Abstract

-

Objectives

The study aimed to investigate how environmental conditions impact the setting time and microhardness of premixed calcium silicate-based sealers.

-

Methods

The setting time and microhardness of three sealers (Endoseal MTA [MARUCHI], One-Fil [MEDICLUS], and Well-Root ST [VERICOM]) were evaluated under four environmental conditions: unsoaked, distilled water-soaked, phosphate-buffered saline-soaked, and pH 5-soaked gypsum molds (n = 12/group/condition). The setting time was measured with Gilmore needles, and microhardness was assessed using a Vickers tester after 3 days. Welch’s analysis of variance and Games-Howell post hoc tests were used for statistical analysis.

-

Results

The sealer type and environmental conditions significantly influenced setting time and microhardness (p < 0.001). The initial and final setting times were the shortest in the unsoaked samples. For Endoseal MTA and One-Fil, the unsoaked condition exhibited significantly shorter setting times than the soaked conditions. Well-Root ST exhibited significantly longer setting times in acidic conditions. Surface microhardness was highest in the unsoaked group (p < 0.001). Among the soaked groups, the phosphate-buffered saline-soaked group had the lowest hardness for Endoseal MTA, whereas the pH 5-soaked group exhibited the lowest hardness for One-Fil and Well-Root ST. Endoseal MTA consistently demonstrated a lower microhardness than the other sealers (p < 0.001).

-

Conclusions

Moisture, pH, and solution chemistry influenced the setting time and microhardness of premixed calcium silicate sealers. Although acidic conditions generally prolong the setting time and reduce hardness, the effects vary based on the sealers used and the setting environment.

-

Keywords: Calcium silicate; Dental cements; Hardness; Hydrogen-ion concentration; Humidity

INTRODUCTION

The microbiological objectives of endodontic treatment include eliminating bacteria from the root canal system and sealing all the entry and exit points. Antimicrobial interventions, such as chemomechanical procedures and intracanal medications, ensure bacterial elimination, whereas root canal obturation primarily accomplishes a hermetic seal [

1]. Endodontic sealers encapsulate residual bacteria by sealing the dentinal tubules, thus preventing reinfection of the root canal [

2]. Commonly used sealers include zinc oxide-eugenol, calcium hydroxide, glass ionomers, resin-based epoxy resins, methacrylate resin, and calcium silicate-based sealers (CSBSs) [

3]. CSBSs are typically formulated using synthetic calcium silicate, Portland cement, or mineral trioxide aggregates (MTA) [

4].

MTA, such as ProRoot MTA (Dentsply, Tulsa, OK, USA), a type of calcium silicate cement, is recognized for its favorable clinical outcomes. Initially developed as a root-end filling material, MTA has been applied in pulp capping, pulpotomy, apexogenesis, apical barrier formation in teeth with open apices, root perforation repairs, and root canal filling. The effectiveness of MTA has been ascribed to its superior sealing ability, antibacterial properties, and biocompatibility. It exhibits high pH, prolonged setting time, and low compressive strength [

5,

6]. Following the successful outcomes attributed to the use of MTA, calcium silicate-based materials are increasingly being used as sealers in root canal procedures. Unlike conventional sealers, CSBSs are hydraulic and hygroscopic, and require water to initiate a distinctive setting process [

4]. Premixed and injectable sealers are considered user-friendly; they remain unset in syringes and undergo setting reactions only upon exposure to aqueous environments [

7].

The physical properties of sealers, including setting time, flow, radiopacity, solubility, dimensional stability, and pH change, have been evaluated in previous studies [

8,

9]. Variations in the setting times were reported and were influenced by the study design. High pH and flowability have been observed, facilitating effective sealer distribution within root canal anatomical variants [

4]. Calcium silicate-based materials are recognized for their exceptional biocompatibility, bioactive properties, antibacterial effects, and low solubility, with excellent sealing and setting capabilities in humid environments [

10,

11]. Environmental conditions can also influence these properties. A significant delay in the setting time has been noted in the absence of sufficient moisture [

12,

13]. Sealers rely on moisture within the dentinal tubules, which varies in quantity, to initiate and complete the setting reaction [

7]. An unset or partially set sealer may permit rapid penetration of irritants, such as bacteria or bacterial byproducts, following obturation [

2].

During canal obturation, sealers are exposed to fluids near the apex, where adjacent tissues may exhibit normal or acidic pH owing to infection or inflammation [

14]. In other studies, exposure to an acidic environment reduced the microhardness of MTA and MTA-like materials [

15]. Moreover, CSBS exhibits a lower microhardness when exposed to both acidic and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) conditions, with acidic conditions having a more pronounced effect [

16].

According to the ISO 6876/2012 standards, a dental plaster mold with a cavity of 1 mm in height and 10 mm in diameter is recommended for materials requiring moisture for the setting reaction. Some studies have used dental plaster molds; however, most of these studies focused primarily on humid environments [

12,

17,

18] In this study, gypsum-molded specimens were exposed to PBS, which simulates the ionic composition of tissue fluids by providing phosphate ions and maintaining a stable, near-neutral pH through its buffering capacity, as well as to an acidic solution at pH 5 (hydrochloric acid), representing the chemical environments of healthy and inflamed periapical tissues, respectively. These varying conditions are expected to distinctly affect the setting behavior and properties of CSBSs.

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of environmental conditions on the initial and final setting times and the microhardness of three premixed calcium silicate-based root canal sealers. The null hypotheses were as follows: (i) No differences exist in the setting time or microhardness among the sealers. (ii) Moisture does not affect the setting time or microhardness of the sealers. (iii) pH changes do not affect the setting time or microhardness of the sealers.

METHODS

Specimen preparation

Three commercially available premixed CSBSs, Endoseal MTA (MARUCHI, Wonju, Korea), One-Fil (MEDICLUS, Cheongju, Korea), and Well-Root ST (VERICOM, Chuncheon, Korea), were evaluated. The chemical compositions of the sealers are listed in

Table 1. All samples were analyzed before the manufacturers’ specified expiration dates.

According to the ISO 6876:2012 standards, dental plaster molds with an internal diameter of 10 mm and a height of 1 mm were used for evaluating sealers requiring moisture for the setting reaction. The molds in the initial group for each material were maintained at 37°C and 100% relative humidity for 24 hours, following ISO standards, and served as the control group (unsoaked mold, US). Additional molds were exposed to distilled water [DW] (DW-soaked mold, DW), PBS at pH 7.4 (PBS-soaked mold, PBS), or hydrochloric acid (HCl) at pH 5 (pH 5-soaked mold, pH 5). The sealers and the setting environment conditions are summarized in

Table 2. The pH was measured using a calibrated pH meter (WTW, Inolab pH7110; Weilheim, Germany) with buffer solutions (pH 4, 7, and 10). The room temperature during measurements was maintained at 25°C. Each mold was individually immersed in a plastic flask containing 40 mL of the respective solutions and stored at 100% relative humidity and 37°C for 24 hours (

n = 12/group/condition).

Sealers were injected into the molds and stored at 100% relative humidity and 37°C. For the PBS-soaked and pH 5-soaked groups, a 40-µL drop of the respective solution was applied to stimulate sustained direct exposure to these fluids, which may be encountered in clinical inflammatory conditions or post-irrigation environments, followed by an overhead projector film. For the DW group, no additional drops were used, as exposure to ≥95% relative humidity in a water bath is generally accepted to provide adequate environmental moisture for setting without excess surface liquid. A glass plate was placed over the sealer to ensure a flat and uniform surface.

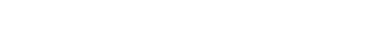

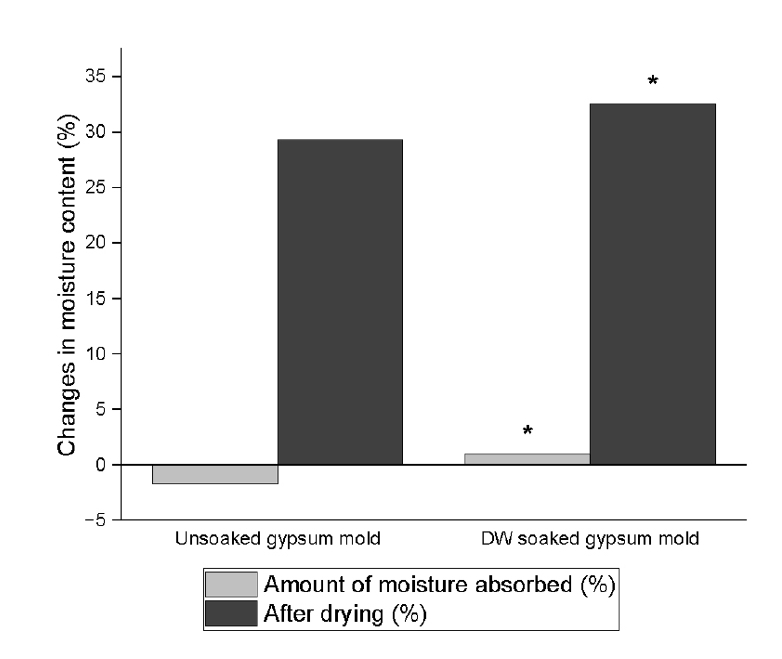

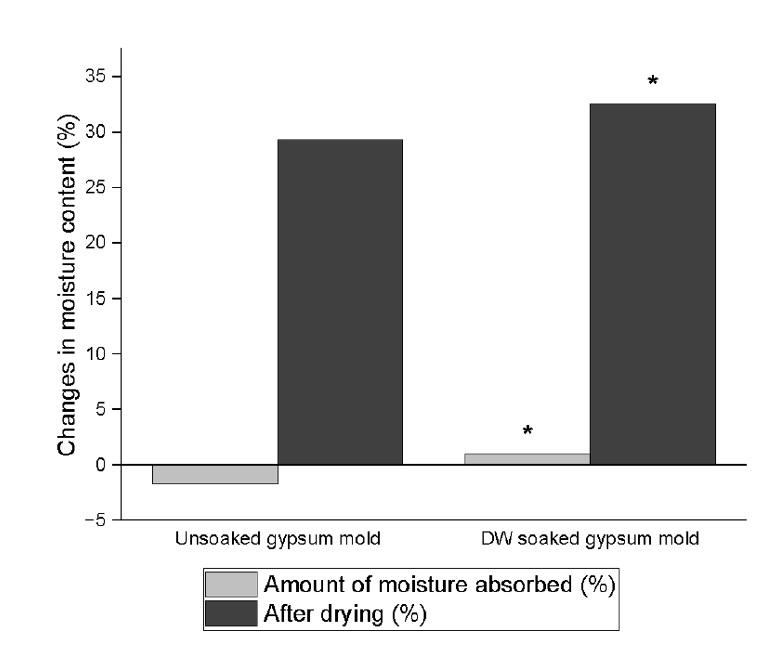

To assess the differences in moisture content between the US and DW-soaked molds, the weight of each mold was measured at three different time points: 1 hour after setting (prior to storage at 100% humidity), after storage, and after drying in a vacuum oven.

Setting time

Setting time was evaluated using Gilmore needles (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA). The initial setting time was defined as the time required for the test cement to solidify sufficiently to withstand a Gilmore needle (113.4 g, tip diameter 2.12 mm). The final setting time was defined as the time required to resist a heavier Gilmore needle (453.6 g, tip diameter 1.06 mm) without significant indentation. The initial and final setting times were monitored at 5-minute intervals, starting 20 minutes before the anticipated setting time based on a pilot study. The time at which the needle no longer indented the sealer surface was recorded. Each specimen was tested three times, and the needle tip was cleaned after each measurement.

Surface microhardness measurement

During incubation, gauze saturated with PBS or HCl was placed on the samples according to their assigned groups. The samples were incubated at 37°C under 100% relative humidity for 3 days. To ensure the maintenance of appropriate pH levels, the gauze pieces were replaced every 12 hours. The DW group with no gauze was used; moisture was maintained by incubation under high relative humidity.

The samples were then ground using 1,200-grit silicon carbide paper and wet-polished with minimal hand pressure to facilitate indentation and minimize preparation effects on surface microhardness. The microhardness was measured using a Vickers microhardness tester (HM-221, Mitutoyo, Tokyo, Japan). Square-based and pyramid-shaped diamond indenters were used, applying a load of 0.1 kgf for both Endoseal MTA and One-Fil, and 1 kgf for Well-Root ST. This adjustment was made according to the pilot test, which revealed that the lower load of 0.1 kgf did not produce visible or reproducible indentations on Well-Root ST samples under our testing conditions. The indentation time was set to 10 seconds at room temperature. Vickers hardness was calculated using the following formula:

where F represents the load in kilograms of force, d is the mean of the two diagonals in millimeters, and HV is the Vickers microhardness. The microhardness values were measured three times and the average values were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Weight changes were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The effects of CSBS type and environmental conditions on the setting time and microhardness were analyzed using Welch’s analysis of variance, followed by the Games-Howell post hoc test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

The differences in the moisture content between the US and DW-soaked molds are presented in

Figure 1. Significantly lower moisture content was observed in US gypsum molds compared with DW-soaked molds after 24 hours at 37°C and 100% relative humidity, as determined by the Mann-Whitney

U-test (

p < 0.001).

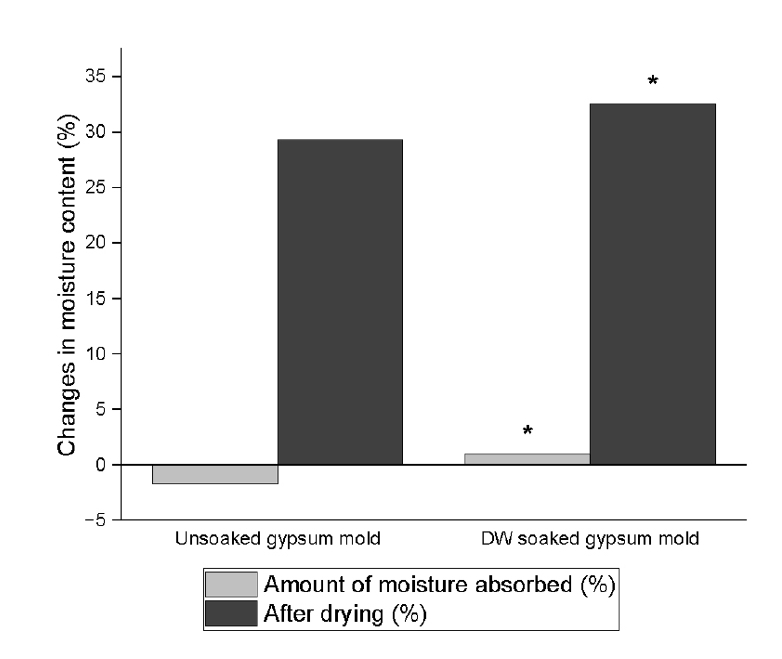

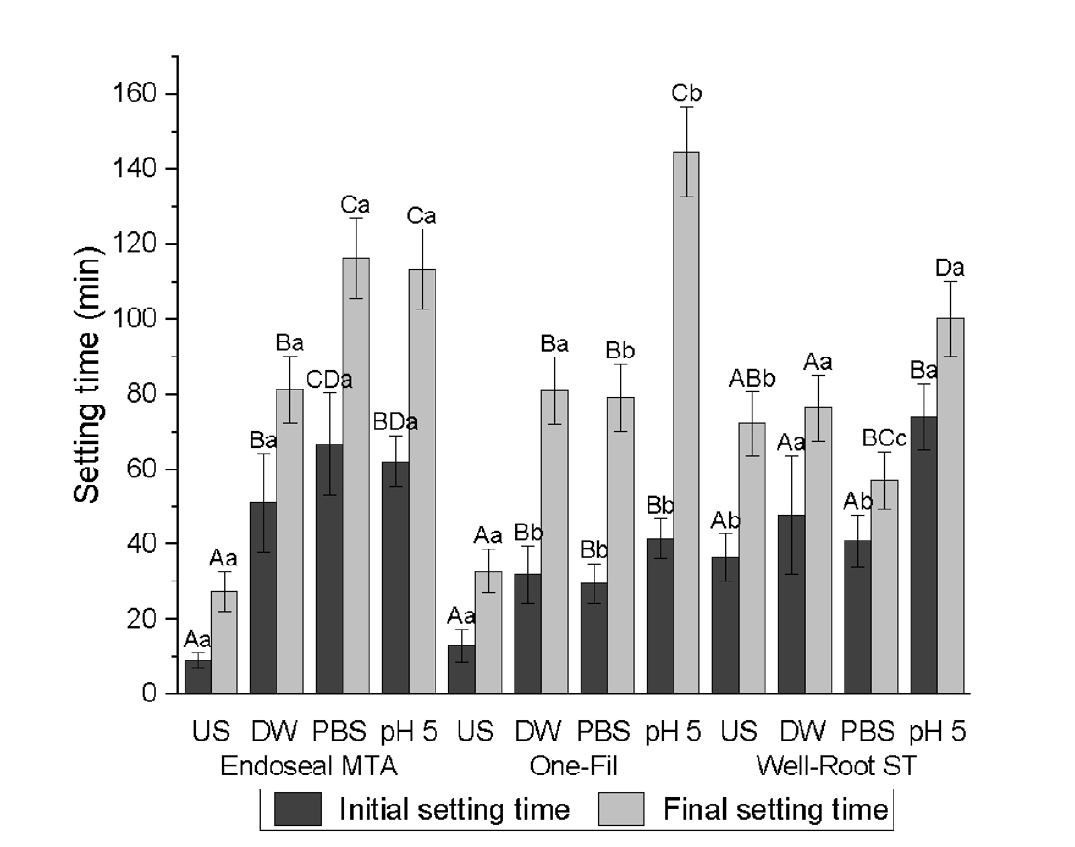

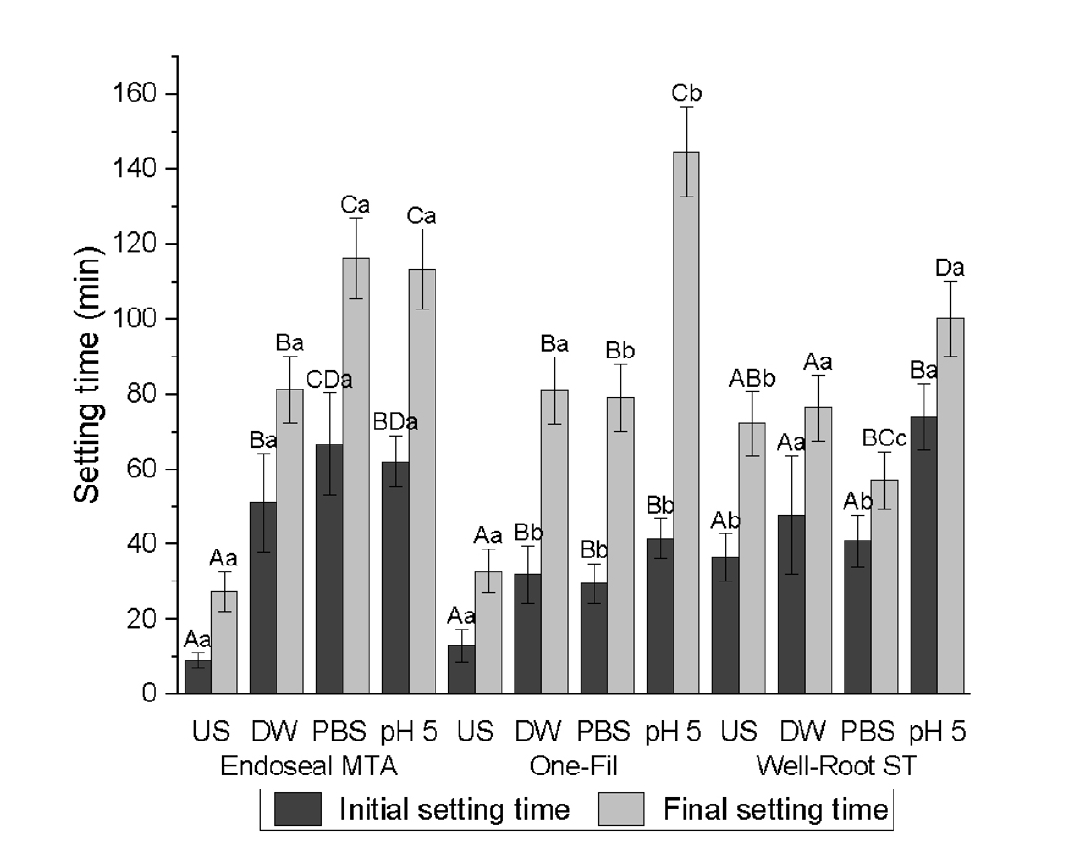

A significant two-way interaction between the CSBS and environmental conditions was observed for both the initial and final setting times (

p < 0.001) (

Tables 3 and

4,

Figure 2). The CSBS type and environmental conditions significantly influenced the initial and final setting times (

p < 0.001). Shorter initial and final setting times were recorded in the US group than in the pH 5 group (

p < 0.001).

For Endoseal MTA, the US group exhibited significantly shorter initial setting times than the soaked group. However, no significant differences were observed between the DW, PBS, and pH 5 conditions. A similar pattern was noted for the final setting time; however, the PBS and pH 5 groups had significantly longer setting times than the DW group.

One-Fil displayed comparable trends, with significantly shorter initial and final setting times in the US group than in the soaked groups. The pH 5 group exhibited a significantly longer initial setting time than the PBS group. The final setting time was markedly prolonged in the pH 5 group, exceeding that of all the other conditions.

For the well-rooted ST, the initial and final setting times for the US, DW, and PBS groups did not differ significantly. However, exposure to the acidic pH 5 solution significantly delayed both the initial and final setting times that to all other groups.

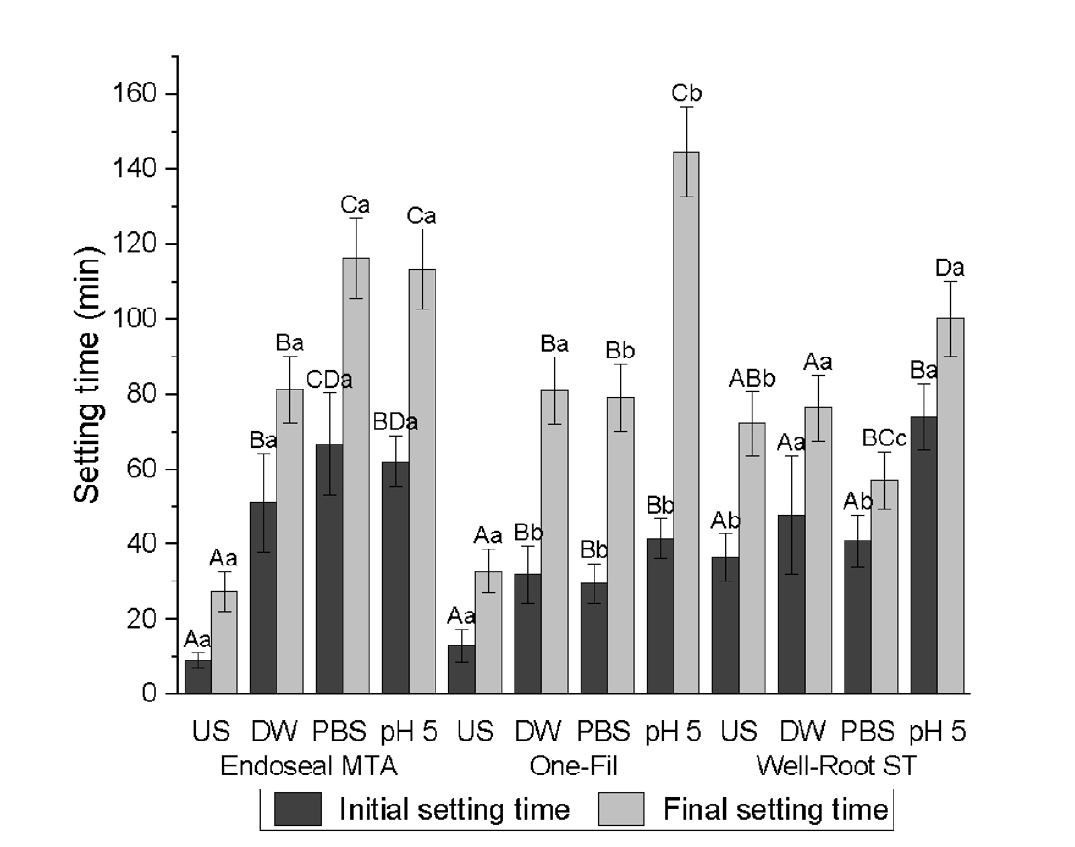

Surface microhardness

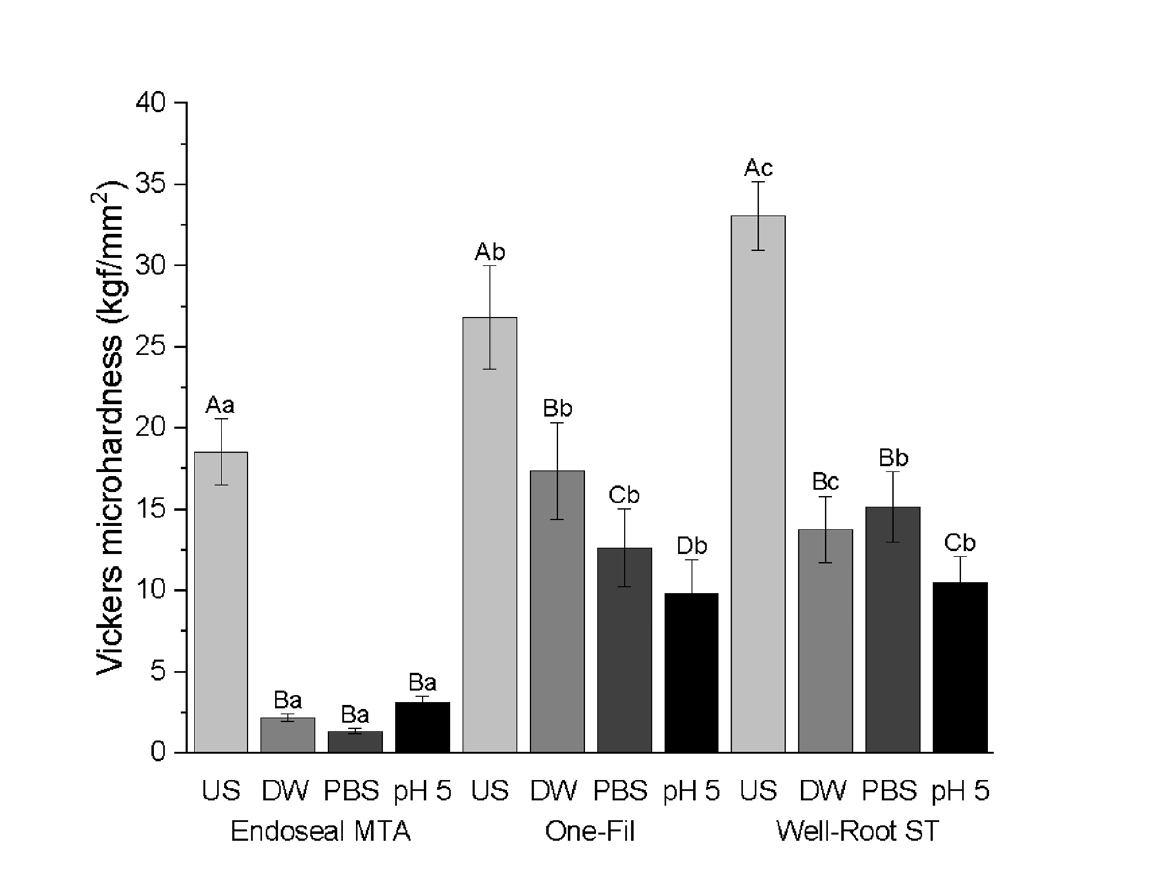

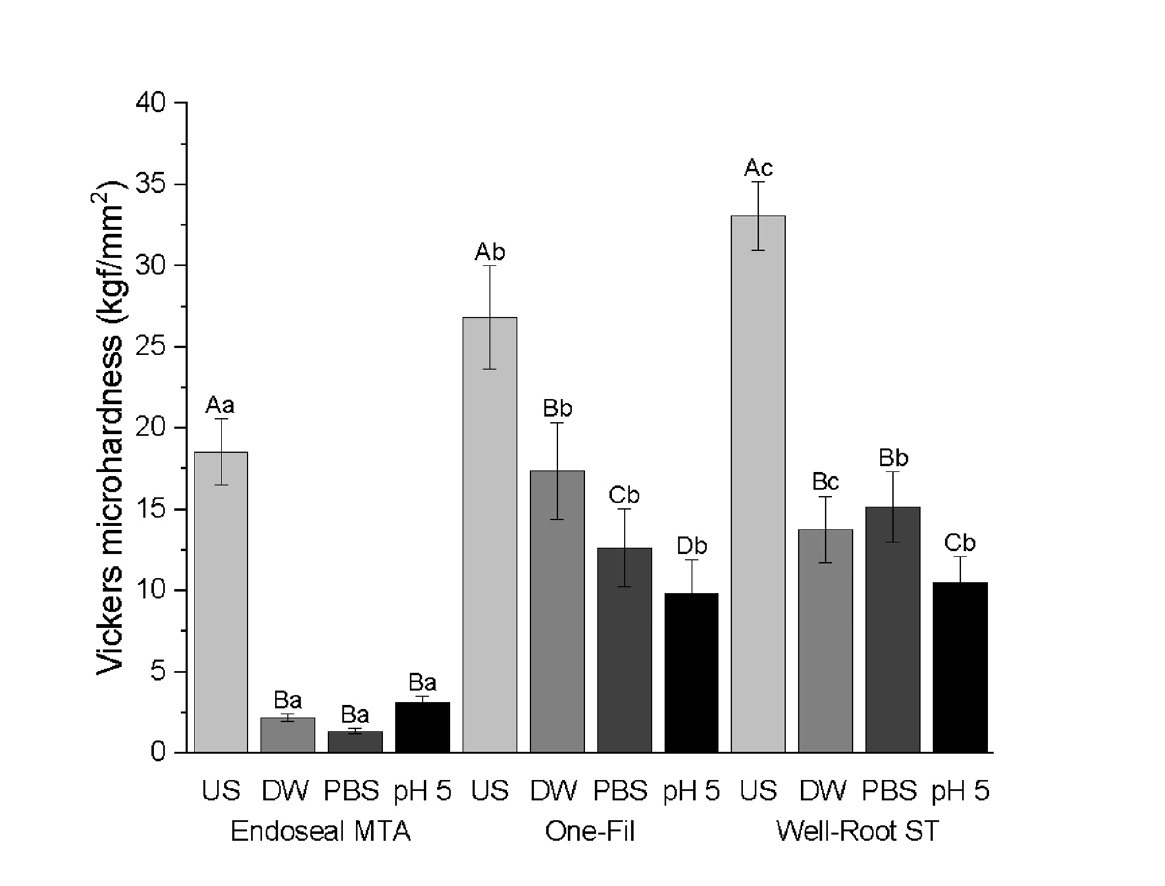

Both CSBS type and environmental conditions significantly affected the microhardness (

p < 0.0001) (

Table 5,

Figure 3). Across all the tested sealers, the US group consistently exhibited significantly higher Vickers microhardness values than the soaked groups (DW, PBS, and pH 5) (

p < 0.0001). Among the soaked groups, PBS exposure resulted in the lowest microhardness in Endoseal MTA, which was significantly lower than that of the DW and pH 5 groups. For One-Fil, the pH 5 group had the lowest value (

p < 0.0001) and that of the PBS group was significantly lower than that of the DW group. For Well-Root ST, the pH 5 group produced the lowest microhardness, whereas the DW and PBS groups exhibited similar microhardness values without significant differences. Across all tested conditions, Endoseal MTA exhibited significantly lower Vickers microhardness values than One-Fil and Well-Root ST (

p < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Advancements in bioceramic technologies have increased the use of CSBSs in endodontics. These sealers have compositions and properties similar to those of MTA, but offer additional benefits, including nonstaining characteristics, reduced impurities, and smaller particle sizes [

4,

19]. Excellent flowability, high pH, good dimensional stability, and adequate radiopacity have been reported for CSBSs

in vitro [

8,

20,

21]. As the properties of root canal sealers significantly influence the quality of root canal fillings and require an adequate setting time [

20], evaluating the setting time and surface microhardness as indicators of the setting process is essential [

15].

In the present study, the setting times and microhardness of three premixed CSBSs were investigated. The CSBSs are hydraulic and require water for initiating the setting process. In the presence of water, calcium silicate reacts to form calcium silicate hydrate gels, leading to the production of calcium hydroxide [

4]. However, the inclusion of water in the sealer significantly increases the initial setting time and decreases the microhardness of CSBSs [

7,

22]. In this study, a significant increase in setting time was observed in the DW group of Endoseal MTA and One-Fil compared with that in the US group. Additionally, all CSBSs demonstrated a significant decrease in the surface microhardness in the DW group compared to that in the US group. Therefore, the second null hypothesis, which states that moisture has no influence on the setting time and microhardness of the CSBSs, was rejected.

Plaster of Paris molds were used to evaluate the setting time and microhardness. Gypsum is known for its irregular shape and porous structure, which enable it to absorb and retain water or moisture [

23]. Because moisture is essential for the setting of calcium silicate-based materials, variations in the moisture content can significantly influence the setting time [

12,

22]. Several previous studies utilized gypsum molds following the ISO 6876 guidelines to assess the setting time and properties of CSBSs [

24,

25]. These studies effectively simulated the moist conditions necessary for sealer hydration, with one study incorporating both

in vivo and

in vitro experiments to replicate periapical tissue environments [

25]. Thus, the present study further combined gypsum molds with controlled PBS and acidic solutions to mimic the chemical conditions of healthy and inflamed periapical tissues more precisely, thereby providing new insights into how these specific ionic and pH variations affect sealer behavior under clinically relevant conditions.

The environmental conditions were regulated through divergence during the storage of the plaster molds. Both the US and soaked molds immersed in different media were used. Moisture content was assessed by measuring the weight changes, which revealed a significant difference between the US and DW-soaked molds. The final setting times of the sealers in the DW group did not vary significantly, whereas those in the PBS group varied significantly among the three sealers. The Vickers microhardness values varied significantly between the US and DW groups for all the tested sealers, leading to rejection of the first null hypothesis.

Nekoofar

et al. [

14] reported that the mean pH of pus from periapical abscesses is typically acidic. Such acidic environments may influence the properties of root canal sealers, which are often exposed to inflamed or infected conditions. Moreover, acidity can affect the structure, hydroxyapatite formation, and antibacterial activity of these materials [

26,

27]. In contrast, healthy blood is slightly alkaline, with a typical pH of 7.4, and PBS is commonly used to simulate tissue fluids containing phosphate [

28]. To mimic the clinical conditions during canal filling, gypsum molds were exposed to two distinct pH conditions to simulate both inflammatory and healthy environments. Significant differences in the initial and final setting times were observed between the PBS and pH 5 groups for One-Fil and Well-Root ST and in microhardness for Endoseal MTA and Well-Root ST, leading to the rejection of the third null hypothesis.

An ideal root canal sealer should have a slow setting time to allow adequate working time. If incompletely set, extrusion of sealers beyond the apical foramen may trigger periapical inflammation [

8,

29]. However, prolonged setting times influenced by formulation and root canal moisture were noted. Setting times have also been found to increase in dry canals [

4,

7].

Microhardness reflects the resistance of a material to deformation under a specified load. Although not included in the ISO standards, it can serve as an indirect measure of material setting [

16]. Microhardness also influences the ease of CSBS removal during non-surgical retreatment [

4]. In this study, all the materials demonstrated significantly higher microhardness in the US group than in the pH 5 group. These findings are consistent with those of previous research that reported significantly lower mean microhardness in both the acidic and PBS groups than in the control [

16].

PBS provides a stable ionic milieu containing phosphate ions and maintains a near-neutral pH through its buffering capacity, which significantly influences the surface reactions of CSBSs. The presence of phosphate ions in PBS promotes the formation and deposition of calcium phosphate compounds such as hydroxyapatite on the surfaces of calcium silicate materials [

30]. This bioactive layer can potentially alter the microhardness values measured on sealer surfaces by creating a mineralized interface that is softer or structurally different from the fully set cement matrix [

10,

30,

31]. Moreover, PBS’s buffering action helps maintain stable pH levels, preventing extreme alkalinity that would typically accelerate the hydration reaction and the formation of calcium silicate hydrate gel, which is an important contributor to the mechanical strength of the set sealer [

30,

32]. Consequently, the microhardness in PBS is affected by both surface calcium phosphate deposition and the modulation of cement hydration kinetics.

Differences in sealer compositions may account for the variations in the setting time and microhardness. In MTA, tricalcium silicate is more reactive, contributing to its initial strength, whereas dicalcium silicate has a more sustained effect over time. Dicalcium silicate cement has also demonstrated strong apatite-forming activity and minimal degradation under acidic conditions [

33]. Endoseal MTA is a premixed type pozzolan-based MTA sealer with dicalcium silicate as its primary component. The use of fine pozzolanic particles allows the premixed material to flow efficiently with the desired working consistency and also reduces the setting time [

34,

35]. However, during the pozzolanic reaction, these cements undergo a gradual reduction in free calcium hydroxide while increasing the formation of stable crystals composed of calcium silicate hydrate and calcium aluminate hydrate. These processes are believed to contribute to the reduced mechanical strength of materials [

36,

37]. This may explain the low microhardness observed in Endoseal MTA under all environmental conditions. Additionally, Well-Root ST contains tricalcium silicate, which is found in both PBS and pH 5 environments [

16]. This could account for the significantly shorter final setting time observed in Well-Root ST than in One-Fil.

Well-Root ST exhibited significantly higher microhardness in the PBS group than in the pH 5 group. Conversely, Endoseal MTA exhibited significantly higher microhardness values in the pH 5 group than in the PBS group. These findings fairly vary from those of previous studies, which reported significantly lower microhardness values for MTA when exposed to an acidic environment compared to solutions with a pH of 7.4 [

32,

37]. However, one study reported no statistically significant difference in the microhardness of Endoseal MTA between PBS and pH 5.4 solutions [

16]. This study further supported their findings using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which revealed predominantly amorphous structures under both conditions, with the acidic group showing fewer planar-like crystals and clusters than the PBS group. Because SEM analysis was not conducted in this study, the underlying microstructural basis remains speculative in the absence of direct microstructural evidence, which is a major limitation of this study.

The microhardness of CSBSs is predominantly influenced by the extent of hydration and formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) phases, which serve as the primary binders imparting strength [

29]. Although a higher calcium silicate content generally correlates with an increased potential for cement hydration and setting, this relationship is complex and is based on the specific phase composition, additives, and particle size distribution. For instance, the presence of calcium aluminates or other supplementary minerals can affect the nucleation and growth of hydrates, thereby affecting microhardness [

30,

38]. Therefore, simple correlations between the calcium silicate content and microhardness should be approached with caution, recognizing that material formulation and environmental interactions critically determine the final mechanical properties.

Despite the valuable insights obtained, a limitation of this study is that it did not fully isolate the individual contributions of pH, moisture content, and the specific chemical nature of the immersion solutions to the observed changes in setting time and microhardness. Previous studies have demonstrated that acidic pH primarily disrupts the hydration and crystallization processes within CSBSs, resulting in delayed setting and reduced microhardness [

15,

16]. Moisture availability is critical for the initiation and progression of hydration reactions. However, excessive moisture can increase porosity and solubility, potentially weakening the cement matrix [

7,

22]. Furthermore, the chemical composition of the immersion media, such as the presence of phosphate ions in PBS, can facilitate apatite or calcium phosphate deposition on the material surface, thereby affecting the microhardness independently of the bulk setting [

29]. Because these factors may interact in complex ways, future studies are warranted to disentangle and quantify their distinct effects on material performance.

Although Silva

et al. [

25] correlated

in vitro and

in vivo setting times using animal models, they primarily focused on biological responses rather than replicating the physicochemical environment of the root canal system. This study investigated the setting characteristics of premixed CSBSs by comparing ISO standards with simulated conditions that mimic the root canal and periapical environments. Clinically, the setting time and microhardness of CSBS may be affected by moisture in the root canal, inflammation, or periapical fluid, potentially affecting the long-term success of root canal therapy. Further studies are warranted to evaluate the clinical performance of CSBS under various environmental conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

The setting environment significantly influenced the setting time and microhardness of the CSBSs. Longer setting times were observed for these sealers when exposed to moisture, PBS, or an acidic environment, except for Well-Root ST, which exhibited prolonged setting times only in acidic environments. Additionally, all three sealers demonstrated reduced microhardness when exposed to moisture, PBS, or acidic environments, compared to the values observed under ISO standard conditions (US group). These findings highlight the importance of environmental factors in CSBS performance, with potential implications for clinical applications.

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author acknowledges MARUCHI (Wonju, Korea), MEDICLUS (Cheongju, Korea), and VERICOM (Chuncheon, Korea) for providing the Endoseal MTA, One-Fil, and Well-Root ST calcium silicate-based root canal sealers, respectively, used in this study.

Figure 1.Moisture content changes of unsoaked and distilled water (DW)-soaked gypsum molds. *p < 0.05, statistically significant.

Figure 2.Initial and final setting times (min) of calcium silicate-based sealers (CSBSs) under different environmental conditions. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) within the same sealer, and different lowercase letters denote significant differences within the same environmental condition. Endoseal MTA: MARUCHI, Wonju, Korea; One-Fil: MEDICLUS, Cheongju, Korea; Well-Root ST: VERICOM, Chuncheon, Korea. US, unsoaked; DW, distilled water; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Figure 3.Vickers microhardness of calcium silicate-based sealers (CSBSs) under different environmental conditions. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) within the same sealer, and different lowercase letters denote significant differences within the same environmental condition. Endoseal MTA: MARUCHI, Wonju, Korea; One-Fil: MEDICLUS, Cheongju, Korea; Well-Root ST: VERICOM, Chuncheon, Korea. US, unsoaked; DW, distilled water; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Table 1.Types and compositions of sealers investigated in this study

|

Sealer |

Manufacturer |

Lot |

Composition |

|

Endoseal MTA |

MARUCHI, Wonju, Korea |

CD231027 |

Calcium silicates (dicalcium silicates), tricalcium aluminates, calcium aluminoferrite, calcium sulfates, zirconium oxide, bismuth trioxide, thickening agent |

|

One-Fil |

MEDICLUS, Cheongju, Korea |

OS41T048 |

Calcium aluminosilicate compound, zirconium oxide, hydrophilic polymer (thickening agent) |

|

Well-Root ST |

VERICOM, Chuncheon, Korea |

WR3D340S |

Calcium silicate compound, calcium sulfate dehydrate, calcium sodium phosphosilicate, zirconium oxide, titanium oxide, thickening agents |

Table 2.Sealers tested under four conditions (unsoaked, distilled Water, PBS, pH 5) with 12 samples per condition

|

Sealer |

Condition |

Sample size (n) |

|

Endoseal MTA |

Unsoaked |

12 |

|

One-Fil |

Distilled water |

12 |

|

Well-Root ST |

PBS (pH 7.4) |

12 |

|

pH 5 (HCl) |

12 |

Table 3.Initial setting time (min) of CSBSs under different environmental conditions

|

Type of CSBS |

Unsoaked |

Distilled water |

PBS |

pH 5 |

|

Endoseal MTA |

9.12 ± 1.97Aa

|

51.20 ± 13.1Ba

|

66.8 ± 13.57CDa

|

62.13 ± 6.92BDa

|

|

One-Fil |

12.93 ± 4.53Aa

|

32 ± 7.47Bb

|

29.65 ± 5.18Bb

|

41.57 ± 5.32Bb

|

|

Well-Root ST |

36.47 ± 6.27Ab

|

47.82 ± 15.75Aa

|

40.8 ± 7.02Ab

|

74.05 ± 8.82Ba

|

Table 4.Final setting time (min) of CSBSs under different environmental conditions

|

Type of CSBS |

Unsoaked |

Distilled water |

PBS |

pH 5 |

|

Endoseal MTA |

27.43 ± 4.68Aa

|

81.28 ± 13.75Ba

|

116.35 ± 12.3Ca

|

113.3 ± 10.38Ca

|

|

One-Fil |

32.93 ± 8.9Aa

|

80.98 ± 21.52Ba

|

79.03 ± 13.88Bb

|

144.63 ± 5.32Cb

|

|

Well-Root ST |

72.32 ± 5.75ABb

|

76.32 ± 16.73Aa

|

57.23 ± 9.75BCc

|

100.28 ± 4.98Da

|

Table 5.Vickers microhardness values (kgf/mm2) of CSBSs under different environmental conditions

|

Type of CSBSs |

Unsoaked |

Distilled water |

PBS |

pH 5 |

|

Endoseal MTA |

18.52 ± 2.04Aa

|

2.2 ± 0.23Ba

|

1.37 ± 0.16Ba

|

3.13 ± 0.42Ba

|

|

One-Fil |

26.81 ± 3.2Ab

|

17.37 ± 2.99Bb

|

12.63 ± 2.39Cb

|

9.8 ± 2.12Db

|

|

Well-Root ST |

33.07 ± 2.09Ac

|

13.78 ± 2.06Bc

|

15.15 ± 2.18Bb

|

10.5 ± 1.59Cb

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Vera J, Siqueira JF, Ricucci D, Loghin S, Fernández N, Flores B, et al. One- versus two-visit endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: a histobacteriologic study. J Endod 2012;38:1040-1052.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Allan NA, Walton RC, Schaeffer MA. Setting times for endodontic sealers under clinical usage and in vitro conditions. J Endod 2001;27:421-423.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Sfeir G, Zogheib C, Patel S, Giraud T, Nagendrababu V, Bukiet F. Calcium silicate-based root canal sealers: a narrative review and clinical perspectives. Materials (Basel) 2021;14:3965.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Hargreaves KM, Berman LH. Cohen’s pathways of the pulp. 11th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier 2016. p. 30.

- 5. Parirokh M, Torabinejad M. Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review: part I: chemical, physical, and antibacterial properties. J Endod 2010;36:16-27.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Torabinejad M, Parirokh M. Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review: part II: leakage and biocompatibility investigations. J Endod 2010;36:190-202.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Xuereb M, Vella P, Damidot D, Sammut CV, Camilleri J. In situ assessment of the setting of tricalcium silicate-based sealers using a dentin pressure model. J Endod 2015;41:111-124.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Park MG, Kim IR, Kim HJ, Kwak SW, Kim HC. Physicochemical properties and cytocompatibility of newly developed calcium silicate-based sealers. Aust Endod J 2021;47:512-519.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Vertuan GC, Duarte MA, Moraes IG, Piazza B, Vasconcelos BC, Alcalde MP, et al. Evaluation of physicochemical properties of a new root canal sealer. J Endod 2018;44:501-505.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Prati C, Gandolfi MG. Calcium silicate bioactive cements: biological perspectives and clinical applications. Dent Mater 2015;31:351-370.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Ferreira CMA, Sassone LM, Gonçalves AS, de Carvalho JJ, Tomás-Catalá CJ, García-Bernal D, et al. Physicochemical, cytotoxicity and in vivo biocompatibility of a high-plasticity calcium-silicate based material. Sci Rep 2019;9:3933.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Koo J, Kwak SW, Kim HC. Differences in setting time of calcium silicate-based sealers under different test conditions. J Dent Sci 2023;18:1042-1046.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Wongkornchaowalit N, Lertchirakarn V. Setting time and flowability of accelerated Portland cement mixed with polycarboxylate superplasticizer. J Endod 2011;37:387-389.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Nekoofar MH, Namazikhah MS, Sheykhrezae MS, Mohammadi MM, Kazemi A, Aseeley Z, et al. PH of pus collected from periapical abscesses. Int Endod J 2009;42:534-538.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Bolhari B, Nekoofar MH, Sharifian M, Ghabrai S, Meraji N, Dummer PM. Acid and microhardness of mineral trioxide aggregate and mineral trioxide aggregate-like materials. J Endod 2014;40:432-435.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Yang DK, Kim S, Park JW, Kim E, Shin SJ. Different setting conditions affect surface characteristics and microhardness of calcium silicate-based sealers. Scanning 2018;2018:7136345.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Qu W, Bai W, Liang YH, Gao XJ. Influence of warm vertical compaction technique on physical properties of root canal sealers. J Endod 2016;42:1829-1833.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Teixeira CG, da Silva MA, Janini AC, de Moura JD, Rocha DG, Pelegrine RA, et al. Setting time of calcium silicate-based sealers at different acidic pHs. G Ital Endod 2023;37:10.32067/GIE.2023.37.01.21.

- 19. Donnermeyer D, Bürklein S, Dammaschke T, Schäfer E. Endodontic sealers based on calcium silicates: a systematic review. Odontology 2019;107:421-436.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 20. Zhou HM, Shen Y, Zheng W, Li L, Zheng YF, Haapasalo M. Physical properties of 5 root canal sealers. J Endod 2013;39:1281-1286.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Candeiro GT, Correia FC, Duarte MA, Ribeiro-Siqueira DC, Gavini G. Evaluation of radiopacity, pH, release of calcium ions, and flow of a bioceramic root canal sealer. J Endod 2012;38:842-845.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Kim HJ, Lee JS, Gwak DH, Ko YS, Lim CI, Lee SY. In vitro comparison of differences in setting time of premixed calcium silicate-based mineral trioxide aggregate according to moisture content of gypsum. Materials (Basel) 2023;17:35.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Jorgensen KD, Kono A. Relationship between the porosity and compressive strength of dental stone. Acta Odontol Scand 1971;29:439-447.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Kim HI, Jang YE, Kim Y, Kim BS. Physicochemical changes in root-canal sealers under thermal challenge: a comparative analysis of calcium silicate- and epoxy-resin-based sealers. Materials (Basel) 2024;17:1932.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Silva EJ, Ehrhardt IC, Sampaio GC, Cardoso ML, Oliveira DD, Uzeda MJ, et al. Determining the setting of root canal sealers using an in vivo animal experimental model. Clin Oral Investig 2021;25:1899-1906.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Hochrein O, Zahn D. On the molecular mechanisms of the acid-induced dissociation of hydroxy-apatite in water. J Mol Model 2011;17:1525-1528.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 27. Bosaid F, Aksel H, Azim AA. Influence of acidic pH on antimicrobial activity of different calcium silicate based-endodontic sealers. Clin Oral Investig 2022;26:5369-5376.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 28. Marques MR, Loebenberg R, Almukainzi M. Simulated biological fluids with possible application in dissolution testing. Dissolution Technol 2011;18:15-28.Article

- 29. Camilleri J. Characterization and hydration kinetics of tricalcium silicate cement for use as a dental biomaterial. Dent Mater 2011;27:836-844.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Gandolfi MG, Ciapetti G, Taddei P, Perut F, Tinti A, Cardoso MV, et al. Apatite formation on bioactive calcium-silicate cements for dentistry affects surface topography and human marrow stromal cells proliferation. Dent Mater 2010;26:974-992.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Jeon MJ, Ahn JS, Park JK, Seo DG. Investigation of the crystal formation from calcium silicate in human dentinal tubules and the effect of phosphate buffer saline concentration. J Dent Sci 2024;19:2278-2285.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Giuliani V, Nieri M, Pace R, Pagavino G. Effects of pH on surface hardness and microstructure of mineral trioxide aggregate and Aureoseal: an in vitro study. J Endod 2010;36:1883-1886.ArticlePubMed

- 33. Han L, Kodama S, Okiji T. Evaluation of calcium-releasing and apatite-forming abilities of fast-setting calcium silicate-based endodontic materials. Int Endod J 2015;48:124-130.ArticlePubMed

- 34. Silva EJ, Carvalho NK, Prado MC, Zanon M, Senna PM, Souza EM, et al. Push-out bond strength of injectable pozzolan-based root canal sealer. J Endod 2016;42:1656-1659.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Turanli L, Uzal B, Bektas F. Effect of material characteristics on the properties of blended cements containing high volumes of natural pozzolans. Cem Concr Res 2004;34:2277-2282.Article

- 36. Rodrıguez-Camacho R, Uribe-Afif R. Importance of using the natural pozzolans on concrete durability. Cem Concr Res 2002;32:1851-1858.Article

- 37. Lee YL, Lee BS, Lin FH, Yun Lin A, Lan WH, Lin CP. Effects of physiological environments on the hydration behavior of mineral trioxide aggregate. Biomaterials 2004;25:787-793.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Camilleri J. Characterization of hydration products of mineral trioxide aggregate. Int Endod J 2008;41:408-417.ArticlePubMed

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite