Abstract

-

Objectives

This study fabricated and characterized a resolvin E1 (RvE1)-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) scaffold and determined its cytotoxicity and mineralization potential on inflamed human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs).

-

Methods

CMC scaffold incorporated with two concentrations of RvE1 (100 and 200 nM) was fabricated and characterized. The scaffolds’ porosity, drug release kinetics, and degradation were assessed. The impact of RvE1 on inflamed hDPSCs proliferation, proinflammatory gene expression (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]), alkaline phosphatase activity, and alizarin red S staining was evaluated.

-

Results

Scanning electron microscopy analysis demonstrated a highly porous interconnected microstructure. Release kinetics showed gradual RvE1 release peaking at day 14. Cumulative degradation of the CMC scaffold at 28 days was 57.35%. Inflamed hDPSCs exposed to 200 nM RvE1-CMC scaffold exhibited significantly improved viability compared to 100 nM. Both RvE1-CMC scaffolds significantly suppressed the expression of TNF-α at 7 days. Alkaline phosphatase activity was enhanced by both RvE1 concentrations on days 7 and 14. Alizarin red staining revealed superior mineralization potential of 200 nM RvE1 on days 14 and 21.

-

Conclusions

This study concludes 200 nM RvE1-CMC scaffold is a promising therapy for inflamed pulp conditions, enhancing cell proliferation and biomineralization potential in inflamed hDPSCs.

-

Keywords: Carboxymethyl chitosan; Dental pulp stem cells; Dentine regeneration; Pulp inflammation; Resolvin E1

INTRODUCTION

Dental pulp, a mesenchymal soft connective tissue, triggers an immune response when exposed to stimuli such as dental caries and trauma [

1] and demonstrates the ability to regulate pulp repair and regeneration by altering the immune response [

2]. Macrophages are abundant in pulp and are drawn to the area of inflammation. M1 macrophages dominate the inflammatory response and M2 phenotype predominates when inflammation reduces [

3]. The cessation of granulocyte recruitment along with macrophage differentiation at the site of tissue injury plays a crucial role in resolving inflammation and restoring tissue homeostasis [

4]. Temporal resolution of pulpal inflammation by altering mediators such as transforming growth factor beta-1, interleukin-1, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression (TNF-α) plays a pivotal role in maintaining tissue homeostasis [

1]. Currently, two therapeutic options are strategized for the repair/regeneration of inflamed pulp: (a) use of bioactive molecules that aid in sequestrated biomolecule release from dentin and (b) local drug delivery using bioactive molecules for repair and regeneration [

5].

Specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPM) are derived enzymatically from polyunsaturated fatty acids (arachidonic acid and omega-3 fatty acids) and aid in arresting acute inflammation with their pro-resolving, anti-inflammatory, and anti-infective properties [

6]. These advantages are considered for designing novel host-derived therapeutic strategies in clinical scenarios with inflammation. SPMs offer an advantage over corticosteroids, where the latter have been shown to inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators, enhance anti-inflammatory cytokine release, promote healing, but reduce host defense responses, hindering tissue repair [

7,

8].

Resolvin E1 (RvE1), a type of SPM with dual functions, is derived from the eicosapentaenoic acid pathway, inhibits transepithelial and transendothelial migration of neutrophils and stimulates phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by the macrophages, and shows enhanced pulpal and periodontal repair [

9,

10]. Topical application of RvE1 on inflamed pulp tissue in rat models limited the inflammatory cell infiltration compared to that of ethanol or corticosteroid application [

11]. Among the various concentrations tested, 100 nM of RVE1 (10, 100, and 200 nM) demonstrated an effective chemotactic effect on hDPSCs [

12]. Additionally, 100 nM RvE1 incorporated into collagen sponges has been shown to reduce necrosis rates and promote pulpal repair and reparative dentin formation in rat models with non-inflamed pulp [

12].

Currently, in literature, no established biomolecule delivery system exists for RvE1 in vital pulp therapy (VPT). Chitosan has gained attention as a drug delivery scaffold in dentistry [

13,

14]. However, modified chitosan, namely carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC), exhibits properties like calcium binding, high viscosity, and hydrodynamic volume [

15]. It enhances wound healing by regulating transforming growth factor beta-1, interleukin-1, and TNF-α expression [

16]. CMC, being a natural polymer, is used extensively in the field of regenerative medicine as a drug delivery scaffold due to its ability to support cell proliferation, its anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial effect, and ability to be fabricated into various scaffold designs such as films, sponges, hydrogels, etc [

17]. In a mouse air pouch inflammation model, combining resolvin D1 to chitosan scaffolds demonstrated a favorable healing response by modulating the inflammatory response and enhancing M2 polarization [

18]. This type of combination can aid in the sustained release of the drug. Currently, no literature exists to assess the effect of RvE1 addition to the CMC scaffold on inflamed human dental pulp cells.

Various drug delivery systems for VPT have shown promising results in tests on mineralization potential of human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs); however, they were tested on normal cells and did not mimic the clinical scenario of inflamed pulp. The anti-inflammatory potential of these systems remains underexplored, leaving the effectiveness of RvE1 with a scaffold in dental pulp inflammation unclear. The null hypothesis is RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold has no significant effect on the viability, anti-inflammatory marker expression, and odontogenic differentiation capacity of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated hDPSCs, compared to a CMC scaffold without RvE1.

The aim of this study is twofold: to fabricate and assess the characteristics of a CMC scaffold incorporated with RvE1, and to evaluate the role of RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold on the viability, expression of anti-inflammatory markers, and odontogenic differentiation ability of LPS-stimulated hDPSCs.

METHODS

Ethics approval

This study proposal was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of Meenakshi Ammal Dental College and Hospital, Chennai, India (No. MADC/IEC-I/24/2022). Each participant provided written consent prior to their involvement in the research.

RvE1 was procured from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), CMC from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), LPS from Sisco Research Laboratories (Maharashtra, India), and one-step qRT-PCR kit from DSS Takara Bio (New Delhi, India). Other chemicals were procured from HiMedia (Nashik, India) and Thermo Fisher Scientific Pvt, Ltd. (Mumbai, India).

Fabrication of carboxymethyl chitosan scaffold

A porous scaffold was prepared by dissolving CMC powder with a degree of substitution of 0.7, a degree of deacetylation of 85%, and a molecular weight of 250,000 Da in 2% acetic acid solution and freeze-dried at –20°C for 24 hours, followed by lyophilization at –80°C for 72 hours. After processing in 1N NaOH and sterilization in ethanol series (25%–70%), the scaffolds were washed, lyophilized, and sterilized with ultraviolet for 6 hours.

Incorporation of RvE1 in carboxymethyl chitosan scaffold

RvE1 was incorporated into sterile scaffolds using an embedding technique in a flow hood chamber to maintain a sterile environment. A solution of RvE1 in ethanol (water solubility: approximately 0.05 mg/mL at 25°C or phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with pH 7.2), with concentrations of 100 nM and 200 nM RvE1, was prepared in PBS (pH 7.2). A volume of 100-µL PBS containing 100 nM and 200 nM RvE1 was added dropwise with a micropipette into the respective scaffolds. RvE1 incorporated CMC scaffolds (CSR100 and CSR200) were lyophilized again (–80°C for 24 hours). The control group was prepared by adding 100 µL of PBS and lyophilized (CSPBS). All the prepared scaffolds were stored at –20°C until further use.

Morphological characterization

1. Porosity analysis

The microstructural analysis of samples of CSR100, CSR200, and CSPBS scaffolds was done using high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HRSEM) (FEI Quanta FEG 200), operating at 5 kV up to ×500 magnification. The mean pore dimensions of the scaffolds were established through direct geometric examination of the HRSEM images.

Physicochemical characterization

1. Release kinetics of carboxymethyl chitosan scaffolds with RvE1

The drug release kinetics of RvE1 from the lyophilized porous CMC scaffolds (CSR100 and CSR200) were analysed using Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry at various time intervals up to 28 days (1st, 4th, 8th, 12th, 16th, 20th, 24th hour, and days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28). Prior to the in vitro release of RvE1 assessment, a linear calibration curve of standard solution was constructed by measuring the absorbance at λ = 272 nm of different concentrations (10–250 nM) of RvE1. The 100 nM and 200 nM RvE1-loaded scaffolds were immersed in 2 mL Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS) (pH 7.2, at 37°C), separately. At defined time intervals, 1 mL of solution was withdrawn from each sample and replaced with an equivalent volume of fresh PBS. RvE1 was detected at 272 nm. Absorbance values of test samples were compared against the calibration curve to quantify the cumulative release.

2. In vitro biodegradation analysis

The sterile scaffolds were immersed in 2 mL of PBS with 10 mg/L of lysozyme (pH 6.24) and placed in an incubator at 37°C. The lysozyme was replenished every 3rd day. Controls were maintained in PBS without lysozyme. Scaffolds were removed at various time intervals up to 28 days (1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days). The scaffolds were lyophilized and weighed to determine dry weight. Degradation extent was calculated using the formula:

where, Wi = initial dry weight, Wf = final dry weight after degradation.

Human dental pulp stem cells isolation

Human dental pulp tissue was isolated from either normal impacted third mandibular molars or normal premolars extracted for orthodontic therapy from healthy patients (age, 14–20 years) with informed consent. Isolation of hDPSCs was done based on the methodology proposed in previous literature [

19]. In brief, hDPSCs were isolated by the enzymatic digestion method. They were extracted from human pulp tissues through treatment with collagenase type I (3 mg/mL) and dispase (4 mg/mL) and then seeded into 10-cm culture plates at low density (0.04 × 10

5/plate). Rapidly growing individual colonies were isolated and expanded with α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 µM L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. The medium was periodically changed every alternate day till the cells reached 80% confluency. A subculture was prepared with the aid of 0.2% trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and cells from passage 3 were phenotyped by flow cytometry for the following antibodies: anti-CD105-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-CD90-FITC, and anti-CD31-phycoerythrin were used in this study.

Cells were seeded at 60% to 80% confluency and cultured in α-MEM with or without LPS (Escherichia coli, 1 µg/mL) for 72 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2 and the medium was replenished every day.

The categories of experiment conducted to assess the effect of the fabricated RvE1-loaded scaffolds on normal and LPS-treated hDPSCs are tabulated in

Table 1. All the following experiments were performed in triplicate.

The viability of hDPSCs was quantitatively evaluated by measuring the reduction of tetrazolium salts to colored formazan products [

20]. About 5 × 10

4 cells were seeded onto the scaffold in 1 mL of cell medium and incubated at 37°C overnight to allow the cells to attach to the scaffold. At predetermined intervals of 7, 14 and 21 days, the culture medium was removed and 1,000 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) solution (5 mg/mL) was added to the wells and cultured at 37°C under 5% CO

2 for 4 hours and 1,000 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well to solubilize the crystals. Medium was changed every 2 days. Cell count was determined by measuring formazan absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader and visualized under an inverted microscope (×10 magnification).

hDPSCs treated with LPS and RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold were subjected to RNA isolation to evaluate the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. Cell lysis was performed, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent. It was then subjected to DNase treatment to remove any DNA contaminants. Agarose gel electrophoresis of RNA isolated from different groups is shown in

Supplementary Figure 1. RNA quantification was carried out using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and the extracted RNA was subjected to one-step qRT-PCR analysis to study the relative gene fold expression of TNF-α. The double Delta CT method was used for the calculation of the relative fold of expression for the gene of interest.

GAPDH was used as the housekeeping gene (reference gene) and the normalization of data was done using the same. The primer sequences are listed in

Table 2.

Initially, 5 × 10

4 hDPSCs were seeded onto each scaffold in 24-well culture plates and cultured up to 21 days. Adherent cells were lysed using 500 µL of lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton-X100 in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay buffer. After sonication for 5 minutes, samples were collected on days 7 and 14 post-odontogenic differentiation. Subsequently, the homogenized samples were centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 20 minutes to obtain the enzyme extract. Protein concentration of the enzyme extract is given in

Supplementary Table 1.

At 60% to 70% confluency, hDPSCs were induced to undergo odontoblastic differentiation upon exposure to odontogenic conditioned medium. To 960 µL of assay buffer, 20 µL of substrate (167 mM p-Nitrophenyl phosphate) was added and equilibrated at 37°C for 1 minute. Later, 20 µL of enzyme extract was added and mixed. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader.

Alizarin red S staining

Following odontoblastic conversion as described previously, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, rinsed with DPBS, stained with 1% alizarin red for 30 minutes at room temperature, rinsed with DPBS, and visualized under an inverted microscope (×20). For quantification of alizarin red staining, the stained cells were incubated with 10% acetic acid for 30 minutes, followed by centrifugation. The resulting supernatant was collected for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft 365; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Normality tests were conducted using the Shapiro-Wilk test, indicating normal distribution. Independent sample t-tests compared degradation analysis and release kinetics between groups, while paired t-tests assessed intragroup degradation. Tukey test post hoc was used for multiple internal comparisons MTT assay, ALP activity, and alizarin red staining. One-way analysis of variance was used to assess gene expression. Significance was set at 5% and performed using IBM SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

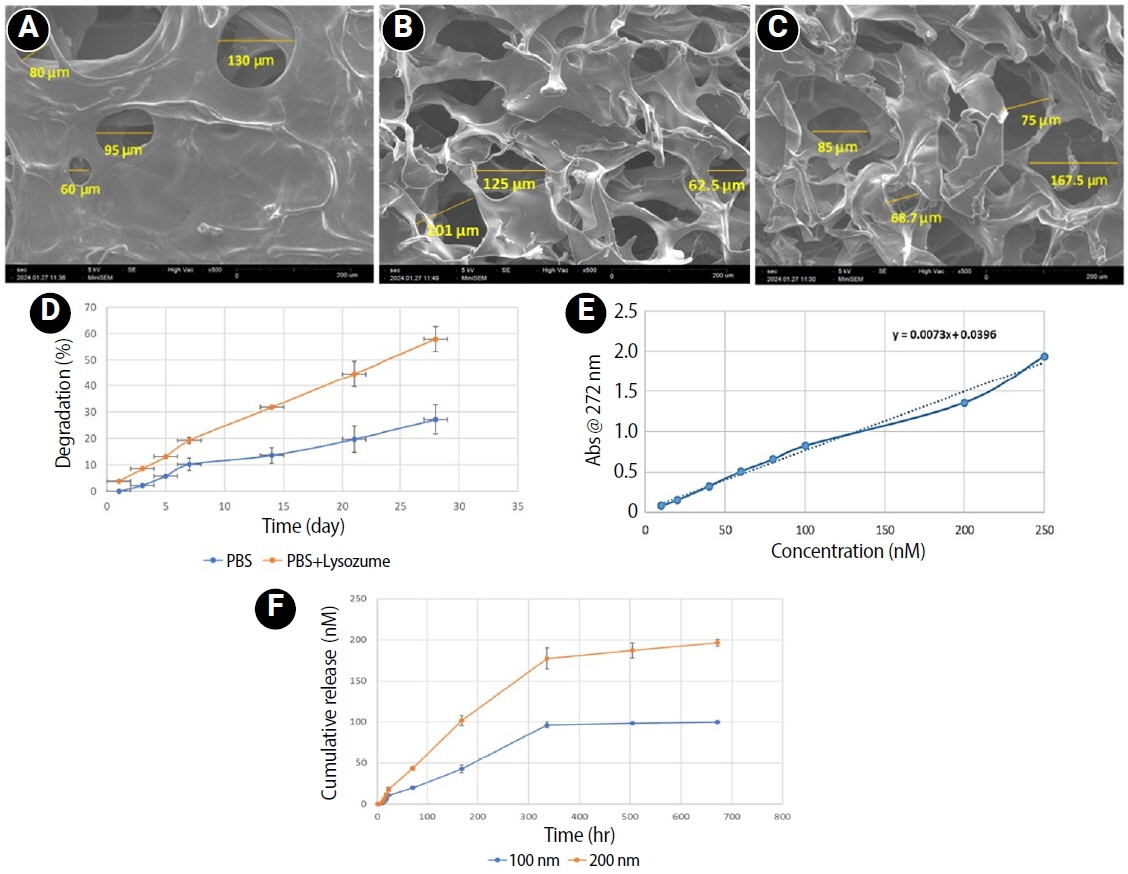

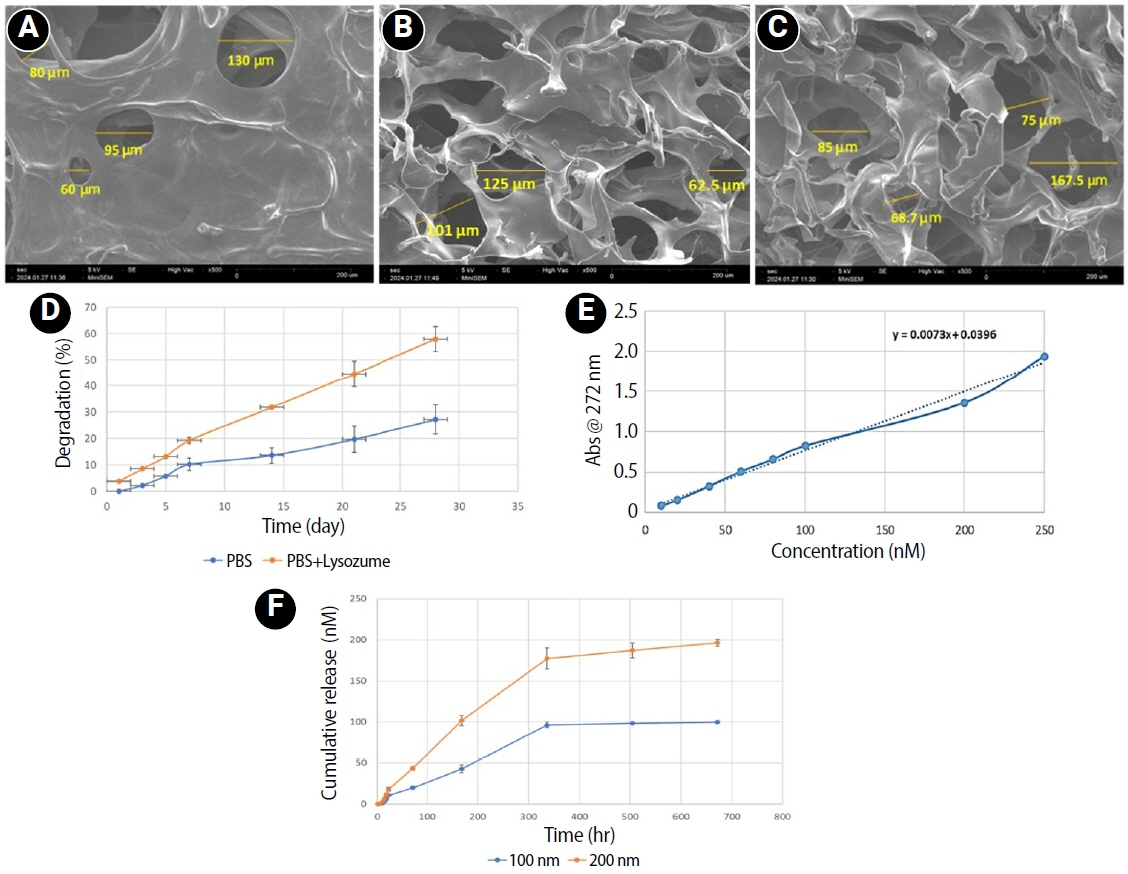

Morphological and physicochemical properties of the scaffolds

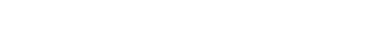

The microstructural analysis of scaffolds exhibited a highly porous, homogeneous structure characterized by interconnected pores. The mean pore diameters of CS

PBS, CSR

100, and CSR

200 are 91.25, 99.05, and 122.75 μm, respectively (

Figure 1A–

C). Degradation analysis showed that 44.61% of scaffold degraded in 3 weeks when exposed to lysozyme (

Figure 1D). The release profile of RvE1 demonstrated an initial gradual release of 42.95% and 50.92% from CSR

100 and CSR

200 scaffolds, respectively, by the end of the first week. This was followed by a rapid release phase, reaching 96.5% and 88.67% for CSR

100 and CSR

200, respectively, by day 14. Subsequently, the release plateaued, indicating a sustained but minimal release thereafter (

Figure 1F).

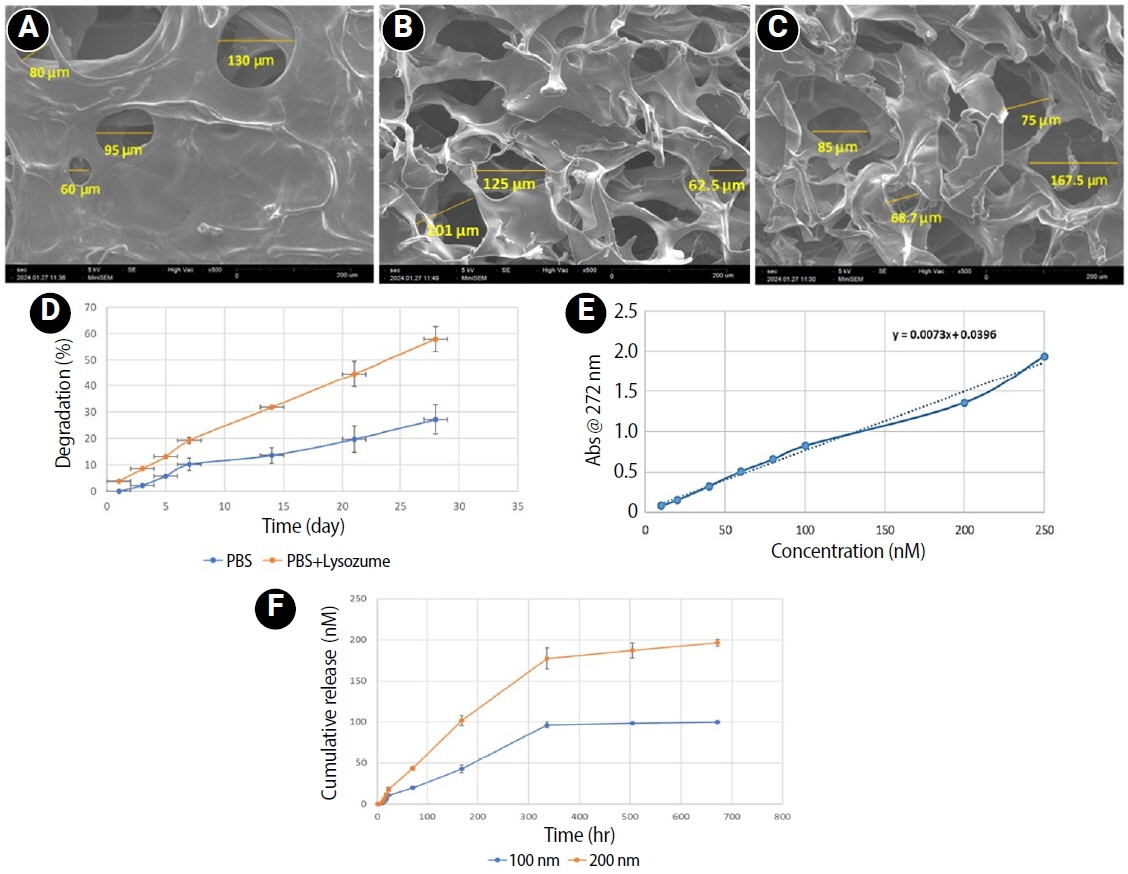

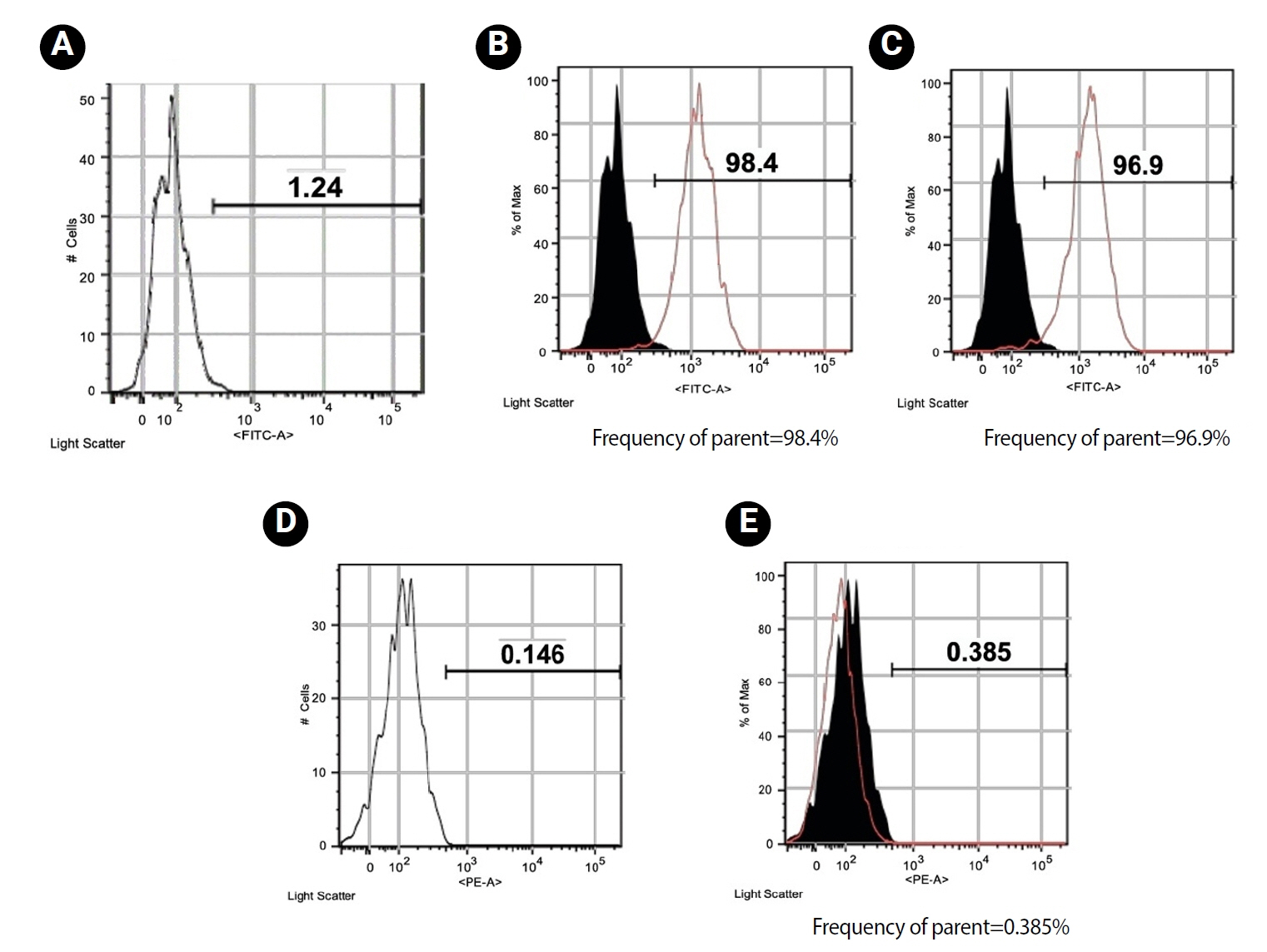

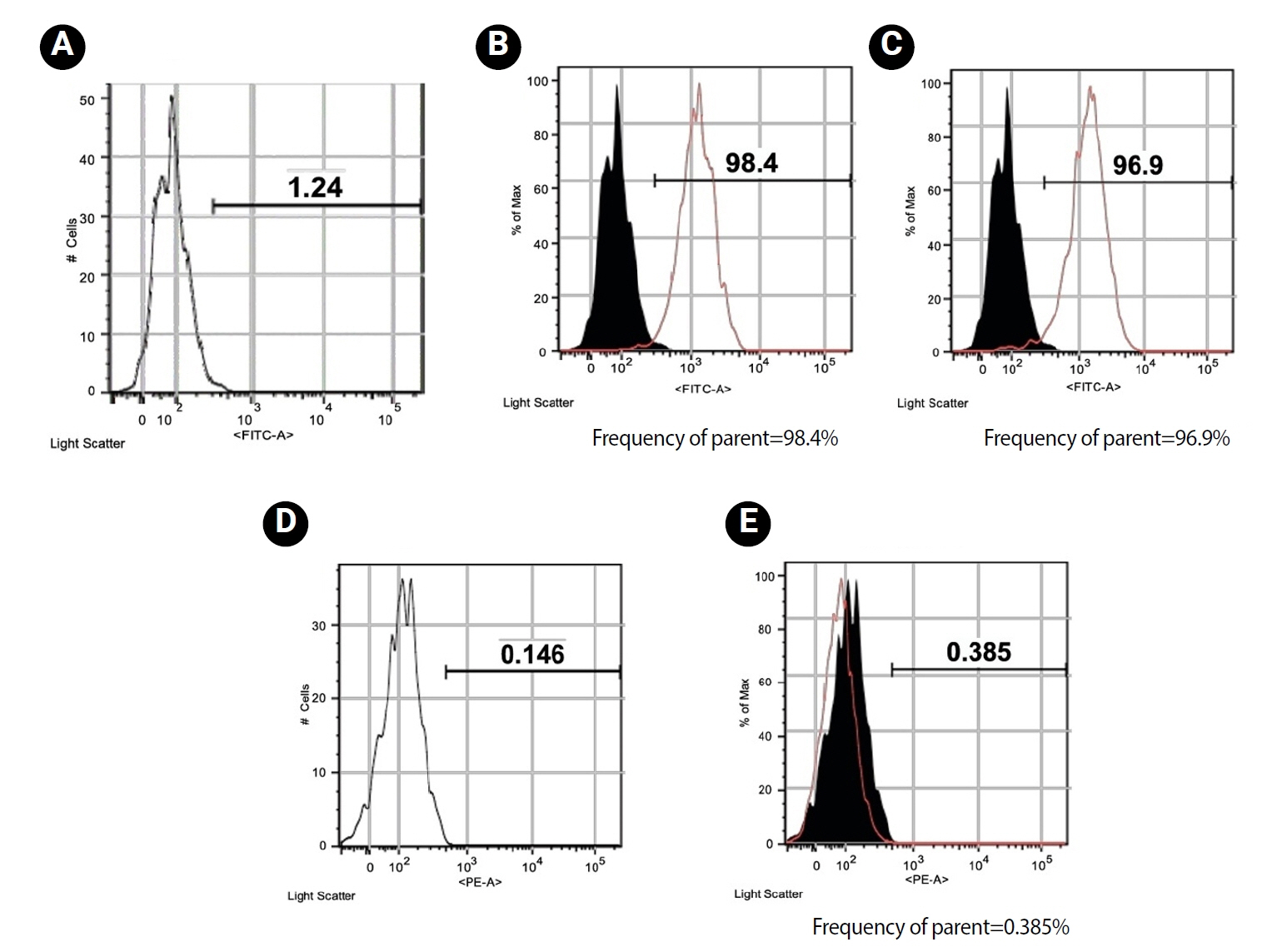

hDPSCs presented a typical homogeneous spindle morphology. Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that the hDPSCs used in this experiment were positive for mesenchymal cell surface markers CD105 (98.4%) (

Figure 2B) and CD90 (96.9%) (

Figure 2C), and negative for hematopoietic marker CD31 (0.385%) (

Figure 2E).

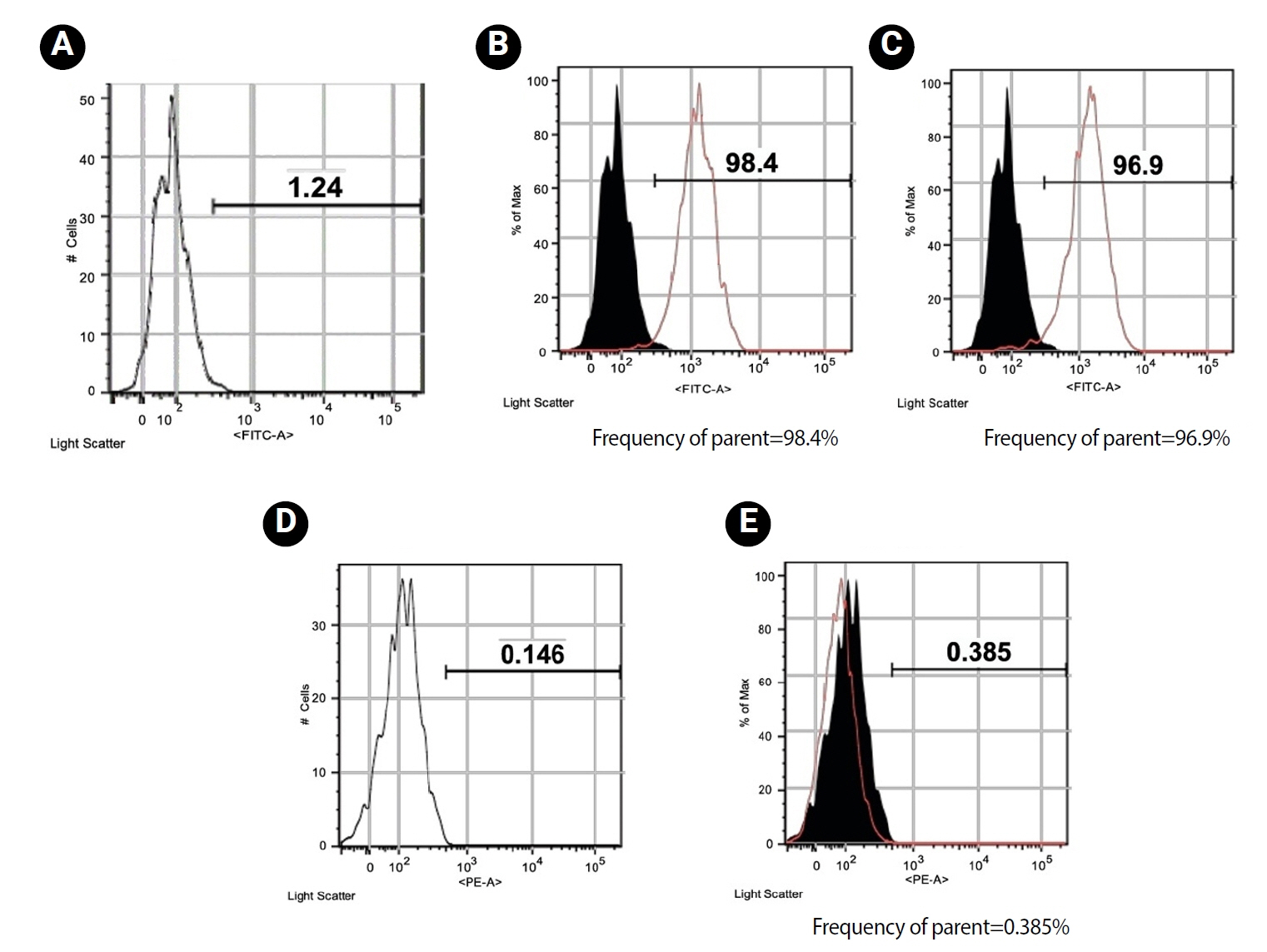

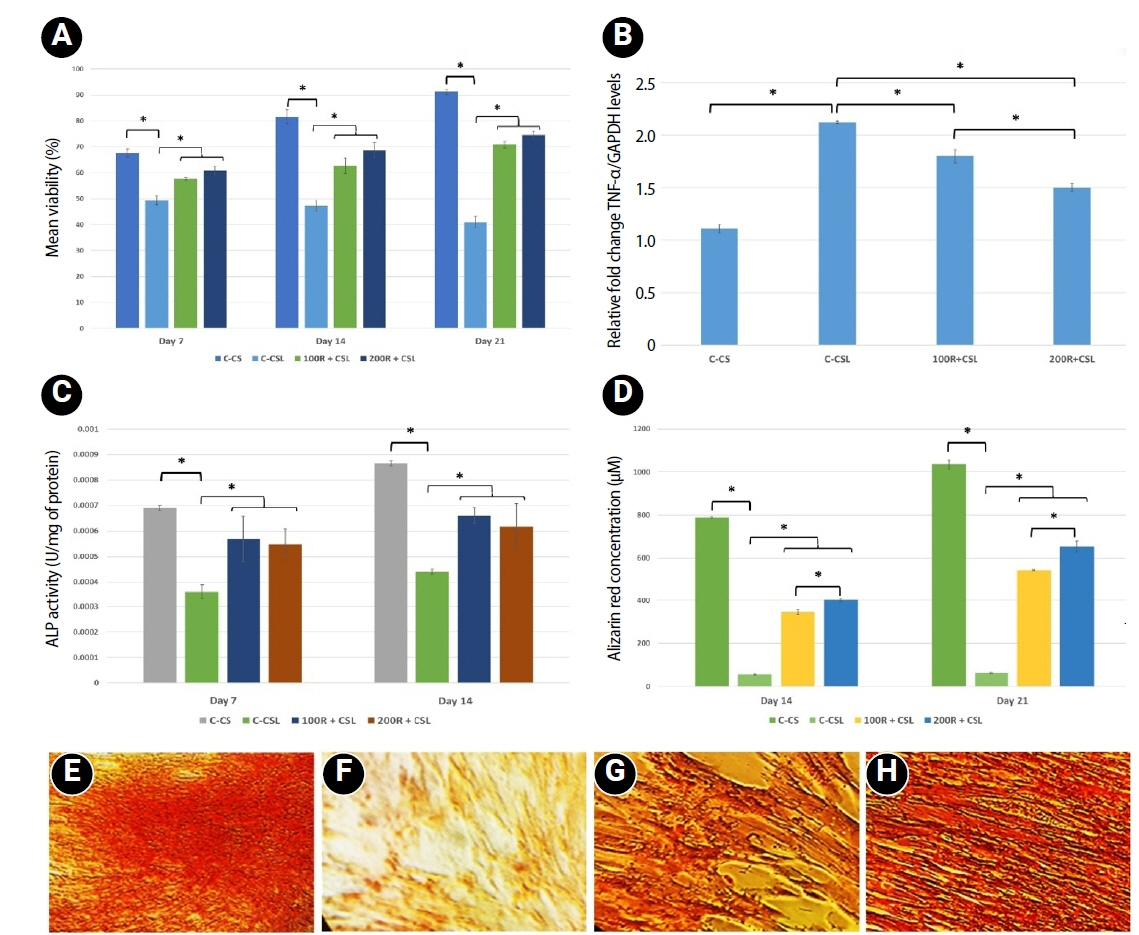

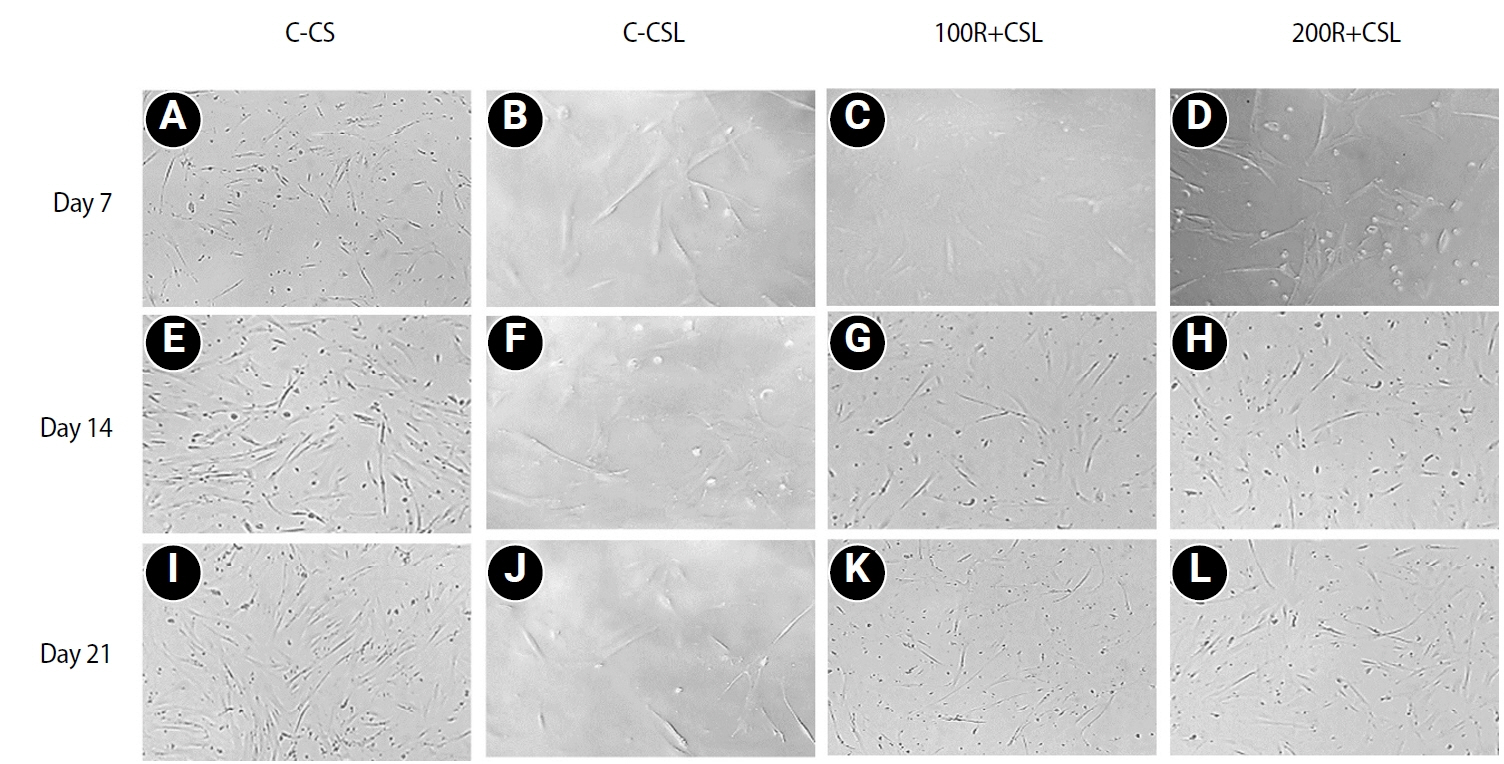

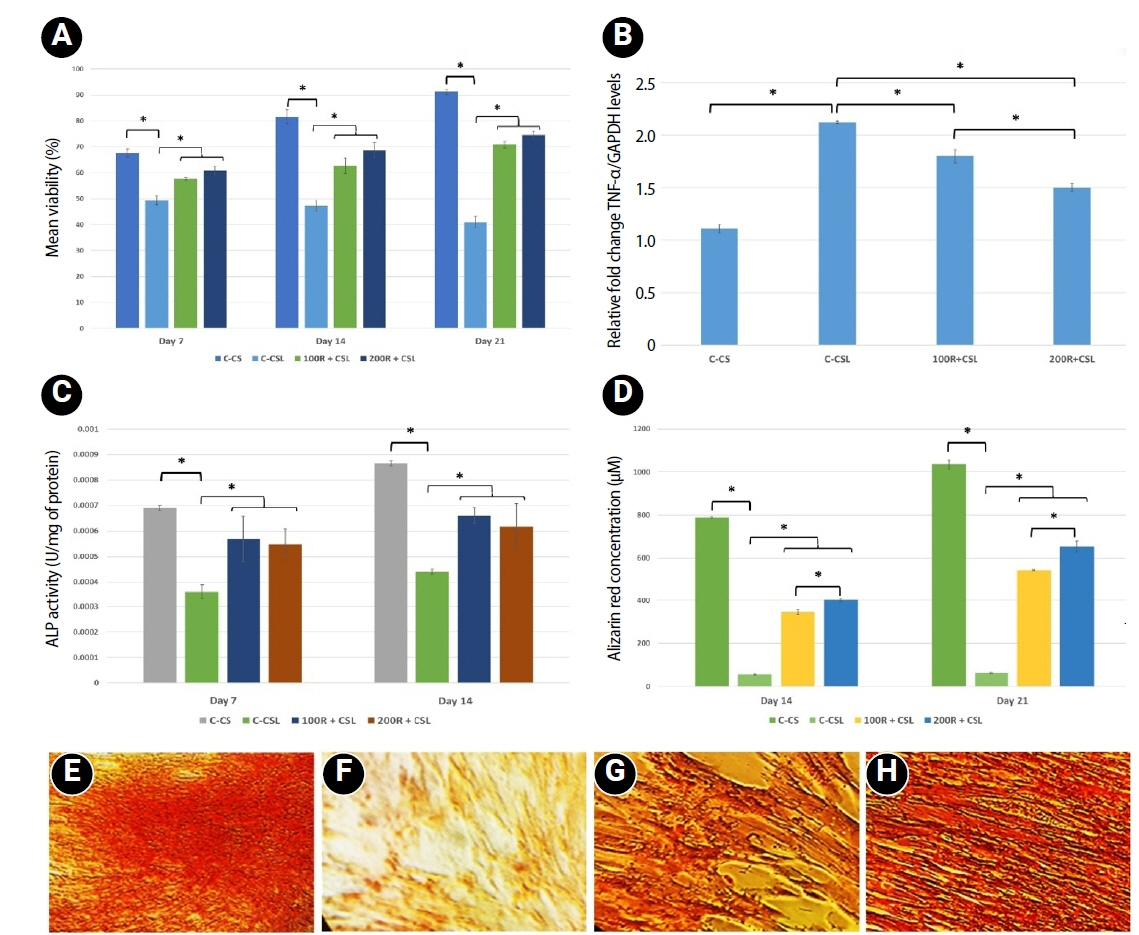

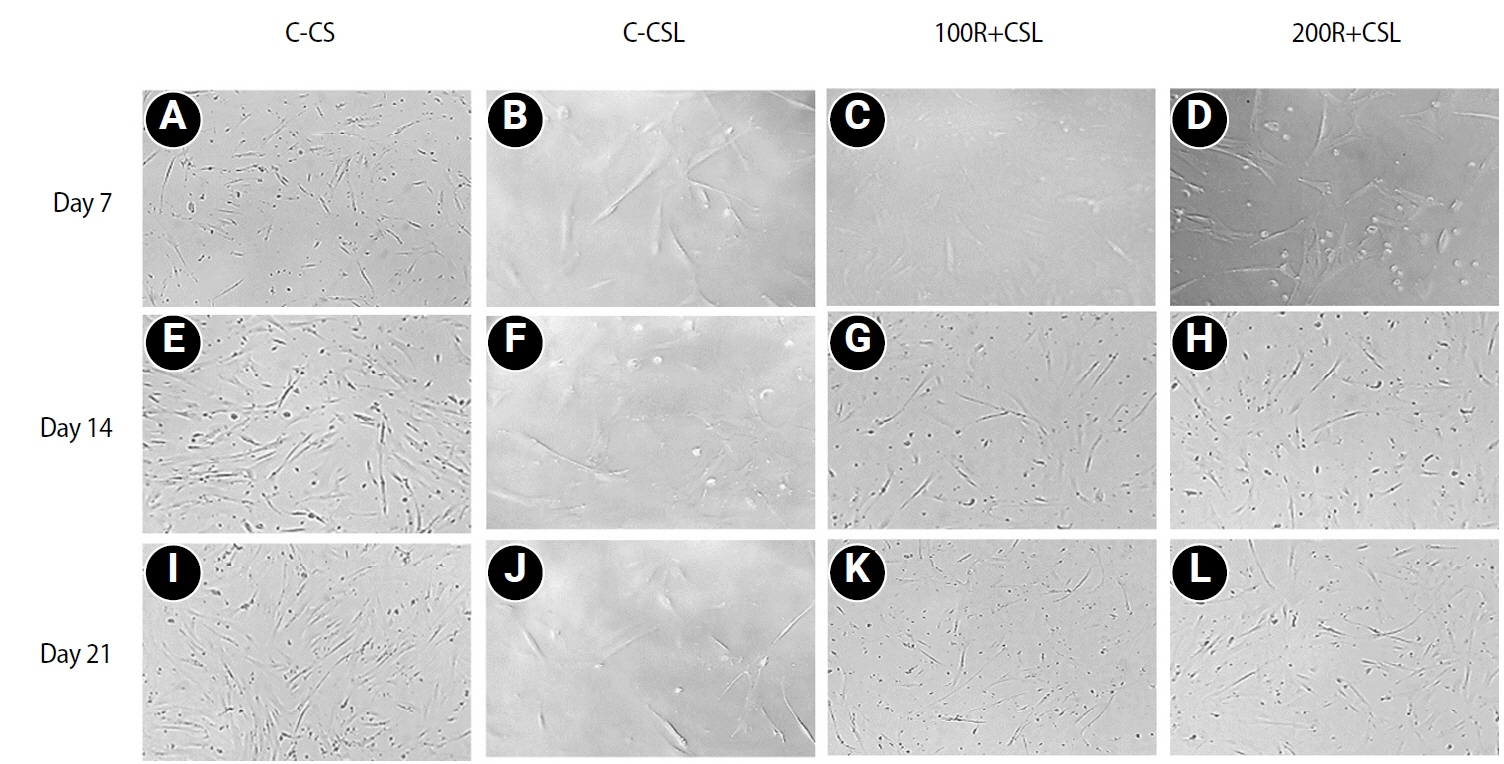

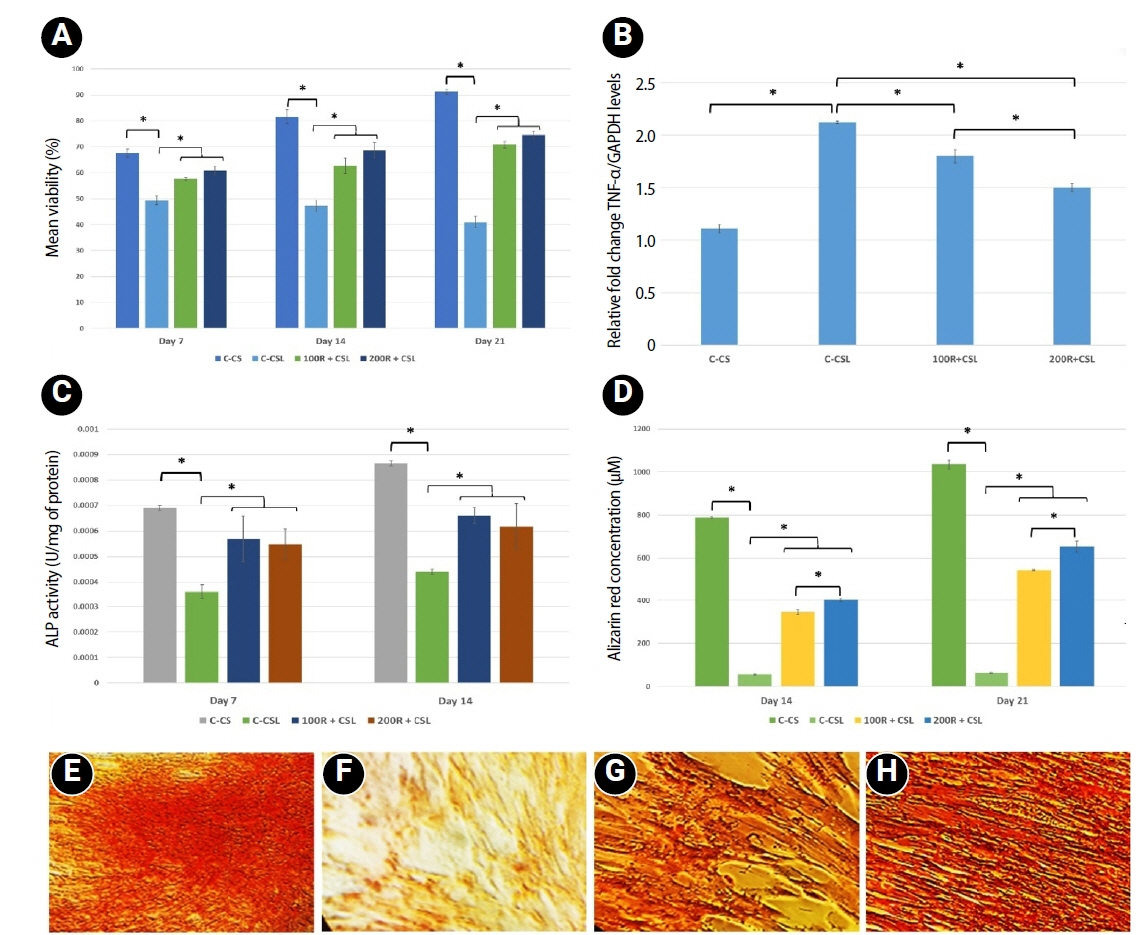

Loading of CMC with RvE1 at concentrations of 100 nM and 200 nM demonstrated biocompatibility, with no evidence of cytotoxicity and a sustained increase in cell proliferation up to 21 days. The cultured cells exhibited a homogeneous distribution and maintained a characteristic spindle-shaped morphology. Stimulation of inflammation with LPS resulted in a reduction in the viability of hDPSCs at all assessed time points. Treatment with RvE1 (100R + CSL and 200R + CSL) has shown a significant increase in cell proliferation at all time intervals compared to the inflamed C-CSL group (

p < 0.05) and there was no significant difference (

p > 0.05) between 100R + CSL and 200R+CSL groups in all time intervals (

Figures 3 and

4A).

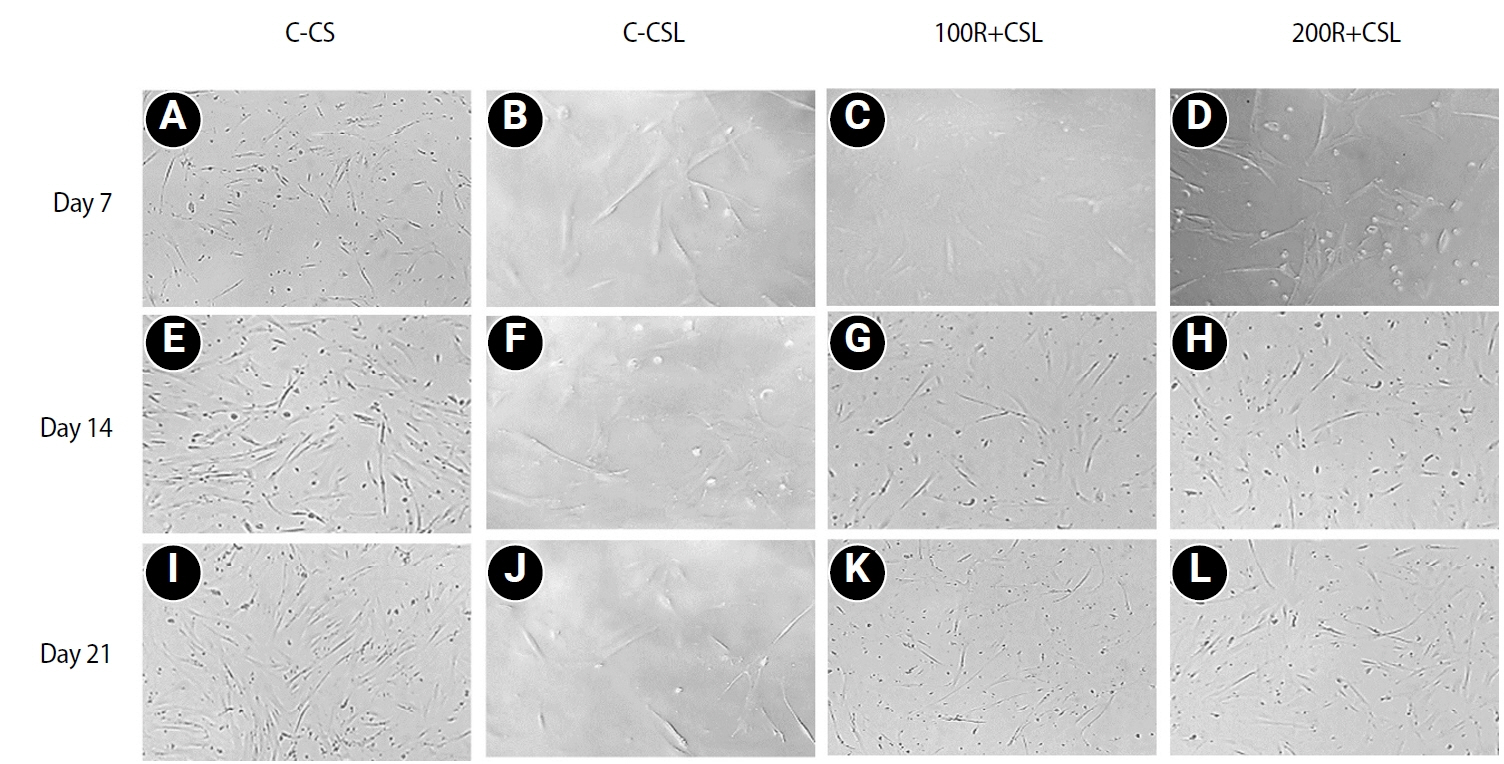

Treatment of hDPSCs with LPS increased the gene expression of TNF-α. Both (100 nM and 200 nM) concentrations of RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold significantly reduced the expression of TNF-α at 7 days, and 200R + CSL showed significantly lower expression of TNF-α than 100R + CSL group (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 4B).

ALP analysis and alizarin red S staining were performed to investigate the effect of RvE1-loaded CMC on the early and late biomineralization capability of LPS-stimulated hDPSCs.

1. Alkaline phosphatase activity

LPS-inflamed hDPSCs exhibited significantly reduced ALP activity compared to all other groups. Both 100 nM and 200 nM RvE1-loaded CMC scaffolds significantly enhanced ALP activity (

p < 0.05). Although the 100R + CSL group showed higher ALP levels than the 200R + CSL group on days 7 and 14, the difference between the two RvE1 concentrations was not statistically significant (

Figure 4C).

2. Alizarin red S staining

Alizarin red quantification showed that the non-inflamed group showed the highest biomineralization potential on day 21. Inducing inflammation with LPS has been shown to reduce the biomineralization ability of hDPSCs less than the non-inflamed group. RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold significantly enhanced the biomineralization potential in both concentrations on days 14 and 21 compared to the inflamed group. However, the 200 nM RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold had significantly higher biomineralization potential than the 100 nM RvE1 on days 14 and 21. Biomineralized nodules were found to be thicker and denser on treatment with 200 nM RvE1 than 100 nM on day 21 (

Figure 4D–

H).

DISCUSSION

Vital pulp management aims to deliver therapeutic options for the resolution of inflammation in pulp and create a conducive environment for repair. RvE1 interacts with ChemR23 receptors and decreases NF-κB activation in polymorphonuclear neutrophils, thereby reducing inflammation [

21,

22]. ChemR23 showed significant expression on hDPSCs, suggesting a potential therapeutic role [

12].

A concentration of 100 nM of RvE1 was selected based on evidence from a previous study [

12] and double the concentration was included for comparison in the current study. The scaffold’s degradation rate and release of biomolecules over time are influenced by its degree of crosslinking and porosity [

23]. In this study, SEM images illustrated a porous structure, which will provide more active sites for lysozyme to act upon, leading to adequate degradation and more efficient drug release. All three CMC scaffolds had a mean pore size in the range of 61.7–174 μm, which is comparable to that of previous studies (60–180 μm) [

24,

25]. Scaffolds with larger mean pore sizes of 65 and 145 μm demonstrated enhanced hDPSCs ingrowth and proliferation [

25].

In this study, maximum degradation and drug release occurred at 14 days, and 43% of the scaffold degraded in 21 days. This observation is similar to previous literature, where 40% of the scaffold degraded at 21 days [

26]. The initial slow drug release in this study could be attributed to the embedding technique followed by lyophilization which extends the release of RvE1 and negates its rapid degradation [

27] and increases the bioavailability over a prolonged time. In a previous study, a delayed and extended release over a period of 3 days was observed in the lyophilized chitosan + RvD1 scaffold compared to the non-lyophilized counterparts [

18].

LPS levels in infected root canals are observed in the range of 0.001–2 μg/mL [

28,

29] and inflamed pulpal conditions were simulated with 1 μg/mL LPS [

30]. However, in previous studies, stimulation with LPS did not significantly affect the proliferation [

30], but in contrast, this study showed a 40% survival rate for LPS-treated hDPSCs at 21 days. This can be attributed to the exposure time of up to 7 days in previous literature and up to 21 days in this study.

The CMC scaffold with 100 nM and 200 nM RvE1 showed biocompatibility and an increase in hDPSCs viability up to 21 days. A previous study demonstrated that direct application of 100 nM RvE1 on hDPSCs exhibited greater compatibility compared to 200 nM [

12]. In contrast, this study showed 200 nM to be more compatible (no significant difference from 100 nM). This could be attributed to the scaffold-based delivery of the drug to the cells in this study.

Treatment with RvE1-loaded CMC scaffolds led to a marked downregulation of TNF-α expression in a dose-dependent manner, indicating the anti-inflammatory efficacy of the bioactive scaffold system. TNF-α is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in initiating and orchestrating immune responses [

31,

32]. It induces the production of other cytokines, activates and upregulates adhesion molecules, and stimulates cellular proliferation [

31,

32]. By coordinating the early host response to tissue injury, TNF-α serves a critical regulatory role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and serves as a reliable and sensitive biomarker for assessing the severity and resolution of pulpal inflammation [

31,

32].

hDPSCs treatment with LPS reduced ALP activity, while co-treatment with RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold significantly improved it. On days 7 and 14, 100R + CSL and 200R + CSL showed similar ALP activity. RvE1 enhanced ALP activity by 1.5 times than inflamed hDPSCs, which was consistent with previous findings [

12].

Alizarin red staining results showed that on days 14 and 21, the 200R+CSL group exhibited 7- and 10-times higher mineralization compared to the inflamed hDPSCs. Qualitative analysis revealed denser and larger mineralization nodules at 21 days, indicating enhanced mineralization. These results suggest the potential of the RvE1-CMC scaffold in promoting odontoblast-like differentiation of hDPSCs, with varying effects observed between different concentrations and time points, thus enhancing the odontogenic differentiation. This synergism between RvE1 and CMC could be attributed to the activation of the ChemR23 signalling pathway by RvE1 [

21] as well as the biomimetic mineralization ability of CMC [

33]. ChemR23 is expressed in ameloblasts, odontoblasts, and osteoblasts [

34], and the Chemerin/ChemR23 signalling pathway is known to regulate the differentiation of ameloblasts and odontoblasts [

34]. RvE1 directly affects osteoblasts, reducing RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand) levels, which are elevated during inflammatory conditions, and increasing osteoprotegerin production [

35]. Furthermore, CMC exhibits enhanced physicochemical properties, including strong calcium-chelating capacity and the ability to induce biomimetic mineralization [

15,

33], and has shown synergistic mineralization effect when combined with nanohydroxyapatite [

36,

37].

The healing process post-VPT comprises four stages: exudative (1–5 days), proliferative (3–7 days), osteodentin formative (5–14 days), and tubular dentin formative (>14 days) [

38]. Macrophages are abundant in pulp, especially in the first 5–7 days of inflammation [

39]. The increased RvE1 release at 7–14 days, accompanied by TNF-α suppression, can be advantageous by enhancing (a) macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 and (b) odontogenic differentiation during the odontogenic formative stage. This study suggests 200 nM RvE1 with a CMC scaffold as a potential clinical drug delivery system to be studied further.

The strength of this study is inducing inflammation in hDPSCs mimicking inflamed clinical conditions. The future research will be focused on assessing the other inflammatory and biomineralization markers for dentin and translating them into animal studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the limitations of this study, the RvE1-loaded CMC scaffold was not toxic to the inflamed hDPSCs and 200 nM RvE1 has superior cell proliferation ability and biomineralization capacity of inflamed hDPSCs. This scaffold holds promise as a novel therapeutic strategy for alleviating pulp inflammation and promoting dentin-pulp regeneration.

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

-

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. Prashanth K K and his team from Simbioen Labs (Chennai, India) for helping us execute this study and their meticulous assistance. We wish to inform you that this study was previously presented at the 22nd European Society of Endodontology Paris Conference, 2025. Furthermore, the conference abstract will be published in the International Endodontic Journal. This disclosure is provided to ensure transparency and proper acknowledgment of prior dissemination.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Investigation: Suresh N, Balasubramanian HP, Koteeswaran V. Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology: Balasubramanian HP, Suresh N. Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization: Balasubramanian HP. Project administration, Software: all authors. Supervision, Validation: Suresh N, Koteeswaran V, Natanasabapathy V. Writing - original draft: Balasubramanian HP. Writing - review & editing: Suresh N, Koteeswaran V, Natanasabapathy V. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The datasets are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Figure 1.Physicochemical properties of the scaffolds. (A–C) Scaffold morphology observed under scanning electron microscopy showing a porous structure: (A) CSPBS, (B) CSR100, and (C) CSR200. (D) Scaffold degradation (%) in the presence of PBS and PBS with lysozyme. (E, F) Release kinetics of resolvin E1 (RvE1): (E) standard curve showing absorbance of different RvE1 concentrations under ultraviolet spectroscopy; (F) cumulative release profile of RvE1 (nM) from CSR100 and CSR200 scaffolds. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Figure 2.Figure 2. Flow cytometric analysis of mesenchymal stem antigens in human dental pulp stem cells. (A) Isotype control for FITC staining showing minimal expression; (B) CD105 expression; (C) CD90 expression; (D) Isotype control for PE staining showing minimal expression; (E) CD31 expression (negative). FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

Figure 3.Representative inverted microscopic views (×10) of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1. (A–D) Day 7 cell morphology of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1. (E–H) Day 14 cell morphology of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1. (I–L) Day 21 cell morphology of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; hDPSCs, human dental pulp stem cells; CMC, carboxymethyl chitosan; RvE1, resolvin E1. Abbreviations of experimental groups (C-CS, C-CSL, 100R + CSL, and 200R + CSL) are defined in Table 1.

Figure 4.Effects of RvE1 on LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs. (A) Mean cell viability (%) of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1 at days 7, 14, and 21. (B) Expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1 at day 7. (C) Mean ALP activity (units/mg protein) of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1 at days 7 and 14. (D) Mean alizarin red staining quantification (µM) of LPS- and non-LPS-treated hDPSCs cultured with CMC scaffolds loaded with or without 100 and 200 nM RvE1 at days 14 and 21. (E–H) Representative alizarin red staining images (×20) at day 21: (E) C-CS, (F) C-CSL, (G) 100R + CSL, and (H) 200R + CSL. RvE1, resolvin E1; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; hDPSC, human dental pulp stem cell; CMC, carboxymethyl chitosan; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; ALP, alkaline phosphatase. hDPSC, human dental pulp stem cell; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; ALP, alkaline phosphatase. Abbreviations of experimental groups (C-CS, C-CSL, 100R + CSL, and 200R + CSL) are defined in

Table 1.

*p < 0.05, significant difference between the groups.

Table 1.Different study groups and abbreviations

|

Group |

Description |

Abbreviation |

|

Non-inflamed groups |

CSPBS seeded with 5 × 104 hDPSCs |

C-CS |

|

Inflamed groups |

CSPBS seeded with 5 × 104 LPS-treated hDPSCs |

C-CSL |

|

CSR100 seeded with 5 × 104 LPS-treated hDPSCs |

100R + CSL |

|

CSR200 seeded with 5 × 104 LPS-treated hDPSCs |

200R + CSL |

Table 2.Specific primer sequences for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

|

No. |

Gene |

Forward primer |

Reverse primer |

|

1 |

GAPDH

|

TGTTCGTCATGGGTGTGAAC |

ATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCAT |

|

2 |

TNF-α

|

TAGCCATGTTGTAGCAAACCC |

TTATCTCTCAGCTCCACGCCA |

REFERENCES

- 1. Galler KM, Weber M, Korkmaz Y, Widbiller M, Feuerer M. Inflammatory response mechanisms of the dentine-pulp complex and the periapical tissues. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:1480.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Cooper PR, Holder MJ, Smith AJ. Inflammation and regeneration in the dentin-pulp complex: a double-edged sword. J Endod 2014;40:S46-S51.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Locati M, Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophage activation and polarization as an adaptive component of innate immunity. Adv Immunol 2013;120:163-184.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Campbell EL, Louis NA, Tomassetti SE, Canny GO, Arita M, Serhan CN, et al. Resolvin E1 promotes mucosal surface clearance of neutrophils: a new paradigm for inflammatory resolution. FASEB J 2007;21:3162-3170.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Komabayashi T, Zhu Q, Eberhart R, Imai Y. Current status of direct pulp-capping materials for permanent teeth. Dent Mater J 2016;35:1-12.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 2014;510:92-101.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Tsianakas A, Varga G, Barczyk K, Bode G, Nippe N, Kran N, et al. Induction of an anti-inflammatory human monocyte subtype is a unique property of glucocorticoids, but can be modified by IL-6 and IL-10. Immunobiology 2012;217:329-335.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Koedam JA, Smink JJ, van Buul-Offers SC. Glucocorticoids inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor expression in growth plate chondrocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002;197:35-44.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol 2005;6:1191-1197.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Balta MG, Loos BG, Nicu EA. Emerging concepts in the resolution of periodontal inflammation: a role for resolvin E1. Front Immunol 2017;8:1682.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Dondoni L, Scarparo RK, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE, Figueiredo JA, Batista EL. Effect of the pro-resolution lipid mediator resolvin E1 (RvE1) on pulp tissues exposed to the oral environment. Int Endod J 2014;47:827-834.PubMed

- 12. Chen J, Xu H, Xia K, Cheng S, Zhang Q. Resolvin E1 accelerates pulp repair by regulating inflammation and stimulating dentin regeneration in dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021;12:75.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 13. Leonor IB, Baran ET, Kawashita M, Reis RL, Kokubo T, Nakamura T. Growth of a bonelike apatite on chitosan microparticles after a calcium silicate treatment. Acta Biomater 2008;4:1349-1359.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Pighinelli L, Kucharska M. Chitosan-hydroxyapatite composites. Carbohydr Polym 2013;93:256-262.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Chen XG, Park HJ. Chemical characteristics of O-carboxymethyl chitosans related to the preparation conditions. Carbohydr Polym 2003;53:355-359.Article

- 16. Peng S, Liu W, Han B, Chang J, Li M, Zhi X. Effects of carboxymethyl-chitosan on wound healing in vivo and in vitro. J Ocean Univ China 2011;10:369-378.ArticlePDF

- 17. Fonseca-Santos B, Chorilli M. An overview of carboxymethyl derivatives of chitosan: their use as biomaterials and drug delivery systems. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2017;77:1349-1362.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Vasconcelos DP, Costa M, Amaral IF, Barbosa MA, Águas AP, Barbosa JN. Development of an immunomodulatory biomaterial: using resolvin D1 to modulate inflammation. Biomaterials 2015;53:566-573.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Perry BC, Zhou D, Wu X, Yang FC, Byers MA, Chu TM, et al. Collection, cryopreservation, and characterization of human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells for banking and clinical use. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2008;14:149-156.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983;65:55-63.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Arita M, Ohira T, Sun YP, Elangovan S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 selectively interacts with leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and ChemR23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol 2007;178:3912-3917.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Samson M, Edinger AL, Stordeur P, Rucker J, Verhasselt V, Sharron M, et al. ChemR23, a putative chemoattractant receptor, is expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages and is a coreceptor for SIV and some primary HIV-1 strains. Eur J Immunol 1998;28:1689-1700.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Kim H, Kim HW, Suh H. Sustained release of ascorbate-2-phosphate and dexamethasone from porous PLGA scaffolds for bone tissue engineering using mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 2003;24:4671-4679.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Baskar K, Saravana Karthikeyan B, Gurucharan I, Mahalaxmi S, Rajkumar G, Dhivya V, et al. Eggshell derived nano-hydroxyapatite incorporated carboxymethyl chitosan scaffold for dentine regeneration: a laboratory investigation. Int Endod J 2022;55:89-102.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 25. Zhang Q, Yuan C, Liu L, Wen S, Wang X. Effect of 3-dimensional collagen fibrous scaffolds with different pore sizes on pulp regeneration. J Endod 2022;48:1493-1501.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Bellamy C, Shrestha S, Torneck C, Kishen A. Effects of a bioactive scaffold containing a sustained transforming growth factor-β1-releasing nanoparticle system on the migration and differentiation of stem cells from the apical papilla. J Endod 2016;42:1385-1392.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Mitchell S, Thomas G, Harvey K, Cottell D, Reville K, Berlasconi G, et al. Lipoxins, aspirin-triggered epi-lipoxins, lipoxin stable analogues, and the resolution of inflammation: stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13:2497-2507.PubMed

- 28. Jacinto RC, Gomes BP, Shah HN, Ferraz CC, Zaia AA, Souza-Filho FJ. Quantification of endotoxins in necrotic root canals from symptomatic and asymptomatic teeth. J Med Microbiol 2005;54:777-783.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Martinho FC, Chiesa WM, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC, Almeida JF, Souza-Filho FJ, et al. Comparison of endotoxin levels in previous studies on primary endodontic infections. J Endod 2011;37:163-167.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Xu F, Qiao L, Zhao Y, Chen W, Hong S, Pan J, et al. The potential application of concentrated growth factor in pulp regeneration: an in vitro and in vivo study. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019;10:134.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 31. Elsalhy M, Azizieh F, Raghupathy R. Cytokines as diagnostic markers of pulpal inflammation. Int Endod J 2013;46:573-580.ArticlePubMed

- 32. Hehlgans T, Pfeffer K. The intriguing biology of the tumour necrosis factor/tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily: players, rules and the games. Immunology 2005;115:1-20.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Wang R, Guo J, Lin X, Chen S, Mai S. Influence of molecular weight and concentration of carboxymethyl chitosan on biomimetic mineralization of collagen. RSC Adv 2020;10:12970-12981.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Ohira T, Spear D, Azimi N, Andreeva V, Yelick PC. Chemerin-ChemR23 signaling in tooth development. J Dent Res 2012;91:1147-1153.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 35. El Kholy K, Freire M, Chen T, Van Dyke TE. Resolvin E1 promotes bone preservation under inflammatory conditions. Front Immunol 2018;9:1300.PubMedPMC

- 36. Saravana Karthikeyan B, Madhubala MM, Rajkumar G, Dhivya V, Kishen A, Srinivasan N, et al. Physico-chemical and biological characterization of synthetic and eggshell derived nanohydroxyapatite/carboxymethyl chitosan composites for pulp-dentin tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;271:132620.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Gurucharan I, Saravana Karthikeyan B, Mahalaxmi S, Baskar K, Rajkumar G, Dhivya V, et al. Characterization of nano-hydroxyapatite incorporated carboxymethyl chitosan composite on human dental pulp stem cells. Int Endod J 2023;56:486-501.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 38. Yamamura T. Differentiation of pulpal cells and inductive influences of various matrices with reference to pulpal wound healing. J Dent Res 1985;64 Spec No:530-540.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 39. Mjör IA, Dahl E, Cox CF. Healing of pulp exposures: an ultrastructural study. J Oral Pathol Med 1991;20:496-501.ArticlePubMed

, Nandini Suresh,*

, Nandini Suresh,* , Vishnupriya Koteeswaran

, Vishnupriya Koteeswaran , Velmurugan Natanasabapathy

, Velmurugan Natanasabapathy

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite