Abstract

-

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review is to compare the effectiveness of advanced platelet concentrates as regenerative endodontic therapeutic alternatives to blood clot (BC) revascularization in immature permanent necrotic teeth.

-

Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing regenerative endodontic therapies using platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), or platelet pellet (PP) with the BC revascularization approach in immature permanent necrotic teeth were systematically searched in PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science until May 2025. Data was extracted and analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. A meta-analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS software (version 29.0), with success rates expressed as risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

-

Results

The initial search yielded 4,917 studies. After removing duplicates and applying eligibility criteria, 15 RCTs were included. Meta-analysis indicated no significant difference in the risk ratio (RR), as the BC method has similar success rates with PRP (10 studies; RR = 1.01; 95% CI, 0.94–1.09; p = 0.76) and PRF (8 studies; RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89–1.08; p = 0.65) at 12 months. The primary outcomes evaluated were based on clinical and radiographic success.

-

Conclusions

Current evidence suggests PRP, PRF, and BC are all effective in treating immature permanent necrotic teeth with similar success rates. However, further research is needed to assess long-term outcomes.

-

Keywords: Apexification; Platelet-rich fibrin; Platelet-rich plasma; Regenerative endodontics

INTRODUCTION

In regenerative endodontics, biologically driven methods are used to restore the pulp-dentin complex, dentin, and root structures of the treated teeth [

1]. These treatment modalities utilize stem cells, biomaterial scaffolds, and signaling molecules to promote healing, resolve symptoms, and support further root maturation leading to increased dentinal thickness, root length, and structural strength, reduced risk of fractures, and reduced tooth sensitivity. In clinical endodontics, regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) are now considered the treatment of choice for immature permanent teeth with pulp necrosis [

1–

5].

In biological terms, REPs aim to replace inflamed or necrotic pulp tissue with newly formed, pulp-like tissue that ideally includes a peripheral layer of odontoblast-like cells, mimicking the structure of healthy pulp. Kim

et al. [

4] suggest that these procedures aim to resolve clinical signs and symptoms, promote root maturation, and restore neurogenesis. These therapeutic outcomes may be achieved through

cell homing, a process in which endogenous stem or progenitor cells migrate to the site of injury through passive blood flow from the periapical tissues, leading to the formation of a blood clot (BC) that acts as a natural scaffold [

4,

6,

7]. These regenerative stimuli can be further enhanced by platelet-derived biomaterials (platelet concentrates), such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), and platelet pellet (PP), which release growth factors that induce cell recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation.

In endodontics, platelet concentrates serve as scaffolds that support revascularization and tissue regeneration within the root canal system [

8]. These techniques evolved from the traditional BC method, long regarded as the gold standard in regenerative endodontics. In this approach, bleeding is intentionally induced from the periapical tissues to create an intracanal BC. This clot functions as a natural scaffold, attracting and delivering growth factors and progenitor cells from the apical papilla into the canal space, thereby facilitating tissue regeneration [

9]. It was not until 2016 that renowned organizations such as the American Association of Endodontists and the European Society of Endodontology recognized the significance of regenerative endodontic treatments (RETs), with the former proposing a standardized protocol for REPs, which included the use of scaffolds such as PRP or PRF, and the latter publishing a position statement on revitalization procedures [

10,

11].

The objective of the present study is to compare the clinical effectiveness of platelet concentrates as a therapeutic alternative to conventional BC revascularization for the treatment of immature permanent necrotic teeth with at least 12 months of follow-up time through a systematic review approach. According to the null hypothesis, there is no significant difference in the clinical success rates between platelet concentrates and conventional BC approaches for the treatment of immature permanent necrotic teeth over a minimum follow-up period of 12 months.

METHODS

Protocol and registration

A comprehensive protocol of the present systematic review has been created and registered with the PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; registration number, CRD420251057926). The systematic review is being conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [

12].

An extensive literature search was conducted across multiple electronic databases, including the Web of Science by Clarivate Analytics (All Collections and Core Collection), the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE PubMed, and Elsevier Scopus. A combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms was employed to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the use of PRP, PRF, or PP in REPs for immature necrotic teeth. The search encompassed all available records from inception through May 2, 2025. A manual search was also conducted by screening the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The search strategy for each database is presented in

Table 1.

1. PICO framework

Population: Immature necrotic permanent teeth.

Intervention: REP using platelet concentrates.

Comparison: REP by inducing the formation of a BC as a scaffold.

Outcomes: Radiographic assessment and clinical examination.

Study: RCTs with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months.

2. Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were applied for study inclusion:

• RCTs published in the English language.

• Studies comparing the clinical success rates of PRP, PRF, or PP with the conventional BC technique in REPs for immature necrotic permanent teeth.

• Studies reporting a minimum follow-up period of 12 months posttreatment.

3. Exclusion criteria

Studies that met any of the criteria listed below were excluded:

• Retrospective, preclinical animal studies, in vitro investigations, case control, non-randomized studies, case series, case reports, book chapters, meta-analyses, narrative, systematic, and scoping reviews.

• Studies for which the full-text version was unavailable after two unsuccessful attempts to contact the corresponding author via email.

• Studies with a follow-up period of less than 12 months.

• Studies involving primary or fully mature permanent teeth.

• Studies without a control group treated with the BC technique.

• Studies that did not report data in a comparative format suitable for analysis.

Data collection

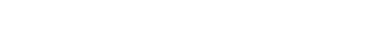

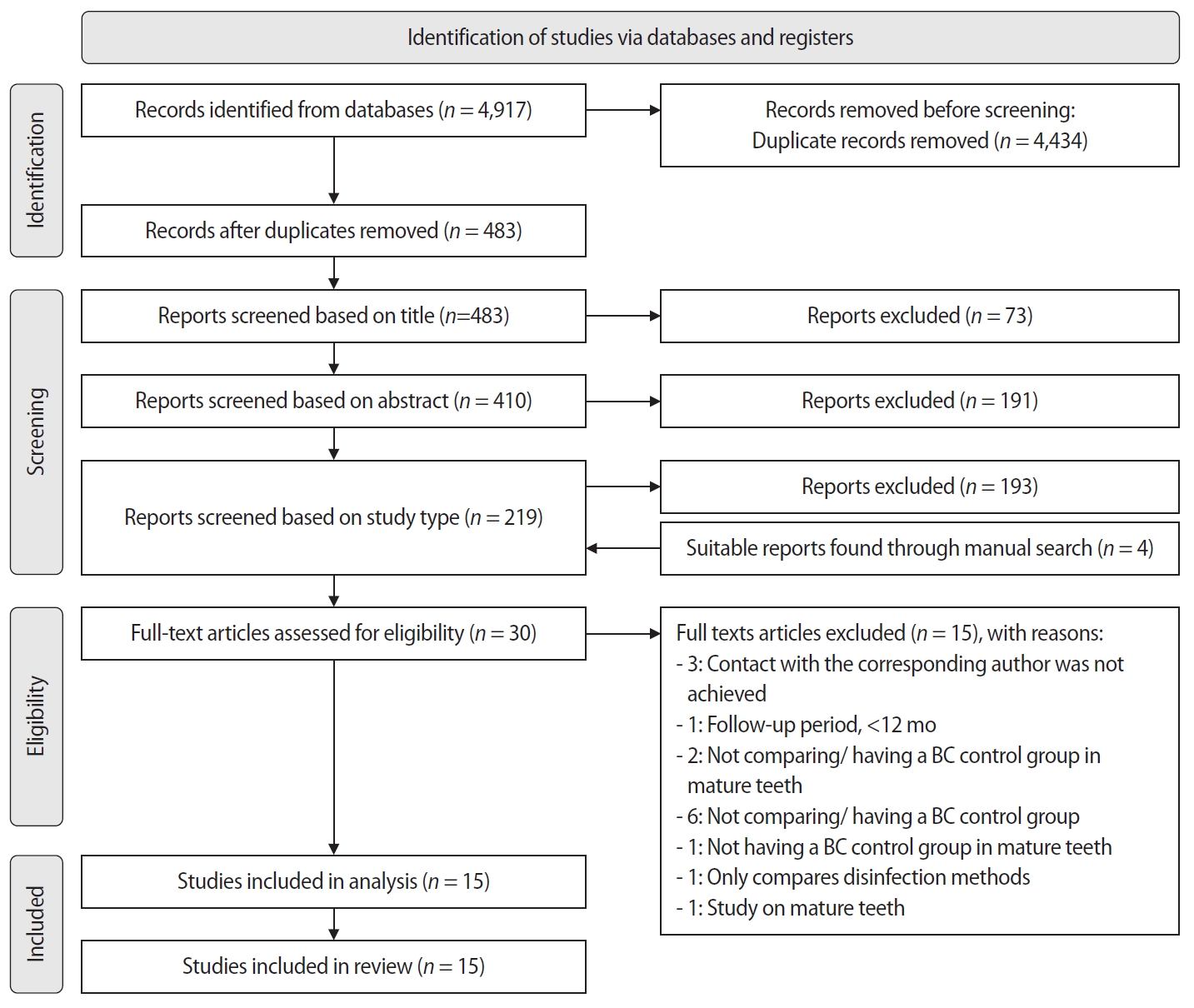

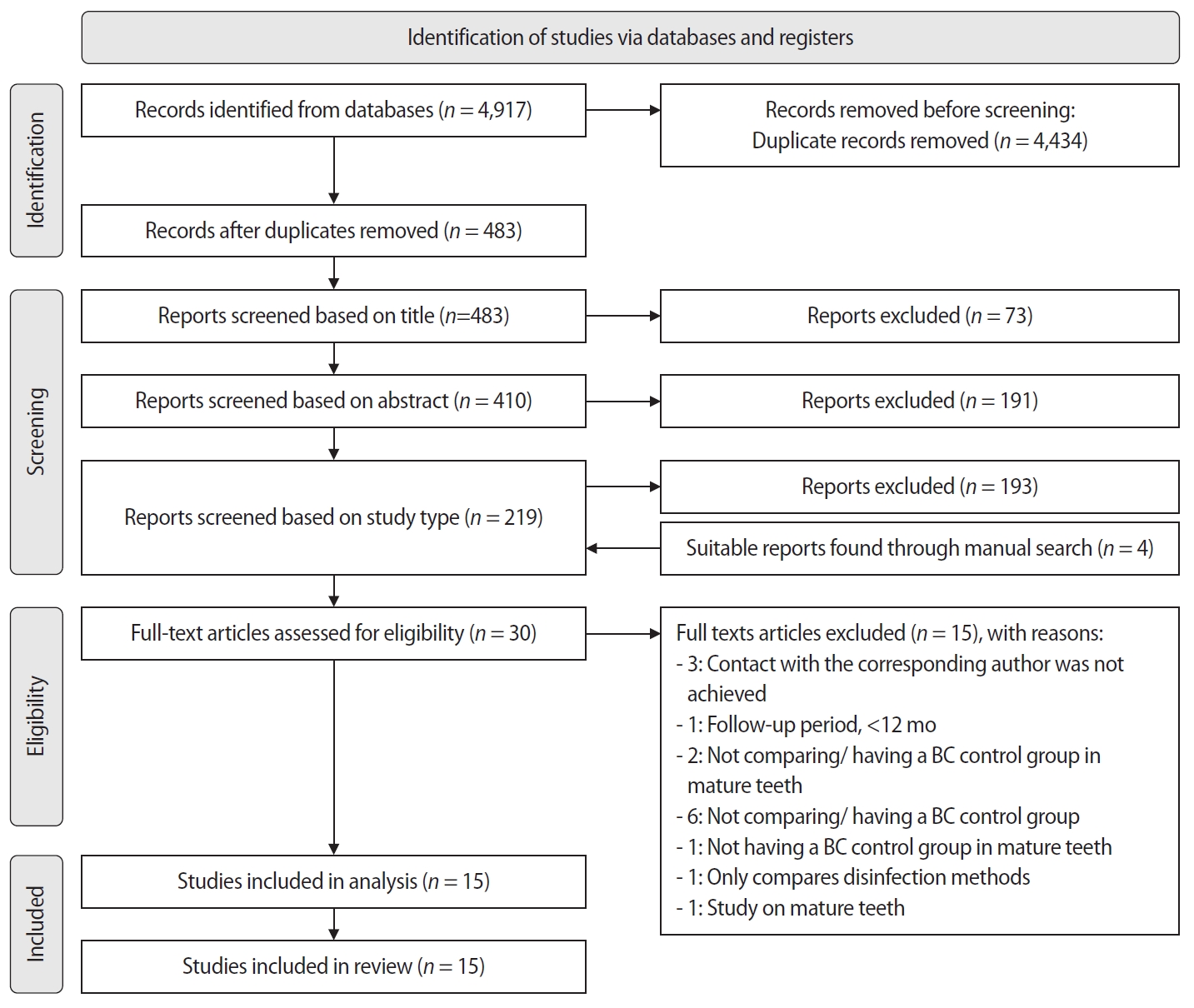

The titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles were independently screened by three reviewers (DT, NT, AT). During the selection process, any disputes were resolved through discussion and, when necessary, consultation with a fourth reviewer (KK). This process was consistently applied at each stage of screening. Subsequently, full-text articles of potentially eligible studies, including those identified through manual searching, were assessed for inclusion by the same three reviewers (DT, NT, AT), with final confirmation by the fourth reviewer (KK). The study selection process is demonstrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1). The list of excluded full-text articles, along with the reasons for their exclusion, is provided in

Supplementary Table 1.

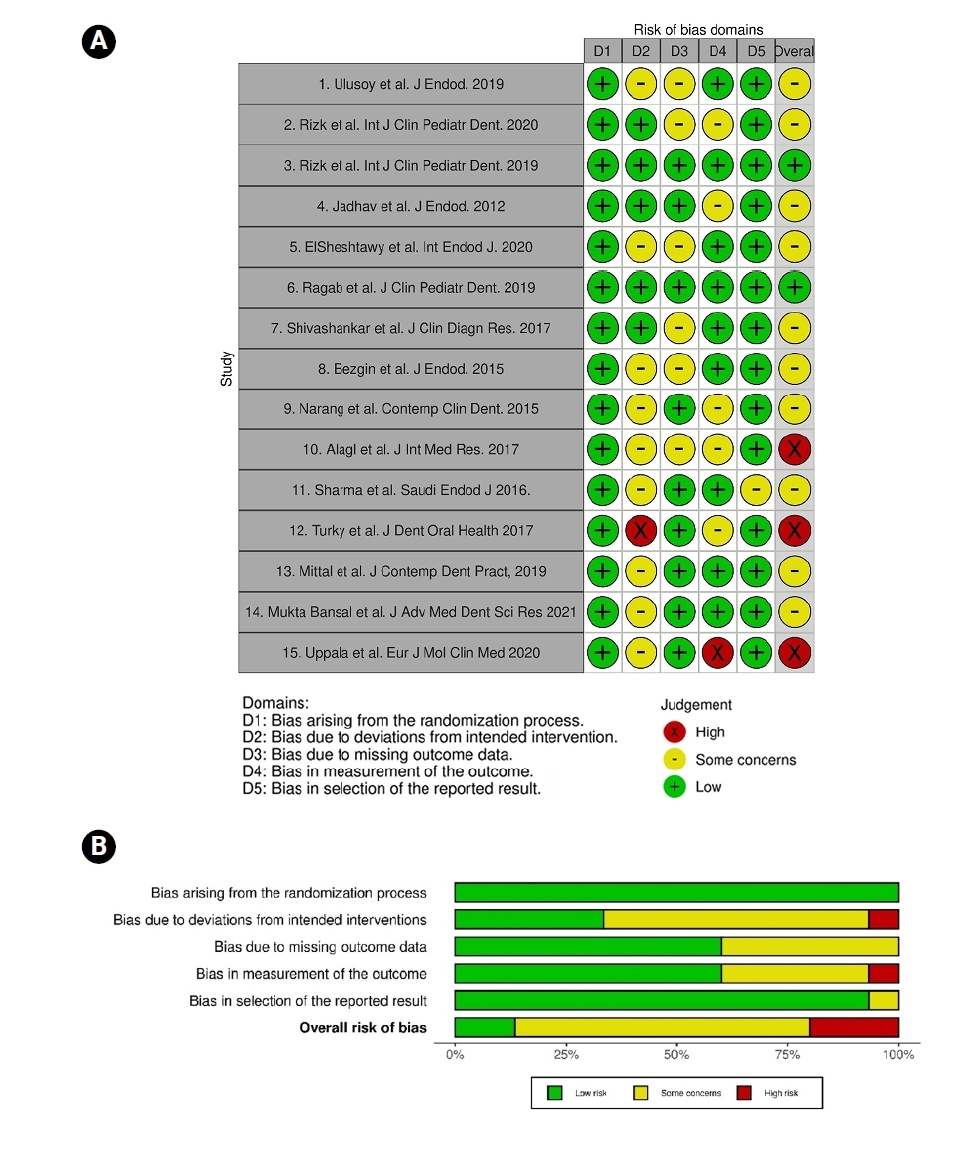

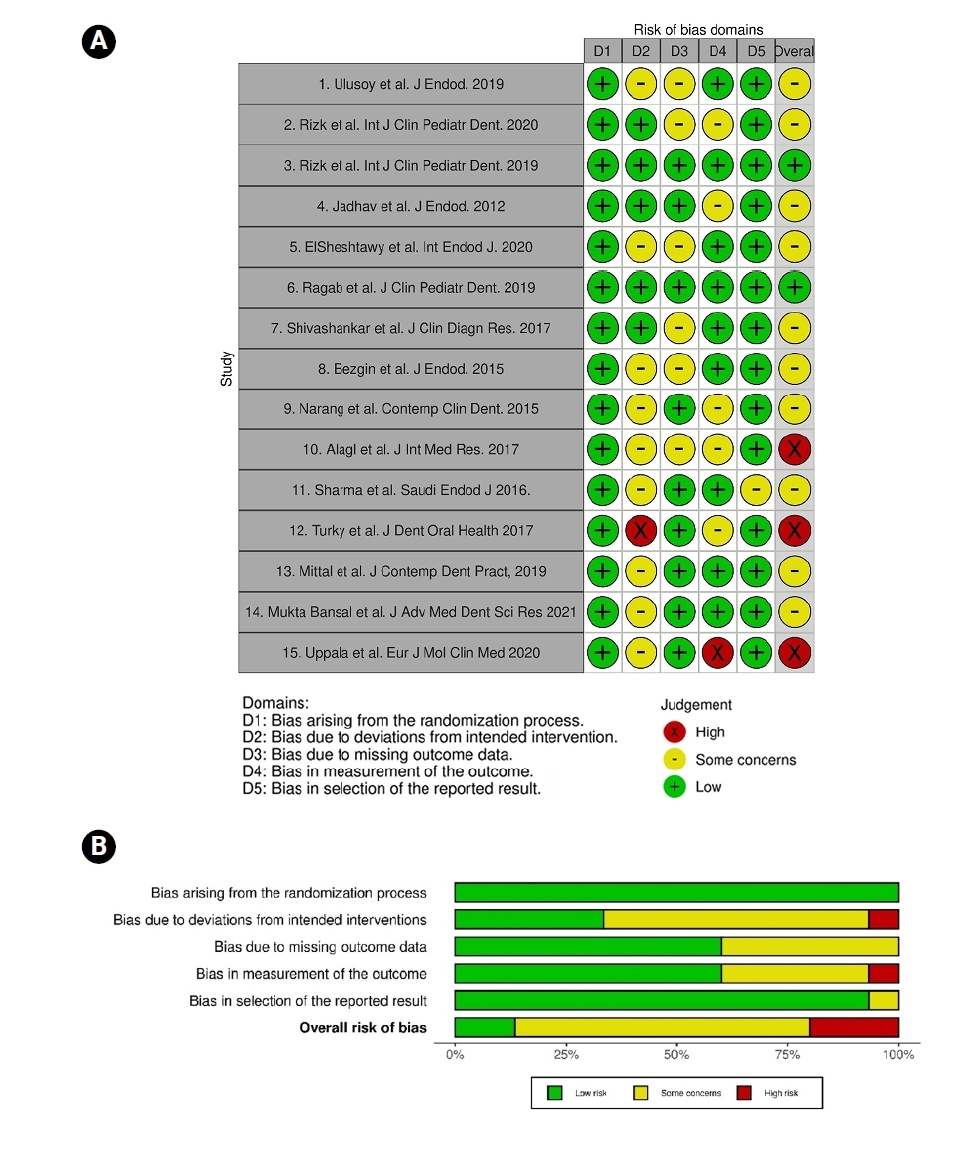

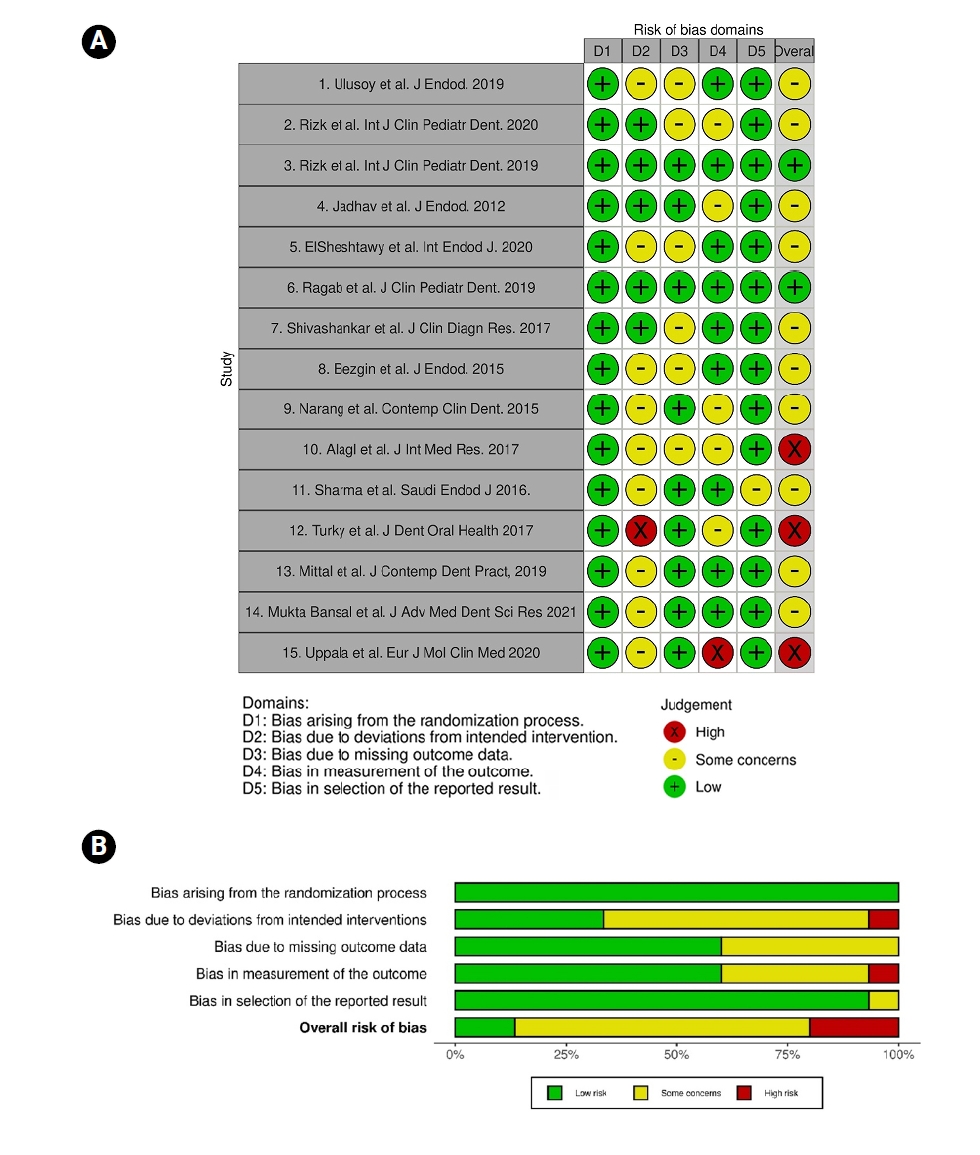

The risk of bias for each included study was independently assessed by two authors (KK, AF), using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool for RCTs, which assesses five domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, handling of missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selective reporting of results [

13]. A study was rated as ‘low risk’ when all domains were judged low risk, as ‘moderate risk’ when at least one domain raised some concerns, and as ‘high risk’ when any domain was identified as high risk. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (NT).

The studies included were assessed using well-defined criteria to ensure that the outcomes were reliable, comparable, and reproducible. These criteria were categorized into three main domains: radiographic assessment, clinical examination, and histological evaluation. Radiographic assessments included tools such as the Periapical Index (PAI), Chen & Chen criteria, and root dimension measurements performed using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). These methods allowed for objective evaluation of root development and periapical healing. Clinical outcomes were evaluated based on the absence of pathological signs or symptoms (eg, pain, swelling, or sinus tract), evidence of periapical healing, tooth survival, and the results of sensibility tests. Histological evaluation of newly regenerated pulp-like tissue involves the identification of key cellular components, including odontoblasts and fibroblasts, as well as the presence of neovascularization and regenerated nerve fibers. Additionally, it assesses the status of inflammation or infection and the integrity of the periodontal ligament, along with the surrounding bone structures [

14].

Meta-analyses were conducted using SPSS software to compare the success rates between PRP or PRF and BC, with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months. Success rates were treated as dichotomous outcomes, and the effect of the interventions was expressed as risk ratios (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The I² statistic was used to assess statistical heterogeneity among studies. In case of low heterogeneity (I² ≤ 50%), a fixed-effect model was applied, while a random-effects model was used in cases of moderate to high heterogeneity. Potential publication bias was assessed both visually through funnel plot inspection. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Study selection

The initial search yielded 4,917 records, from which 4,434 duplicates were removed. After screening the remaining records, 73 were excluded based on title, 191 based on abstract, and 193 based on study design. Additionally, four relevant articles were identified through a manual search. A total of 30 full-text articles were subsequently assessed for eligibility, of which 15 were excluded for various reasons (

Supplementary Table 1). Ultimately, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in both qualitative and quantitative analyses. Of these, 10 studies involved the use of PRP in a total of 124 teeth [

15–

24], eight studies used PRF in 81 teeth [

15,

18,

19,

25–

29], and one study utilized PP in 17 teeth [

15]. Since PP was evaluated in a single trial, it was excluded from the meta-analysis but included in the systematic review. The total number of teeth in the BC group was 165.

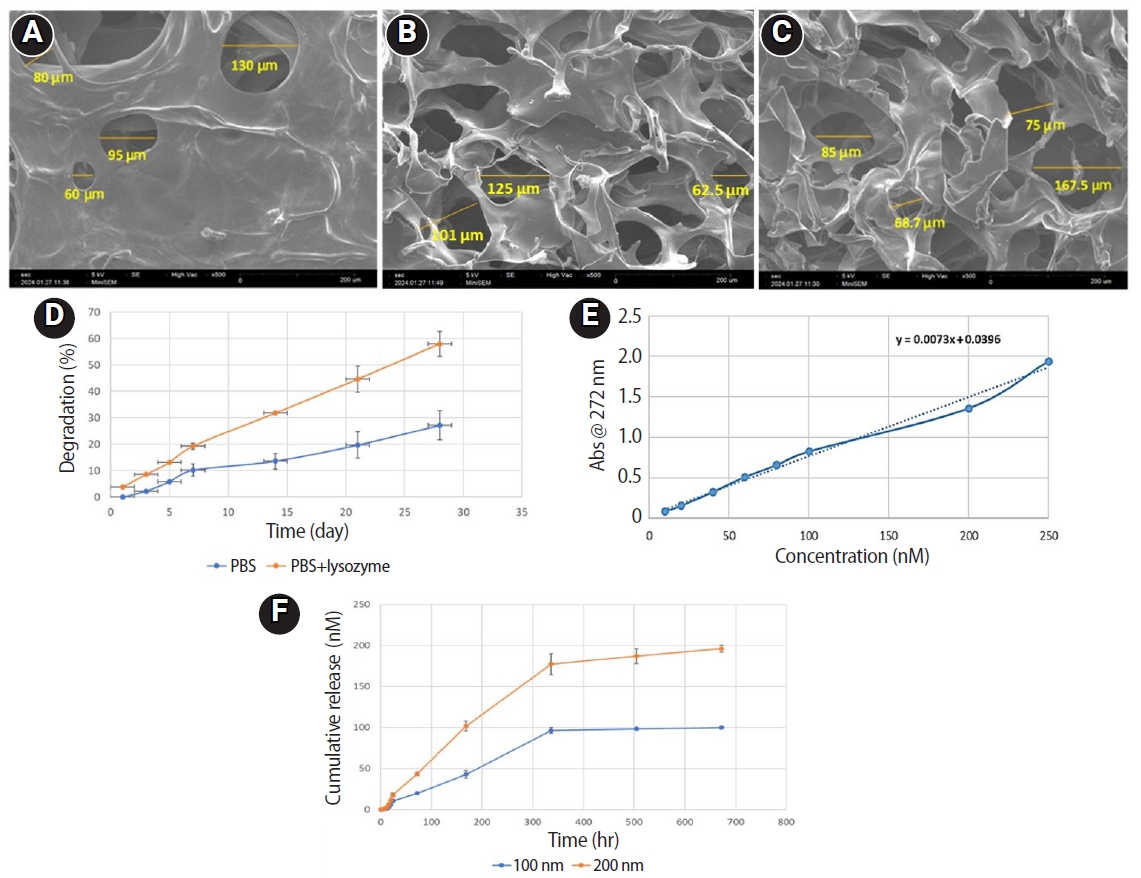

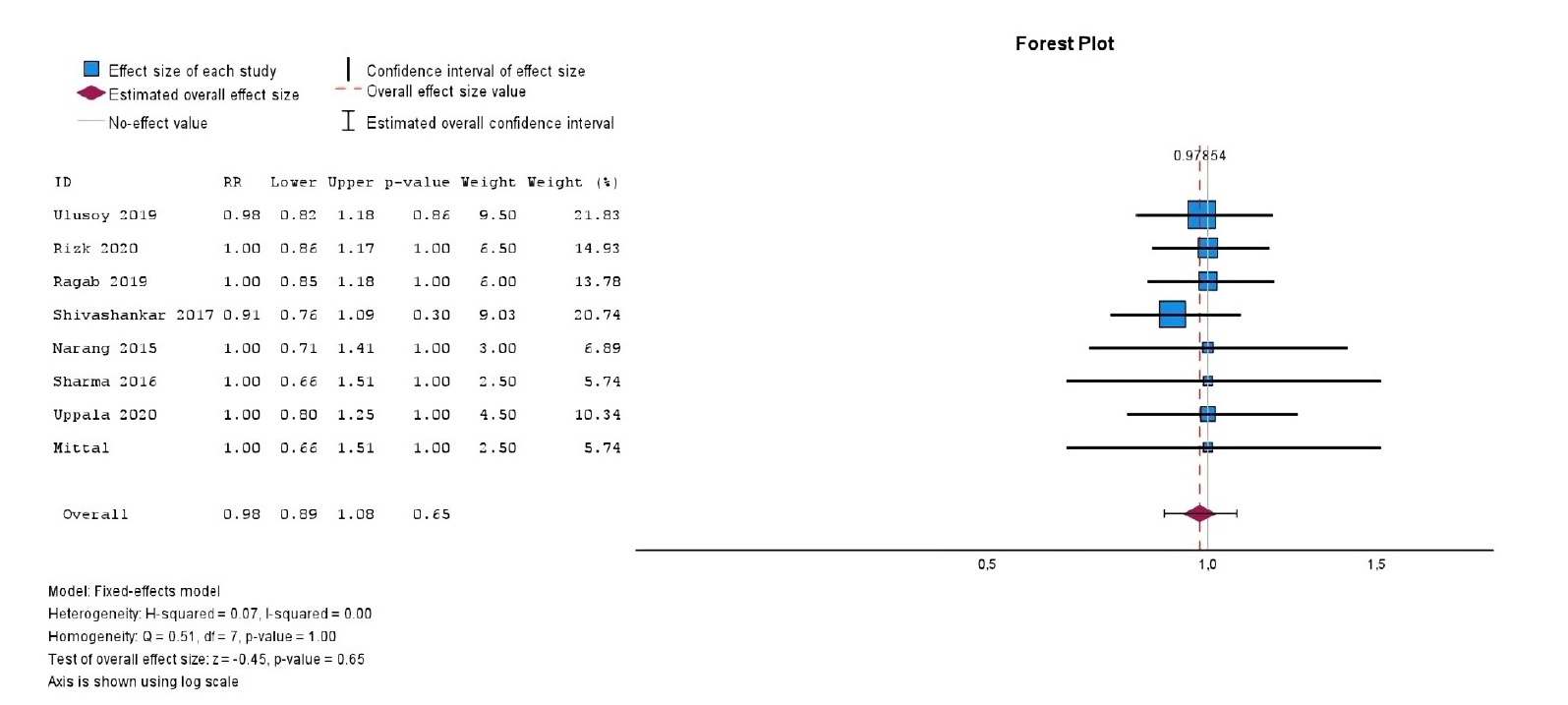

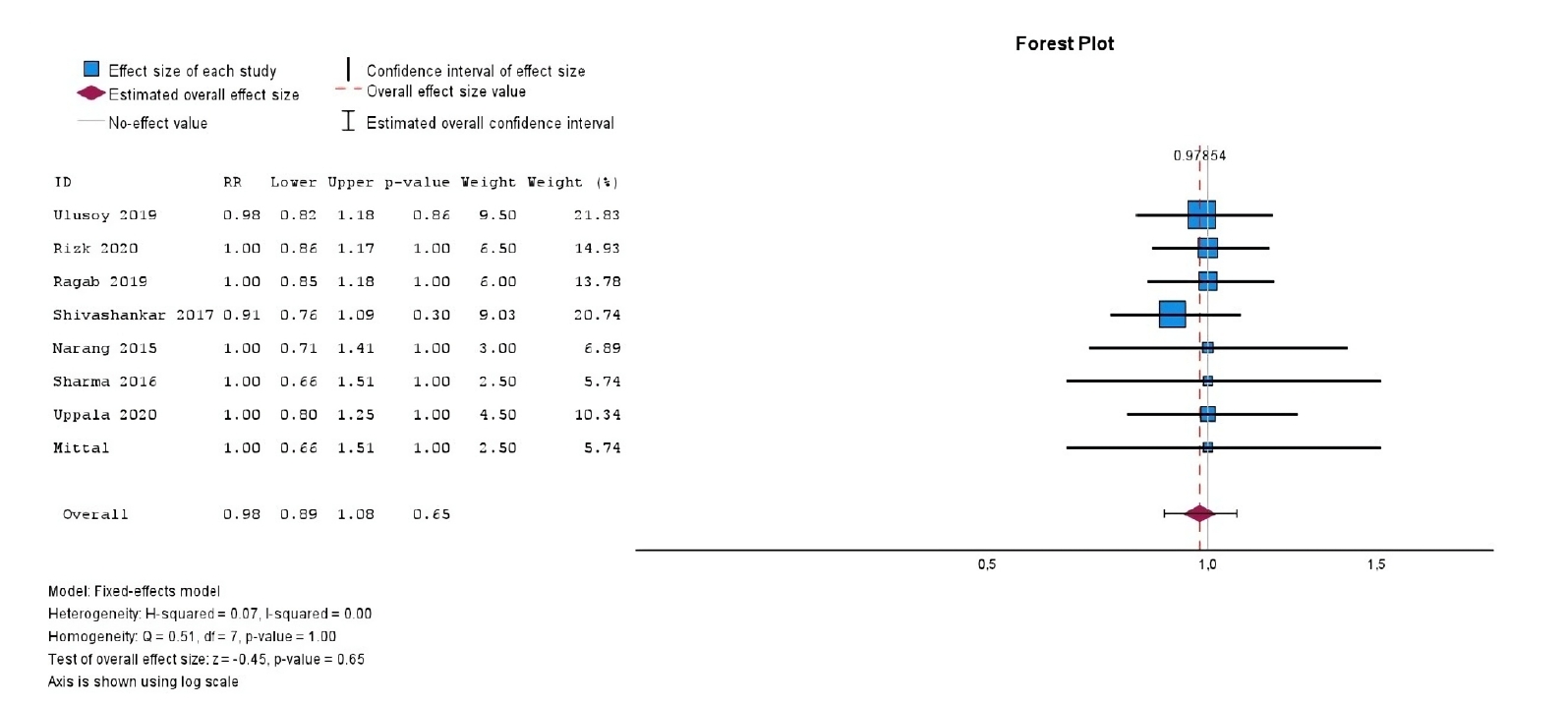

With respect to treatment outcomes, the overall meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the RR between PRP and BC groups (10 studies; RR = 1.01; 95% CI, 0.94–1.09;

p = 0.76) (

Figure 2), nor between PRF and BC groups (eight studies; RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89–1.08;

p = 0.65) (

Figure 3). Furthermore, both comparisons exhibited no heterogeneity (

I² = 0.0%,

p > 0.99), indicating consistency across the included studies.

The outcomes assessed in the included studies were predominantly clinical and radiographic, with a limited number of patient-centered and research-centered outcomes also reported.

The most frequently evaluated radiographic outcomes were: root length (13 studies [

15–

21,

24–

29]), periapical healing lesion (10 studies [

15,

16,

18–

20,

22,

26–

29]), apical closure (10 studies [

15,

16,

19,

20,

22,

23,

26–

29]), dentinal wall thickness (seven studies [

16–

19,

27–

29]), root–radiographic area (four studies [

15,

17,

22,

23]), apical diameter (four studies [

17,

21,

24,

25]), root thickness (three studies [

15,

24,

25]), increase in bone density (three studies [

20,

24,

25]), radiographic canal area (one study [

15]), root canal diameter (one study [

21]), cervical calcification barriers (one study [

26]), root width (one study [

15]), internal/external resorption (one study [

22]), pulp chamber obliteration (one study [

22]). Two studies evaluated the aforementioned measurements as well as periapical area diameter using sagittal and coronal planes of limited field of view CBCT scans [

17,

20].

The most commonly reported clinical outcomes included: sinus fistula formation (nine studies [

15–

17,

19,

20,

22,

24,

25,

27]), swelling (nine studies [

15–

17,

19,

20,

22,

24,

25,]), sensibility test (eight studies of which in six cold testing [

15,

17,

20,

22,

23,

25], in six electric testing [

15,

17,

20,

22,

23,

25], in two heat testing [

17,

25] and in two unknown tests [

18,

24]), sensitivity/tenderness to percussion (six studies [

15,

17,

19,

20,

22,

27]), mobility (four studies [

17,

22,

24,

25]), palpation of soft tissues (three studies [

19,

20,

27]), and other clinical symptoms like infection (two studies [

17,

26]).

Patient-centered outcomes were less frequently reported but included: pain (seven studies [

15,

16,

19,

20,

22,

24,

25]), discoloration (five studies [

17,

22,

24–

26]), and tooth survival (one study [

25]). Research-centered outcomes included PAI (one study [

18]) and apical response (Chen & Chen criteria; one study [

18]).

None of the studies presented histological evidence on regenerated tissues.

Quality assessment of individual studies

The Cochrane Collaboration’s ROB 2.0 tool for RCTs was used to conduct the risk of bias assessment. Of the included studies, 10 were rated as having a low risk of bias across most domains (

Figure 4), while two had a moderate risk of bias, and three were assessed as having a high risk of bias. Overall, the body of evidence was considered to exhibit a low risk of bias. Additionally, there was no evidence of publication bias across any of the performed meta-analyses.

DISCUSSION

Over the years, various treatment modalities have been recommended and implemented for the endodontic management of necrotic teeth with open apices. Traditionally, calcium hydroxide was broadly employed for apexification, requiring multiple treatment sessions to induce apical closure. However, this approach has been increasingly replaced by using mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), which offers superior outcomes and enables more predictable apexogenesis [

30,

31]. In recent years, REPs have gained attention as a promising alternative treatment for these cases. One such technique involves the induction of a BC inside the root canal system to function as a biological scaffold for tissue regeneration. While this method has demonstrated encouraging clinical results [

32], concerns have been raised regarding the presence of numerous hematopoietic cells within the BC. Upon cell death, these cells may release cytotoxic intracellular enzymes into the microenvironment, potentially compromising stem cell viability and thus impairing the regenerative process [

33].

To address these limitations, platelet derivatives have emerged as a modern, biologically favorable alternative. They represent autologous bioactive preparations that can be easily obtained in clinical dental settings by centrifuging the patient’s blood. These autologous biomaterials can enhance stem cell recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation, thereby promoting tissue regeneration and functional recovery. They are rich in growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) [

34,

35]. In addition to their application in endodontics, platelet concentrates have been broadly utilized in regenerative medicine, including periodontal, oral and maxillofacial, dermatologic, and orthopedic procedures [

36].

PRP is an autologous blood-derived product with a platelet concentration increased by at least 2/3 times the normal level. It serves as a biomaterial for the targeted delivery of cytokines and growth factors from platelet granules, thereby promoting tissue regeneration. PRP has been applied as a novel regeneration method in various damaged tissues, such as bone, liver, dental pulp, cartilage, and tendon [

37,

38].

PRF is a second-generation platelet derivative that consists of a fibrin matrix rich in platelets, leukocytes, cytokines, and growth factors, including interleukins (ILs), ie, IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-6, vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and TGF-β1. All these components are gradually released over time, enhancing their regenerative potential. PRF has been effectively used in different therapeutic applications like sinus lift augmentation, extraction socket healing, and guided bone regeneration. In regenerative endodontics, it is utilized in cases of iatrogenic pulpal floor perforations as well as revascularization of immature necrotic permanent teeth [

8,

39,

40].

PP is a platelet derivative with a significantly greater platelet content compared to PRP, containing approximately 12 times more platelets and TGF-β1 compared to PRP, and 17 times more than whole blood, while exhibiting a lower white blood cell content [

41]. Its gel-like consistency enhances its adhesive properties, making it a promising scaffold for regenerative applications [

42].

In the present systematic review, a total of 15 studies were included for analysis, each investigating the application of various platelet derivatives in REPs. More than half of the studies employed PRP (10 studies), whereas PRF was used in eight studies. Despite the greater frequency of PRP use across the selected studies, PRF is often preferred over PRP as a scaffold in REPs, due to PRF’s ability to provide a continuous release of growth factors for an extended time period and its superior mechanical properties [

35,

43]. Additionally, PRF offers practical advantages: it is completely autologous and does not require anticoagulants [

40,

44]. PP, which was evaluated in only one study, is characterized by an increased platelet concentration and associated growth factors, offering enhanced regenerative potential. However, the current body of evidence remains insufficient to confirm its clinical superiority over PRP or PRF [

42]. In contrast, BC is a cost-effective option compared to PRF, PRP, and PP as it uses the patient’s own blood without additional processing. However, BC has limitations such as instability and lower platelets and growth factor content compared to platelet derivatives [

45,

46].

The sample sizes across the 15 included studies varied from four to 21 for the BC group, five to 19 for PRP, four to 20 for PRF, and 17 for PP. Notably, nearly half of them did not report using a sample size calculation method, nor did they provide clear details regarding randomization procedures. Furthermore, none of the studies comparing BC with PRP, PRF, or PP included more than 21 participants. These limitations highlight the need for future research with larger, well-powered samples and rigorous methodological standards to produce more definitive and generalizable findings in this field.

In nine out of the 15 studies, incisors were the most frequently treated tooth type [

15,

17,

21,

24–

29]. Among these, all but one study [

17] focused exclusively on maxillary incisors, with five studies specifically targeting central incisors [

21,

24–

26,

29]. Two studies included anterior teeth [

16,

18], while three studies treated both incisors and single-rooted premolars [

20,

22,

23]. One study did not specify the tooth type beyond identifying them as immature permanent teeth [

19]. The predominance of single-rooted teeth in these studies may be attributed to their simpler root canal anatomy, which facilitates standardization, treatment consistency, and outcome evaluation by minimizing anatomical variability and confounding factors.

Out of the 15 studies, MTA was primarily used as a barrier over the scaffold in six studies [

15,

18,

20–

22,

26], while four studies incorporated glass ionomer cement (GIC) either between the MTA and the final restoration material or as the final restoration itself [

15,

20,

22,

26]. One study used MTA for the entire permanent restoration [

23]. Two studies used collagen covered with MTA, followed by GIC [

17,

24], while two other studies used GIC alone [

19,

28]. Four studies did not use a barrier over the scaffold [

16,

23,

27,

29]. One study used a combination of biomaterials (MTA for the PRP group and collagen with MTA for the BC group), covered with a layer of GIC [

25]. MTA is favored as a barrier due to its biocompatibility, ability to set in a moist environment and form a good seal, and capacity to stimulate hard tissue formation (dentin bridge formation) [

47,

48]. Collagen functions as an apical matrix that can prevent MTA over-extrusion and aid in periapical tissue healing [

49].

When compared with GIC, MTA provides a better seal, but it sets more slowly [

47,

50,

51]. Applying a layer of GIC over MTA may improve results, whereas using only GIC simplifies the procedure. However, immediate sealing without a barrier over the scaffold can result in issues such as polymerization shrinkage and subsequent microleakage, which can lead to scaffold contamination. Additionally, resin toxicity raises some concerns [

52]. These factors must be considered when selecting a barrier material for scaffold restoration procedures.

Regarding the materials used for the final restoration, composite resin was employed in nine out of the 15 studies [

15,

17,

19–

22,

24,

25,

28], with all but one [

21] placing it over a GIC base. However, two studies did not clearly specify the final restoration material used for the BC group [

24,

25]. GIC alone was used as the final restorative material in four studies [

16,

26,

27,

29]. Additionally, one study utilized MTA for the final restoration, although it did not provide specific data for the BC group [

23].

Composite resin is commonly preferred for final restorations due to its favorable aesthetic properties, mechanical strength, and durability. However, it presents certain limitations, including polymerization shrinkage and technique sensitivity, which require a controlled, dry operating field and the application of a meticulous layering technique [

53,

54]. Meanwhile, GIC tolerates moisture but has lower strength and durability [

55,

56]. Composite resin restorations have demonstrated superior longevity and overall clinical performance in comparison to other materials [

57,

58]. In contrast, MTA, though utilized in one study, may be less favored due to its prolonged setting time and handling difficulties [

47]. Regardless of the material chosen, the success of the final restoration depends primarily on its ability to prevent microleakage and effectively seal the access cavity, thereby protecting the underlying scaffold from exposure to oral microorganisms and potential infection.

Permanent restoration was completed during the same visit in nine studies [

15,

16,

19,

20,

22,

23,

27–

29] with one study specifying a 45-minute time frame before restoration [

26]. In one study, restoration was completed after 24 hours [

17], or after 1 week [

21], and in two studies after 3 days, with no data for the BC group in these cases [

24,

25]. Finally, one study failed to provide data on the type or timing of permanent restoration [

18].

Overall, composite resin is a popular choice for final restorations due to its aesthetic and functional benefits, while GIC and MTA are also used in certain cases. Timing and material selection play crucial roles in the success of the restoration procedure.

Comparative results

There have been rapid advancements in regenerative endodontics in recent years, with new original research articles and reviews examining the efficiency of different materials such as scaffolds. A meta-analysis by Murray [

59] concluded that platelet concentrates promoted apical closure more often compared to BC scaffolds, with similar success rates, periapical healing, and dentin wall thickening. However, it is worth noting that the design of the included studies is not described. Panda

et al. [

60] reviewed RCTs and other comparative studies and found no significant differences in dentin wall thickness, root length increase, or success rate between PRP or PRF and BC. However, in terms of vitality response and apical closure, PRP showed better results compared to BC. Another study by Panda

et al. [

32] compared regenerative interventions with apexification and different scaffolds from randomized and non-randomized trials with a follow-up period of ≥6 months and concluded that PRP and PRF yielded similar results to BC regarding apical closure, root length increase, and dentin wall thickness. Nevertheless, while REPs with PRP had a comparable success rate to those with BC, REPs with advanced platelet concentrates (it is not specified whether PRP or PRF was used) had a significantly better vitality response than those with BC.

In contrast to some of the outcomes presented in the aforementioned studies, the present systematic review found no statistical difference in the success rate of RETs using PRP or PRF compared to BC techniques. Similarly, Rios-Osorio

et al. [

61] concluded that BC scaffolds produce comparable clinical and radiographic results to platelet concentrates, without following a meta-analysis approach.

As for meta-analyses comparing platelet derivatives with the BC technique in RETs, important methodological differences distinguish our review from earlier reports. Rahul

et al. [

62] conducted their search in 2021 and included RCTs, non-RCTs, and prospective cohort studies with ≥12 months of follow-up. Using a network meta-analysis, they reported comparable outcomes between PRP, PRF, and BC in terms of clinical success, apical closure, and pulp sensitivity. Likewise, Verma

et al. [

63] combined RCTs with multiple non-randomized designs, including case studies, case reports, and retrospective studies, to evaluate PRP and PRF against BC. In contrast, this review is the first to restrict inclusion exclusively to RCTs with ≥12 months’ follow-up, thereby ensuring the highest level of evidence. Moreover, indirect comparisons and the use of combined experimental arms with heterogeneous controls were avoided to achieve direct head-to-head comparisons of PRP, PRF, and PP versus BC, yielding results that are both robust and clinically relevant. For instance, RCTs like the one by Rizk

et al. [

64] or Santhakumar

et al. [

65] that do not include a BC group were excluded in this study (

Supplementary Table 1). Further heterogeneity was also restricted by avoiding pooling experimental groups where growth factors or other tissue-inductive molecules were used in combination with PRP or PRF [

66]. Overall, this meta-analysis provides the most up-to-date and comprehensive dataset, avoiding any heterogeneity issues and ensuring methodological rigor and transparency by utilizing the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool for bias assessment.

The limited number of randomized studies has created a research gap in this scientific field, despite some original research on this topic. Additionally, there is a lack of standardized evaluation criteria for the success of RETs. Various metrics, including clinical success, radiographic success, dentin wall thickness, increased root length, pulp sensitivity, and apical closure/periapical healing have been used in different studies and reviews, making it challenging to draw clear conclusions. Histological evaluation should play the most critical role in evaluating success by determining the type, organization, and cellular composition of newly regenerated pulp-like tissue. This includes the identification of key cellular components such as odontoblasts, fibroblasts, or mineralized tissue, the presence of newly formed blood vessels, regenerated nerve fibers, as well as the status of inflammation or infection, periodontal ligament integrity, and the condition of surrounding bone structures [

14]. However, obtaining such histological data in a clinical setting is often challenging and may raise ethical concerns. Overall, more randomized studies, with standardized criteria, are needed to generate original clinical data and metrics for analysis, facilitating more accurate clinical decision-making.

This systematic review has several limitations. Publication bias may exist as only published studies from five main databases were included, potentially missing studies in other databases, grey literature, or unpublished sources. Language restrictions limited inclusion to English studies, possibly excluding relevant research in other languages. Finally, only studies with immature teeth, recall times over 12 months, and a BC control group were included, potentially missing other important outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review suggests that PRP, PRF, and BC present viable and clinically successful approaches for the RET of immature permanent teeth with pulp necrosis. While platelet derivatives may offer potential biological advantages, current evidence does not demonstrate significant statistical superiority in terms of clinical and radiographic success. Moreover, the lack of long-term follow-up data limits the strength of any definitive clinical recommendations. Future research should prioritize carefully planned RCTs with longer recall periods, larger sample sizes, standardized outcome measures, and, where possible, histological evaluation of human teeth to provide more robust evidence and clearer clinical guidance.

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Project administration: Kodonas K. Data curation: Tsiolaki A, Theocharis D. Formal analysis: Fardi A, Kodonas K. Investigation: Tsiolaki A, Theocharis D, Tsitsipas N. Methodology: Tsitsipas N, Fardi A, Kodonas K. Supervision: Kodonas K, Fardi A. Visualization: all authors. Writing - original draft: Tsiolaki A, Theocharis D, Tsitsipas N. Writing - review & editing: Fardi A, Kodonas K. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The datasets are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Figure 1.Flow diagram of the search process.

Figure 2.Forest plot showing the RR for treatment outcomes between platelet-rich plasma and blood clot.

Figure 3.Forest plot showing the RR for treatment outcomes between platelet-rich fibrin and blood clot.

Figure 4.(A) A summary of the risk of bias in the included studies and (B) a review of the authors’ judgements about each risk of bias domain as percentages across the included studies.

Table 1.

|

Databases |

Search strategy |

|

MEDLINE (PubMed) |

((((((((((("platelet rich plasma"[All Fields]) OR ("platelet rich fibrin"[All Fields])) OR ("platelet gel"[All Fields])) OR ("platelet concentrated"[All Fields])) OR ("platelet concentrate"[All Fields])) OR ("platelet pellet"[All Fields])) OR ("prp"[All Fields])) OR ("prf"[All Fields])) OR ("pp"[All Fields])) OR ("platelet rich plasma"[MeSH Terms])) OR ("platelet rich fibrin"[MeSH Terms])) AND (((((("regenerative endodontics"[All Fields]) OR ("apexification"[All Fields])) OR ("pulp revascularization"[All Fields])) OR ("pulp revitalization"[All Fields])) OR ("regenerative endodontics"[MeSH Terms])) OR ("apexification"[MeSH Terms])) |

|

Separate combined searches of each of the terms from group #1 AND group #2 |

|

1) “platelet rich plasma"[All Fields], "platelet rich fibrin"[All Fields], "platelet gel"[All Fields], "platelet concentrated"[All Fields], "platelet concentrate"[All Fields], ("platelet pellet"[All Fields], "prp"[All Fields], "prf"[All Fields], "pp"[All Fields], "platelet rich plasma"[MeSH Terms], "platelet rich fibrin"[MeSH Terms] |

|

2) "regenerative endodontics"[All Fields], "apexification"[All Fields], "pulp revascularization"[All Fields], "pulp revitalization"[All Fields], "regenerative endodontics"[MeSH Terms], "apexification"[MeSH Terms] |

|

Elsevier Scopus |

((TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND rich AND plasma) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND rich AND fibrin) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND concentrated) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND concentrate) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND pellet) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND gel) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (prp) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (prf) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (pp))) AND ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (regenerative AND endodontics) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (apexification) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (pulp AND revascularization) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (pulp AND revitalization))) |

|

Separate combined searches of each of the terms from group #1 AND group #2 |

|

1) TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND rich AND plasma), TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND rich AND fibrin), TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND concentrated), TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND concentrate), TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND pellet), TITLE-ABS-KEY (platelet AND gel), TITLE-ABS-KEY (prp), TITLE-ABS-KEY (prf), TITLE-ABS-KEY (pp) |

|

2) TITLE-ABS-KEY (regenerative AND endodontics), TITLE-ABS-KEY (apexification), TITLE-ABS-KEY (pulp AND revascularization), TITLE-ABS-KEY (pulp AND revitalization) |

|

Cochrane Library |

("platelet rich plasma" or "platelet rich fibrin" or "platelet gel" or "platelet concentrated" or “platelet concentrate” or "platelet pellet" or "PRP" or "PRF" or "PP") and ("Regenerative Endodontics" or "Apexification" or "pulp revitalization" or “pulp revascularization”) |

|

Web of Science Core Collection |

The following searches were combined (1 AND #2): |

|

1) ((((((((ALL= (platelet rich plasma)) OR ALL=(platelet rich fibrin)) OR ALL= (platelet concentrate)) OR ALL= (platelet concentrated)) OR ALL=(platelet pellet)) OR ALL=(platelet gel)) OR ALL=(PRP)) OR ALL=(PRF)) OR ALL=(PP) |

|

2) (((ALL= (regenerative endodontics)) OR ALL=(apexification)) OR ALL=(pulp revascularization)) OR ALL= (pulp revitalization) |

|

Separate combined searches of each the terms from group #1 AND #2: |

|

1) ALL=(platelet rich plasma), ALL=(platelet rich fibrin), ALL= (platelet concentrate), ALL=(platelet concentrated), ALL= (platelet pellet), ALL= (platelet gel), ALL=(PRP), ALL=(PRF), ALL=(PP) |

|

2) ALL= (regenerative endodontics), ALL=(apexification), ALL= (pulp revascularization), ALL= (pulp revitalization) |

|

Web of Science All Databases |

The following searches were combined (1 AND #2): |

|

1) ((((((((TS= (platelet rich plasma)) OR TS= (platelet rich fibrin)) OR TS= (platelet concentrated)) OR TS= (platelet concentrate)) OR TS= (platelet pellet)) OR TS= (platelet gel)) OR TS= (PRP)) OR TS=(PRF)) OR TS=(PP) |

|

2) (((TS= (regenerative endodontics)) OR TS= (apexification)) OR TS=(pulp revascularization) OR TS=(pulp revitalization) |

|

Separate combined searches of each of the terms from group #1 AND group #2: |

|

1) TS= (platelet rich plasma), TS= (platelet rich fibrin), TS=(platelet concentrated), TS= (platelet concentrate), TS=(platelet pellet), TS=(platelet gel), TS=(PRP), TS= (PRF), TS= (PP) |

|

2) TS=(regenerative endodontics), TS=(apexification), TS=(pulp revascularization), TS= (pulp revitalization) |

REFERENCES

- 1. Feigin K, Shope B. Regenerative endodontics. J Vet Dent 2017;34:161-178.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Rojas-Gutiérrez WJ; Pineda-Vélez E; Agudelo-Suárez AA. Regenerative endodontics success factors and their overall effectiveness: an umbrella review. Iran Endod J 2022;17:90-105.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Pulyodan MK, Paramel Mohan S, Valsan D, Divakar N, Moyin S, Thayyil S. Regenerative endodontics: a paradigm shift in clinical endodontics. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2020;12:S20-S26.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Kim SG, Malek M, Sigurdsson A, Lin LM, Kahler B. Regenerative endodontics: a comprehensive review. Int Endod J 2018;51:1367-1388.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Murray PE, Garcia-Godoy F, Hargreaves KM. Regenerative endodontics: a review of current status and a call for action. J Endod 2007;33:377-390.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Yan H, De Deus G, Kristoffersen IM, Wiig E, Reseland JE, Johnsen GF, et al. Regenerative endodontics by cell homing: a review of recent clinical trials. J Endod 2023;49:4-17.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Yang J, Yuan G, Chen Z. Pulp regeneration: current approaches and future challenges. Front Physiol 2016;7:58.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Arshad S, Tehreem F, Rehab Khan M, Ahmed F, Marya A, Karobari MI. Platelet-rich fibrin used in regenerative endodontics and dentistry: current uses, limitations, and future recommendations for application. Int J Dent 2021;2021:4514598.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Juárez DM, Chargoy NI. Blood clot in regenerative endodontic therapy of immature permanent teeth: a review of the literature. Mex J Med Res ICSA 2024;12:58-66.ArticlePDF

- 10. Lin J, Zeng Q, Wei X, Zhao W, Cui M, Gu J, et al. Regenerative endodontics versus apexification in immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Endod 2017;43:1821-1827.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Galler KM, Krastl G, Simon S, Van Gorp G, Meschi N, Vahedi B, et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: revitalization procedures. Int Endod J 2016;49:717-723.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2021;74:790-799.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Digka A, Sakka D, Lyroudia K. Histological assessment of human regenerative endodontic procedures (REP) of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulp/apical periodontitis: a systematic review. Aust Endod J 2020;46:140-153.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Ulusoy AT, Turedi I, Cimen M, Cehreli ZC. Evaluation of blood clot, platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich fibrin, and platelet pellet as scaffolds in regenerative endodontic treatment: a prospective randomized trial. J Endod 2019;45:560-566.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Jadhav G, Shah N, Logani A. Revascularization with and without platelet-rich plasma in nonvital, immature, anterior teeth: a pilot clinical study. J Endod 2012;38:1581-1587.ArticlePubMed

- 17. ElSheshtawy AS, Nazzal H, El Shahawy OI, El Baz AA, Ismail SM, Kang J, et al. The effect of platelet-rich plasma as a scaffold in regeneration/revitalization endodontics of immature permanent teeth assessed using 2-dimensional radiographs and cone beam computed tomography: a randomized controlled trial. Int Endod J 2020;53:905-921.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Shivashankar VY, Johns DA, Maroli RK, Sekar M, Chandrasekaran R, Karthikeyan S, et al. Comparison of the effect of PRP, PRF and induced bleeding in the revascularization of teeth with necrotic pulp and open apex: a triple blind randomized clinical trial. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11:ZC34-ZC39.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Narang I, Mittal N, Mishra N. A comparative evaluation of the blood clot, platelet-rich plasma, and platelet-rich fibrin in regeneration of necrotic immature permanent teeth: a clinical study. Contemp Clin Dent 2015;6:63-68.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Alagl A, Bedi S, Hassan K, AlHumaid J. Use of platelet-rich plasma for regeneration in non-vital immature permanent teeth: clinical and cone-beam computed tomography evaluation. J Int Med Res 2017;45:583-593.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 21. Turky M, Kataia MA, Ali MM, Hassan RE. Revascularization induced maturogenesis of human non-vital immature teeth via platelets-rich plasma (PRP): radiographic study. J Dent Oral Heal 2017;3:97.

- 22. Bezgin T, Yilmaz AD, Celik BN, Kolsuz ME, Sonmez H. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma as a scaffold in regenerative endodontic treatment. J Endod 2015;41:36-44.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Bansal M, Sawhny A, Singh R, Sharma S, Priyadarshi PK, Paul S. Evaluation of efficacy of platelet rich plasma as a scaffold in regenerative endodontic treatment: an in-vivo study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2021;12:2750-2758.

- 24. Rizk HM, Salah Al-Deen MS, Emam AA. Pulp revascularization/revitalization of bilateral upper necrotic immature permanent central incisors with blood clot vs platelet-rich fibrin scaffolds-a split-mouth double-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2020;13:337-343.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Rizk HM, Al-Deen MS, Emam AA. Regenerative endodontic treatment of bilateral necrotic immature permanent maxillary central incisors with platelet-rich plasma versus blood clot: a split mouth double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2019;12:332-339.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Ragab RA, Lattif AE, Dokky NA. Comparative study between revitalization of necrotic immature permanent anterior teeth with and without platelet rich fibrin: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2019;43:78-85.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 27. Sharma S, Mittal N. A comparative evaluation of natural and artificial scaffolds in regenerative endodontics: a clinical study. Saudi Endod J 2016;6:9-15.Article

- 28. Mittal N, Parashar V. Regenerative evaluation of immature roots using PRF and artificial scaffolds in necrotic permanent teeth: a clinical study. J Contemp Dent Pract 2019;20:720-726.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Uppala S. A comparative evaluation of PRF, blood clot and collagen scaffold in regenerative endodontics. Eur J Mol Clin Med 2020;7:3401-3410.

- 30. Purra AR, Ahangar FA, Chadgal S, Farooq R. Mineral trioxide aggregate apexification: a novel approach. J Conserv Dent 2016;19:377-380.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Guerrero F, Mendoza A, Ribas D, Aspiazu K. Apexification: a systematic review. J Conserv Dent 2018;21:462-465.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Panda P, Mishra L, Govind S, Panda S, Lapinska B. Clinical outcome and comparison of regenerative and apexification intervention in young immature necrotic teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2022;11:3909.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Wei X, Yang M, Yue L, Huang D, Zhou X, Wang X, et al. Expert consensus on regenerative endodontic procedures. Int J Oral Sci 2022;14:55.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 34. Mehta S, Watson JT. Platelet rich concentrate: basic science and current clinical applications. J Orthop Trauma 2008;22:432-438.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Kobayashi E, Flückiger L, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Sawada K, Sculean A, Schaller B, et al. Comparative release of growth factors from PRP, PRF, and advanced-PRF. Clin Oral Investig 2016;20:2353-2360.ArticlePubMed

- 36. De Pascale MR, Sommese L, Casamassimi A, Napoli C. Platelet derivatives in regenerative medicine: an update. Transfus Med Rev 2015;29:52-61.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Xu J, Gou L, Zhang P, Li H, Qiu S. Platelet-rich plasma and regenerative dentistry. Aust Dent J 2020;65:131-142.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 38. Gupta S, Paliczak A, Delgado D. Evidence-based indications of platelet-rich plasma therapy. Expert Rev Hematol 2021;14:97-108.ArticlePubMed

- 39. Naik B, Karunakar P, Jayadev M, Marshal VR. Role of Platelet rich fibrin in wound healing: a critical review. J Conserv Dent 2013;16:284-293.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part II: platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006;101:e45-e50.ArticlePubMed

- 41. Dugrillon A, Eichler H, Kern S, Klüter H. Autologous concentrated platelet-rich plasma (cPRP) for local application in bone regeneration. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;31:615-619.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Keles GC, Cetinkaya BO, Albayrak D, Koprulu H, Acikgoz G. Comparison of platelet pellet and bioactive glass in periodontal regenerative therapy. Acta Odontol Scand 2006;64:327-333.ArticlePubMed

- 43. Khiste SV, Naik Tari R. Platelet‐rich fibrin as a biofuel for tissue regeneration. Int Sch Res Not 2013;2013:627367.ArticlePDF

- 44. Oneto P, Zubiry PR, Schattner M, Etulain J. Anticoagulants interfere with the angiogenic and regenerative responses mediated by platelets. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020;8:223.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 45. Dissanayaka WL, Zhang C. Scaffold-based and scaffold-free strategies in dental pulp regeneration. J Endod 2020;46:S81-S89.ArticlePubMed

- 46. Liu H, Lu J, Jiang Q, Haapasalo M, Qian J, Tay FR, et al. Biomaterial scaffolds for clinical procedures in endodontic regeneration. Bioact Mater 2022;12:257-277.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 47. Tawil PZ, Duggan DJ, Galicia JC. Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA): its history, composition, and clinical applications. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2015;36:247-252.PubMedPMC

- 48. Parirokh M, Torabinejad M. Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review: part III: clinical applications, drawbacks, and mechanism of action. J Endod 2010;36:400-413.ArticlePubMed

- 49. Tek GB, Keskin G. Use of mineral trioxide aggregate with or without a collagen sponge as an apical plug in teeth with immature apices. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2021;45:165-170.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 50. Nicholson JW. Maturation processes in glass-ionomer dental cements. Acta Biomater Odontol Scand 2018;4:63-71.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 51. Tavakoli M, Araghi S, Fathi A, Jalalian S. Comparison of coronal sealing of flowable composite, resin-modified glass ionomer, and mineral trioxide aggregate in endodontically treated teeth: an in-vitro study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2024;21:13.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 52. Moharamzadeh K, Brook IM, Van Noort R. Biocompatibility of resin-based dental materials. Materials 2009;2:514-548.ArticlePMC

- 53. Soares CJ, Faria-E-Silva AL, Rodrigues MP, Vilela ABF, Pfeifer CS, Tantbirojn D, et al. Polymerization shrinkage stress of composite resins and resin cements: what do we need to know? Braz Oral Res 2017;31:e62.ArticlePubMed

- 54. Chandrasekhar V, Rudrapati L, Badami V, Tummala M. Incremental techniques in direct composite restoration. J Conserv Dent 2017;20:386-391.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 55. Sidhu SK. Glass-ionomer cement restorative materials: a sticky subject? Aust Dent J 2011;56 Suppl 1:23-30.ArticlePubMed

- 56. Bowen RL, Marjenhoff WA. Dental composites/glass ionomers: the materials. Adv Dent Res 1992;6:44-49.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 57. Heintze SD, Loguercio AD, Hanzen TA, Reis A, Rousson V. Clinical efficacy of resin-based direct posterior restorations and glass-ionomer restorations: an updated meta-analysis of clinical outcome parameters. Dent Mater 2022;38:e109-e135.ArticlePubMed

- 58. Balkaya H, Arslan S, Pala K. A randomized, prospective clinical study evaluating effectiveness of a bulk-fill composite resin, a conventional composite resin and a reinforced glass ionomer in Class II cavities: one-year results. J Appl Oral Sci 2019;27:e20180678.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 59. Murray PE. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet-rich fibrin can induce apical closure more frequently than blood-clot revascularization for the regeneration of immature permanent teeth: a meta-analysis of clinical efficacy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018;6:139.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 60. Panda S, Mishra L, Arbildo-Vega HI, Lapinska B; Lukomska-Szymanska M, Khijmatgar S, et al. Effectiveness of autologous platelet concentrates in management of young immature necrotic permanent teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cells 2020;9:2241.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 61. Ríos-Osorio N, Caviedes-Bucheli J; Jimenez-Peña O, Orozco-Agudelo M, Mosquera-Guevara L; Jiménez-Castellanos FA, et al. Comparative outcomes of platelet concentrates and blood clot scaffolds for regenerative endodontic procedures: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Clin Exp Dent 2023;15:e239-e249.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 62. Rahul M, Lokade A, Tewari N, Mathur V, Agarwal D, Goel S, et al. Effect of intracanal scaffolds on the success outcomes of regenerative endodontic therapy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Endod 2023;49:110-128.ArticlePubMed

- 63. Verma S, Gupta A, Mrinalini M, Abraham D, Soma U. Comparative evaluation of autologous platelet aggregates versus blood clot on the outcome of regenerative endodontic therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Exp Dent 2025;17:e447-e460.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 64. Rizk HM, Salah Al-Deen MSM, Emam AA. Comparative evaluation of Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) versus Platelet Rich Fibrin (PRF) scaffolds in regenerative endodontic treatment of immature necrotic permanent maxillary central incisors: a double blinded randomized controlled trial. Saudi Dent J 2020;32:224-231.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 65. Santhakumar M, Yayathi S, Retnakumari N. A clinicoradiographic comparison of the effects of platelet-rich fibrin gel and platelet-rich fibrin membrane as scaffolds in the apexification treatment of young permanent teeth. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2018;36:65-70.ArticlePubMed

- 66. Yang F, Yu L, Li J, Cheng J, Zhang Y, Zhao X, et al. Evaluation of concentrated growth factor and blood clot as scaffolds in regenerative endodontic procedures: a retrospective study. Aust Endod J 2023;49:332-343.ArticlePubMedPDF

, Dimitrios Theocharis1

, Dimitrios Theocharis1 , Nikolaos Tsitsipas1,*

, Nikolaos Tsitsipas1,* , Anastasia Fardi2

, Anastasia Fardi2 , Konstantinos Kodonas3

, Konstantinos Kodonas3

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite