal studies on the biological impact of bleaching treatments.

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Caviedes-Bucheli J; Data curation: Muñoz-Alvear HD, Gomez-Sosa JF, Güiza–Cristancho E; Formal analysis: Roberto Munoz H, Ríos-Osorio N; Investigation: Pérez-Villota M, Aucú-Miño K, Escobar-Mafla D, Diaz-Barrera L; Supervision: Caviedes-Bucheli J, Muñoz-Alvear HD; Validation: Ríos-Osorio N, Roberto Munoz H; Visualization: Ríos-Osorio N; Writing - original draft: Caviedes-Bucheli J, Ríos-Osorio N; Writing - review & editing: Ríos-Osorio N. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Figure 1.Boxplot of the neuropeptide Y (NPY) expression in dental pulp following different bleaching techniques. Pola Office: SDI, Bayswater, VIC, Australia; Opalescence Boost: Ultradent Products, South Jordan, UT, USA; Zoom: Discus Dental, Culver City, CA, USA.

Table 1.Expression of neuropeptide Y in dental pulps after different bleaching techniques

|

Group |

n

|

Mean |

Standard error |

Median |

Maximum |

Minimum |

95% CI |

IQR |

p-value (SW) |

Single factor p-value (one-way ANOVA) |

|

Control |

10 |

0.026 |

0.002 |

0.024 |

0.047 |

0.012 |

0.0223–0.0302 |

0.012 |

0.169 |

0.0097 |

|

Pola Office |

10 |

0.040 |

0.004 |

0.034 |

0.075 |

0.011 |

0.0314–0.0484 |

0.030 |

0.350 |

|

|

Opalescence |

10 |

0.044 |

0.004 |

0.037 |

0.086 |

0.019 |

0.0355–0.0526 |

0.020 |

0.091 |

|

|

Zoom |

10 |

0.031 |

0.005 |

0.027 |

0.068 |

0.006 |

0.0222–0.0406 |

0.033 |

0.200 |

|

Table 2.Tukey post hoc comparisons

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Mean |

Standard error |

p-value |

|

Control |

Pola Office |

0.014 |

0.004 |

0.0817 |

|

Control |

Opalescence |

0.018 |

0.004 |

0.0122 |

|

Control |

Zoom |

0.005 |

0.004 |

0.7981 |

|

Pola Office |

Opalescence |

0.004 |

0.004 |

0.8844 |

|

Pola Office |

Zoom |

0.009 |

0.004 |

0.4377 |

|

Opalescence |

Zoom |

0.013 |

0.004 |

0.1221 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Gomez-Sosa JF, Azuero-Holguin MM, Ormeño-Gomez M, Pinto-Pascual V, Munoz HR. Angiogenic mechanisms of human dental pulp and their relationship with substance P expression in response to occlusal trauma. Int Endod J 2017;50:339-351.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Pohl S, Akamp T, Smeda M, Uderhardt S, Besold D, Krastl G, et al. Understanding dental pulp inflammation: from signaling to structure. Front Immunol 2024;15:1474466.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Sun L, Liang S, Sa Y, Wang Z, Ma X, Jiang T, et al. Surface alteration of human tooth enamel subjected to acidic and neutral 30% hydrogen peroxide. J Dent 2011;39:686-692.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Ariza-García G, Restrepo-Méndez S, Ríos-Osorio N, Lombana N, Muñoz HR. The effect of tooth bleaching on substance P expression in human dental pulp. J Endod 2008;34:1462-1465.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Basting RT, Amaral FL, França FM, Flório FM. Clinical comparative study of the effectiveness of and tooth sensitivity to 10% and 20% carbamide peroxide home-use and 35% and 38% hydrogen peroxide in-office bleaching materials containing desensitizing agents. Oper Dent 2012;37:464-473.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 6. Minoux M, Serfaty R. Vital tooth bleaching: biologic adverse effects: a review. Quintessence Int 2008;39:645-659.PubMed

- 7. Meireles SS, Goettems ML, Dantas RV, Bona ÁD, Santos IS, Demarco FF. Changes in oral health related quality of life after dental bleaching in a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Dent 2014;42:114-121.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Bharti R, Wadhwani K. Spectrophotometric evaluation of peroxide penetration into the pulp chamber from whitening strips and gel: an in vitro study. J Conserv Dent 2013;16:131-134.ArticlePMC

- 9. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Muñoz HR, Azuero-Holguín MM, Ulate E. Neuropeptides in dental pulp: the silent protagonists. J Endod 2008;34:773-788.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Lopez-Moncayo LF, Muñoz-Alvear HD, Gomez-Sosa JF, Diaz-Barrera LE, Curtidor H, et al. Expression of substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide and vascular endothelial growth factor in human dental pulp under different clinical stimuli. BMC Oral Health 2021;21:152.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Kina JF, Huck C, Riehl H, Martinez TC, Sacono NT, Ribeiro AP, et al. Response of human pulps after professionally applied vital tooth bleaching. Int Endod J 2010;43:572-580.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Olgart L, Edwall L, Fried K. Cat dental pulp after denervation and subsequent re-innervation: changes in blood-flow regulation and distribution of neuropeptide-, GAP-43- and low-affinity neurotrophin receptor-like immunoreactivity. Brain Res 1993;625:109-119.Article

- 13. Kawashima N, Okiji T. Characteristics of inflammatory mediators in dental pulp inflammation and the potential for their control. Front Dent Med 2024;5:1426887.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Kim S. Neurovascular interactions in the dental pulp in health and inflammation. J Endod 1990;16:48-53.ArticlePubMed

- 15. El-Karim I, Lundy FT, Linden GJ, Lamey PJ. Extraction and radioimmunoassay quantitation of neuropeptide Y (NPY) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) from human dental pulp tissue. Arch Oral Biol 2003;48:249-254.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Lundy FT, Linden GJ. Neuropeptides and neurogenic mechanisms in oral and periodontal inflammation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2004;15:82-98.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Lombana N, Azuero-Holguín MM, Munoz HR. Quantification of neuropeptides (calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, neurokinin A, neuropeptide Y and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide) expressed in healthy and inflamed human dental pulp. Int Endod J 2006;39:394-400.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Killough SA, Lundy FT, Irwin CR. Dental pulp fibroblasts express neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor but not neuropeptide Y. Int Endod J 2010;43:835-842.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Rethnam S, Raju B, Fristad I, Berggreen E, Heyeraas KJ. Differential expression of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors during pulpal inflammation. Int Endod J 2010;43:492-498.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Nurhapsari A, Cilmiaty R, Prayitno A, Purwanto B, Soetrisno S. The role of Asiatic acid in preventing dental pulp inflammation: an in-vivo study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2023;15:109-119.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 21. Sharma H, Sharma DS. Detection of hydroxyl and perhydroxyl radical generation from bleaching agents with nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2017;41:126-134.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Reis-Prado AH, Grossi IR, Chaves HG, André CB, Morgan LF, Briso AL, et al. Influence of hydrogen peroxide on mineralization in dental pulp cells: a systematic review. Front Dent Med 2021;2:689537.Article

- 23. Pashley DH. How can sensitive dentine become hypersensitive and can it be reversed? J Dent 2013;41 Suppl 4:S49-S55.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Mehboob R, Hassan S, Gilani SA, Hassan A, Tanvir I, Waseem H, et al. Enhanced neurokinin-1 receptor expression is associated with human dental pulp inflammation and pain severity. Biomed Res Int 2021;2021:5593520.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 25. Galler KM, Weber M, Korkmaz Y, Widbiller M, Feuerer M. Inflammatory response mechanisms of the dentine-pulp complex and the periapical tissues. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22.Article

- 26. Zhan C, Huang M, Zeng J, Chen T, Lu Y, Chen J, et al. Irritation of dental sensory nerves promotes the occurrence of pulp calcification. J Endod 2023;49:402-409.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Donato MV, Dos Reis-Prado AH, Abreu LG, de Arantes LC, Goto J, Chaves HGDS, et al. Influence of dental bleaching on the pulp tissue: a systematic review of in vivo studies. Int Endod J 2024;57:630-654.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Lopez-Moncayo LF, Muñoz-Alvear HD, Hernandez-Acosta F, Pantoja-Mora M, Rodriguez-Guerrero AS, et al. Expression of early angiogenesis indicators in mature versus immature teeth. BMC Oral Health 2020;20:324.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 29. Gibbs JL, Hargreaves KM. Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor effects on pulpal nociceptors. J Dent Res 2008;87:948-952.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 30. Buchalla W, Attin T. External bleaching therapy with activation by heat, light or laser--a systematic review. Dent Mater 2007;23:586-596.ArticlePubMed

- 31. He LB, Shao MY, Tan K, Xu X, Li JY. The effects of light on bleaching and tooth sensitivity during in-office vital bleaching: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2012;40:644-653.ArticlePubMed

- 32. Fernandes AM, Vilela PG, Valera MC, Bolay C, Hiller KA, Schweikl H, et al. Effect of bleaching agent extracts on murine macrophages. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22:1771-1781.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 33. Mansoor A, Mansoor E, Hussain K, Khan S. Clinical efficacy of novel biogenically fabricated titania nanoparticles enriched mouth wash in treating the tooth dentine hypersensitivity: a randomized clinical trial. Pak J Med Sci 2025;41:1743-1748.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

Appendix

Appendix 1.

- Calibration curve for neuropeptide Y (NPY) quantification by competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

, Néstor Ríos-Osorio2,3

, Néstor Ríos-Osorio2,3 , Mario Pérez-Villota4

, Mario Pérez-Villota4 , Karolina Aucú-Miño4

, Karolina Aucú-Miño4 , Diana Escobar-Mafla4

, Diana Escobar-Mafla4 , Hernán Darío Muñoz-Alvear4

, Hernán Darío Muñoz-Alvear4 , José Francisco Gomez-Sosa5

, José Francisco Gomez-Sosa5 , Luis Diaz-Barrera6

, Luis Diaz-Barrera6 , Edgar Güiza – Cristancho4

, Edgar Güiza – Cristancho4 , Hugo Roberto Munoz7

, Hugo Roberto Munoz7

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite